Scientists have for the first time filmed ring-like seagrass “fairy circles” off the Outer Hebrides, revealing striking patterns in a habitat that has declined for decades. Historic wasting disease, pollution, dredge fishing and climate-driven stressors all hinder seagrass recovery, though local comebacks have occurred where water quality improved and harmful activities were restricted. Scotland now protects seagrass as a Priority Marine Feature and NatureScot urges urgent mapping to guide restoration and safeguard this carbon-rich coastal habitat.

First Footage of Scotland’s Mysterious Seagrass “Fairy Circles” — And Why They Might Disappear

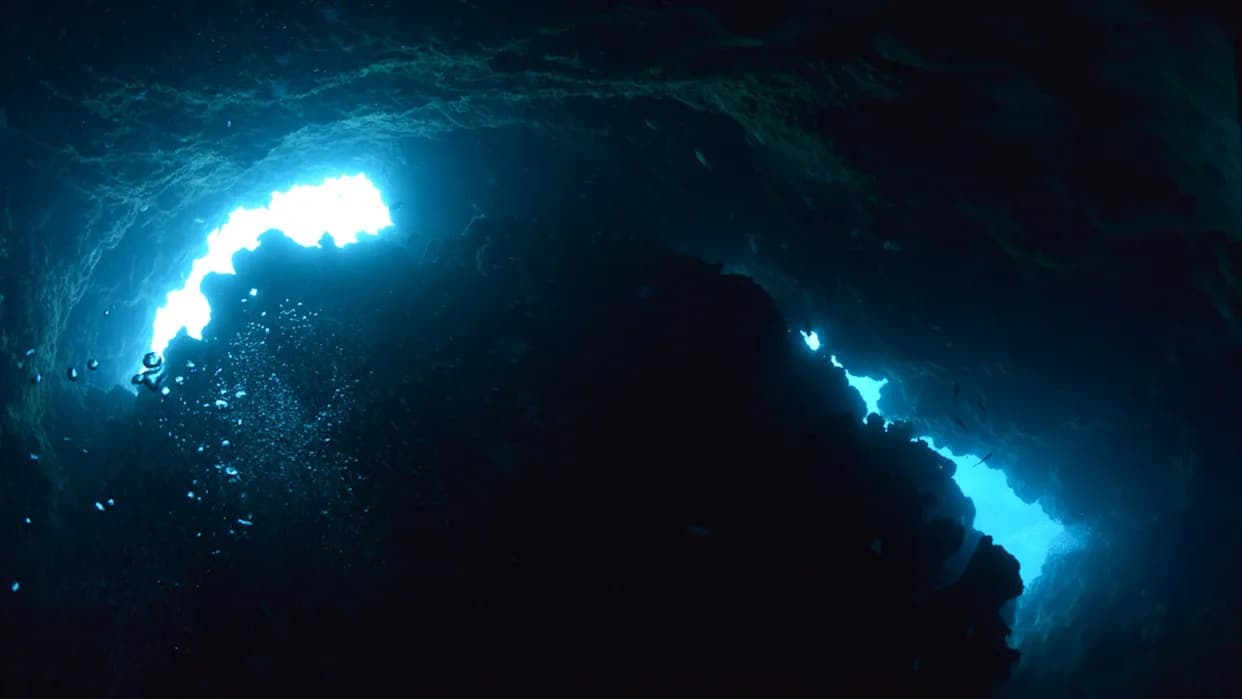

For the first time, scientists have captured video of enigmatic ring-like seagrass formations — nicknamed “fairy circles” by locals — off the Outer Hebrides. The aerial footage, taken by Scotland’s nature agency NatureScot, reveals otherworldly patterns that have long been observed but never filmed, and highlights a fragile habitat facing multiple threats.

Ancient Resource, Modern Crisis

Seagrass once carpeted Scotland’s coasts. Dried beds of Zostera marina and Zostera noltii were historically described as “submarine meadows” or “savannahs of the sea” and were widely used by coastal communities for mattress stuffing, upholstery, fertilizer and thatch. Over the past century, however, these meadows have dramatically declined.

Diseases, Pollution and Other Pressures

In the 1930s a wasting disease linked to the pathogen Labyrinthula macrocystis devastated large areas of Scottish seagrass; beds never fully recovered. Further outbreaks in the 1980s, combined with growing environmental pressures such as nutrient pollution from commercial fish farms and damaging fishing methods, have made natural recovery difficult.

Seagrass now faces a complex mix of threats: ongoing pollution, dredge fishing, invasive seaweeds like Sargassum muticum, and climate-driven stressors. Warming waters, stagnant conditions, hypersalinity, low oxygen and the buildup of hydrogen sulphide in sediments can all weaken plants and create conditions in which pathogens thrive.

Signs of Recovery Where People Act

Conservation measures are showing positive results in places where damaging activities have been restricted and water quality improved. Z. noltii has begun to regrow at Loch Ryan, Loch Indaal and parts of the Firth of Forth, and both Z. marina and Z. noltii have rebounded in Solway Firth after dredging stopped. In some areas dredging and other harmful practices are now limited.

“Seagrass beds are of high conservation value and perform many beneficial physical functions, including reducing tidal energy and coastal erosion, stabilizing coastal sediments, aiding the establishment and protection of saltmarshes, and improving water quality,” NatureScot researchers wrote in a recent report.

Why Seagrass Matters

Seagrass meadows do more than support wildlife: they are excellent carbon sinks, capturing CO2 through photosynthesis and storing carbon in plant tissue and sediments. They provide nursery habitat for marine life, sustain diverse estuarine communities, offer food for migrating geese, and even host specialist species such as certain pipefish.

Policy, Protection and Next Steps

Scotland has designated seagrass beds as a Priority Marine Feature (PMF), meaning developments and other marine uses are allowed only where PMFs will not be harmed. The Water Environment and Water Services Act (2023) strengthens efforts to protect and restore water bodies, with seagrass seen as a key indicator of coastal ecosystem health.

NatureScot calls for an urgent, comprehensive survey of seagrass distribution around the Scottish coast to establish up-to-date baselines, better understand vulnerabilities, and guide restoration and protection efforts.

What We Still Don’t Know

Despite the striking footage, the exact processes that create the ring-like “fairy circles” remain unclear. Further study of these patterns could shed light on local ecological processes and help prioritize sites for conservation and restoration.

Help us improve.