Shipwrecks—an estimated three million worldwide—often transform into ecological hotspots where microbes, corals, sponges, fish and sharks establish thriving communities. Microbial biofilms initiate habitat formation on metal and wood, creating conditions for larger organisms and producing biodiversity halos that can extend hundreds of meters. However, wrecks can also harm ecosystems by crushing reefs, releasing long-lived pollutants (detectable up to 80 years later) and helping invasive species spread. Cross-disciplinary research and improved technologies are key to discovering, studying and managing these historical and biological sites.

From Wrecks to Reefs: How Sunken Ships Become Underwater Oases — and Sometimes Hazards

People have sailed the world’s oceans for millennia, but not every voyage ends at a safe harbor. Scientists estimate roughly three million shipwrecks lie across shallow rivers and bays, continental shelves and the deep ocean. Some vessels sank in storms or after running aground; others went down in battles or collisions. While many wrecks evoke human drama and mystery, they also tell a quieter ecological story: sunken ships frequently transform into vibrant, complex habitats.

How a Ship Becomes Habitat

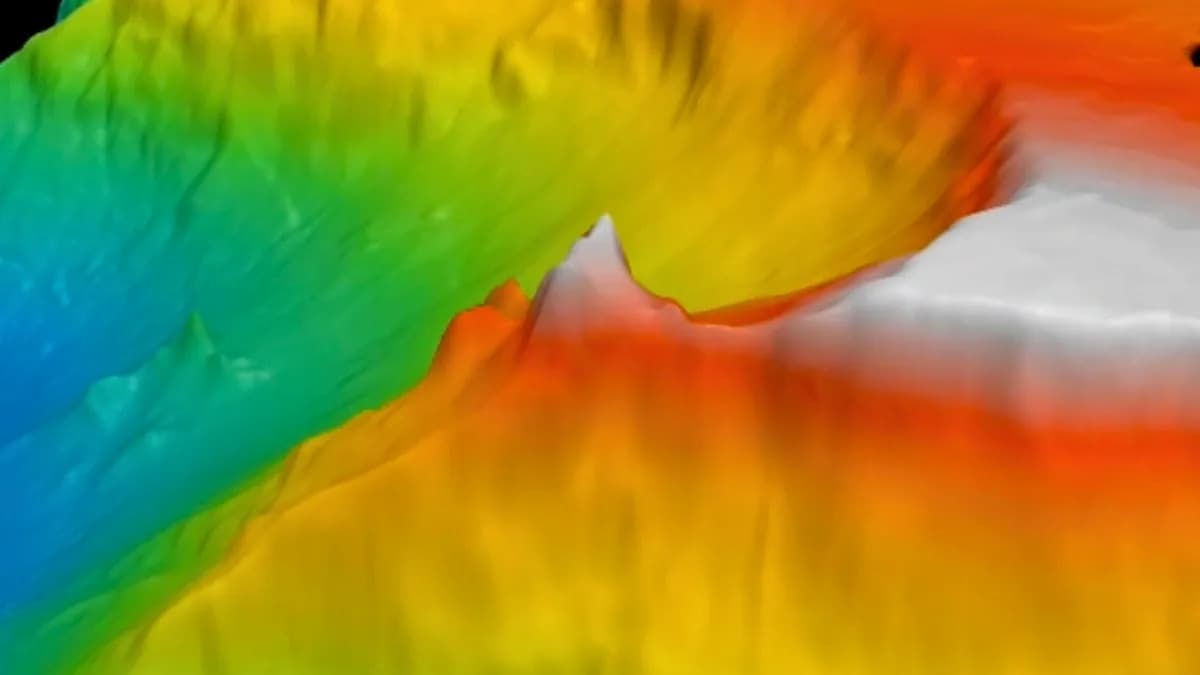

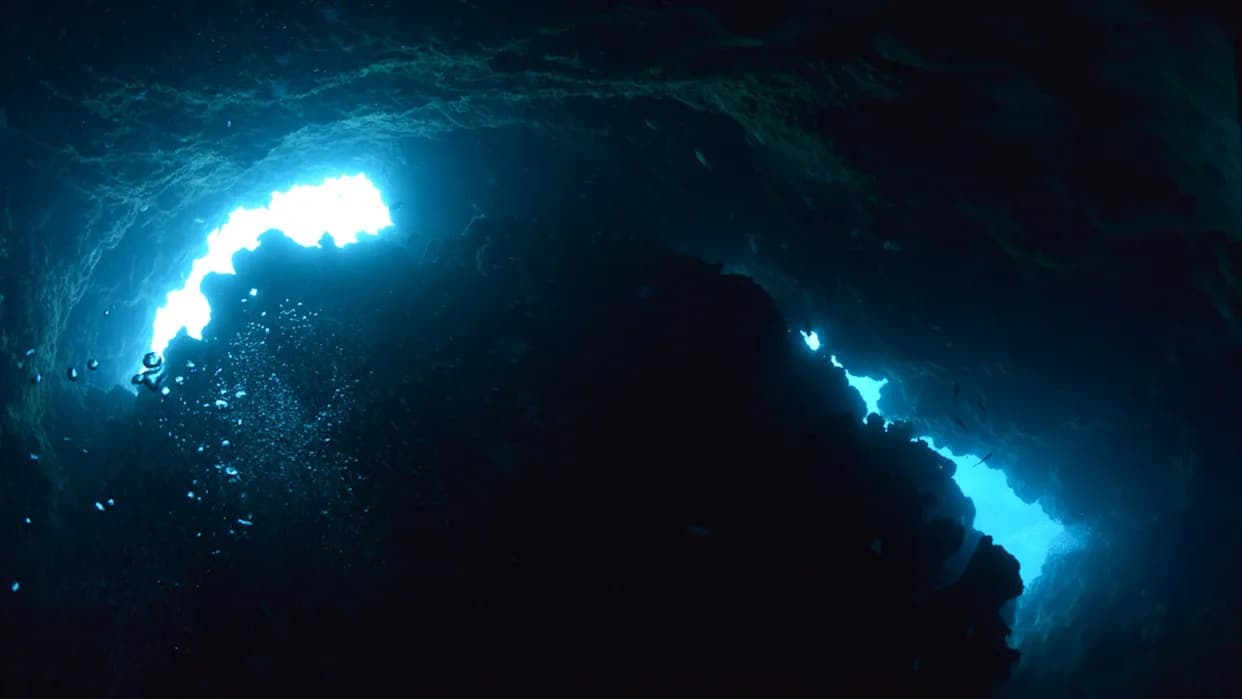

When a vessel sinks, its metal, wood and other materials add three-dimensional structure to otherwise flat seafloors. That structure is rapidly colonized by microscopic organisms. Bacteria and other microbes form a slimy coating called a biofilm, which changes the chemistry and texture of the surface and makes it suitable for larvae of sessile animals like sponges and corals to settle.

Within minutes to days, small fish may shelter in cracks and cavities while larger predators—including sharks—may patrol the structure. Over months and years, corals, sponges, tunicates and diverse invertebrates can create dense, reef-like communities that support fishes and marine mammals.

Examples From the Field

The World War II tanker E.M. Clark, torpedoed off North Carolina in 1942, now rises from a sandy bottom like an ‘‘underwater skyscraper,’’ providing an island of habitat in the sand. In the Gulf of Mexico, the steel luxury yacht Anona supports tube worms that host symbiotic bacteria, generating chemical energy from organic materials on the wreck. Famous wrecks such as the RMS Titanic, RMS Lusitania and the USS Monitor are also sites of notable biological colonization.

