A Penn State team developed a 3D‑printed hydrogel “skin” that encodes images in its internal structure and reveals them when heated or when the surrounding solvent changes. The method uses halftone‑encoded binary patterns and controlled UV exposure to program regions of the material to respond differently to stimuli, producing a form of 4D printing. The researchers demonstrated the effect with the letters “PSU” and a grayscale Mona Lisa, and say the approach could enable adaptive camouflage and other soft‑material applications, though practical use will require further work on durability and scalability.

Heat‑Activated “Smart Skin” Reveals a Hidden Mona Lisa — A 4D Hydrogel Inspired by Octopus Camouflage

Engineers at Penn State have created a 3D‑printed hydrogel “skin” that can store images in its internal structure and reveal them when exposed to modest changes in temperature or solvent. The work, published in Nature Communications, draws inspiration from cephalopods such as octopuses, which rapidly change color and texture to blend into their surroundings.

The team used a halftone‑encoded printing approach to translate an image into a binary grid of pixels. During 3D printing, controlled ultraviolet (UV) exposure programs subtle differences into regions of the hydrogel rather than adding ink or pigment. These programmed regions respond differently to environmental triggers, making encoded images invisible at room temperature but visible when the material is heated or placed in a different solvent.

Demonstrations and significance. As a proof of concept, the researchers encoded the letters “PSU” and a grayscale reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa into the hydrogel film. Both remained essentially imperceptible at ambient conditions and became clear after a small temperature increase. The authors describe the approach as a form of 4D printing because a three‑dimensional object changes its appearance over time in response to an external stimulus.

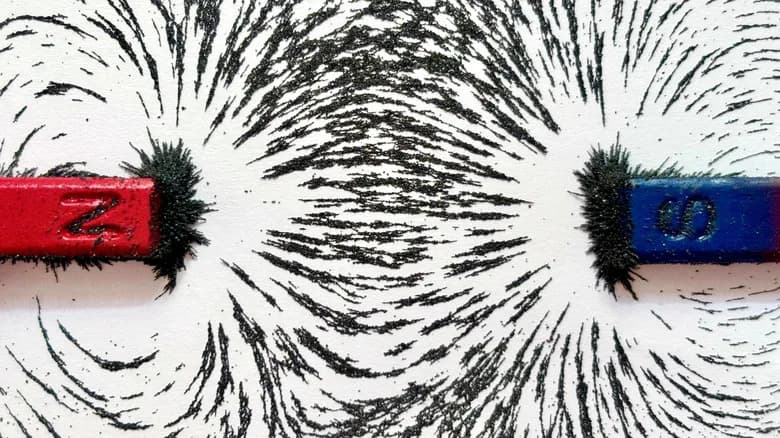

Biological inspiration. Cephalopods achieve rapid camouflage using specialized neuromuscular organs called chromatophores (which change color by expanding and contracting) along with muscular hydrostats that alter skin texture. The Penn State team sought to replicate the combined ability to change appearance and shape within a single soft material.

“This intricate system of nerves and muscles grants soft‑bodied organisms the remarkable ability to simultaneously alter their optical appearance, surface texture, and shape,” the Penn State team writes.

How the encoding works. The halftone encoding converts a desired image into a pattern of 1s and 0s. During printing, UV exposure modulates the hydrogel’s internal network so those regions swell or contract at different rates when heated or exposed to alternate solvents. The differential response increases visual contrast and reveals the hidden pattern. The effect can be tuned by varying pixel patterns, UV dose, and hydrogel chemistry.

Applications and caveats. The researchers suggest the technique could underpin synthetic adaptive camouflage, soft robotics, and other stimuli‑responsive surfaces. The technology is still at an early, laboratory stage: future work must address durability, speed of response, energy efficiency, long‑term stability, and scaling to larger or full‑color images before practical deployment.

Related work. This study builds on earlier bioinspired materials research: for example, Rutgers engineers produced 3D‑printed synthetic muscles that respond to light, and Stanford teams have developed materials that swell under directed electron beams. Roboticists have also built octopus‑like tentacle robots that demonstrate how soft designs can combine movement with surface functions.

Overall, the Penn State hydrogel illustrates how combining biological insight with advanced printing and materials chemistry can produce materials whose appearance is programmed into their structure and revealed by environmental cues.

Help us improve.