Ecological Benefits

Shipwrecks can become local biodiversity hotspots. Microbial communities that modify wreck surfaces often enrich nearby sediments: studies have documented a halo of elevated microbial diversity extending roughly 650–1,000 feet (200–300 meters) from some deep Gulf wrecks. In parts of the Atlantic, thousands of commercially important reef fishes such as grouper concentrate around and inside wrecks. Dense clusters of wrecks—like the ‘‘Graveyard of the Atlantic’’ off North Carolina—can act as stepping stones or corridors that help animals move along the seafloor, for example when fish and sharks migrate or track changing temperatures.

Risks and Downsides

Not all ecological effects are positive. When a wreck lands on an existing reef, it can physically damage corals and alter local nutrient dynamics. For example, an iron shipwreck in the Line Islands introduced iron that promoted algal overgrowth and reduced coral cover. Wrecks may also contain fuel, hazardous cargo or other pollutants; as structures corrode, contaminants can leach into sediments and water. One study found pollutant signals lingering in microbial communities up to 80 years after a sinking.

Wrecks can also facilitate biological invasions by providing new hard substrate where nonnative species can establish and spread. Invasive cup coral has proliferated on World War II wrecks off Brazil, and corallimorph anemones rapidly colonized a wreck at Palmyra Atoll, threatening nearby healthy reefs.

Research, Management, and Conservation

Shipwrecks create millions of natural laboratories for asking questions about succession, connectivity and contaminant persistence in marine ecosystems. A major challenge is that many wrecks remain undiscovered or lie in remote locations. Advances in remote sensing, imaging and autonomous vehicles are improving researchers’ ability to locate and study wreck sites.

Maximizing scientific discovery and managing wrecks responsibly requires collaboration among biologists, archaeologists, engineers and managers. With interdisciplinary research and targeted conservation actions, it is possible to preserve wrecks both as cultural artifacts and as biological resources.

Author: Avery Paxton, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

Help us improve.