Scientists catalogued 402 bright linear streaks (lineae) on Mercury after analyzing ~100,000 MESSENGER images with machine learning. The streaks cluster on sun-facing crater slopes and often originate near bright depressions called hollows, suggesting volatile-driven outgassing. Because similar features erode quickly elsewhere, the authors conclude these marks may be forming today—implying present-day geological activity. Upcoming observations from the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission should confirm whether the streaks are actively changing.

402 Bright Streaks on Mercury Hint the Tiny Planet Is Still Geologically Active

Mercury—the Solar System's smallest planet—may be far less "dead" than long assumed. A new survey has identified 402 bright linear streaks, known as lineae, and the distribution and context of these features suggest ongoing near-surface activity driven by volatile release.

What the Study Found

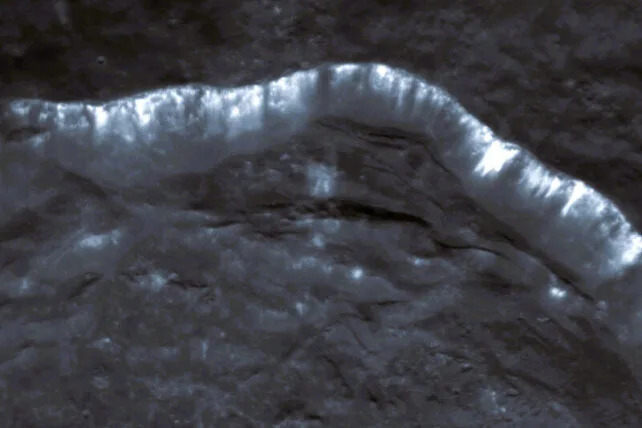

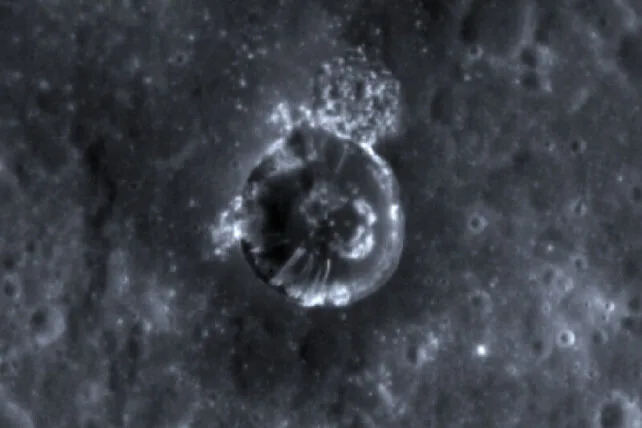

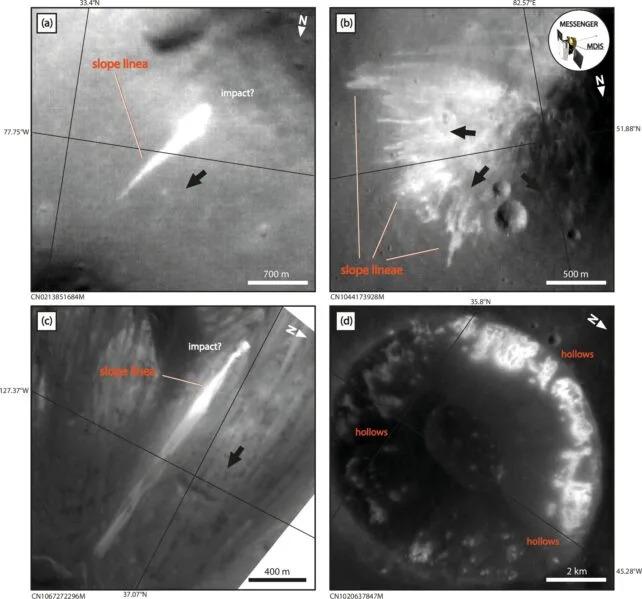

Researchers led by Valentin Bickel (University of Bern, Switzerland) and colleagues at the Astronomical Observatory of Padova (Italy) used machine learning to examine roughly 100,000 high-resolution images taken between 2011 and 2015 by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft. Their catalog of 402 lineae shows these streaks tend to cluster on sun-facing crater slopes and frequently occur near bright depressions called hollows.

Interpretation

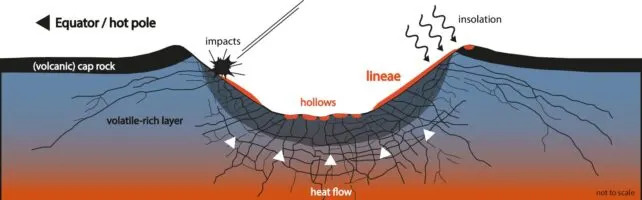

Because similar streaks on other worlds are thought to erode quickly when exposed, the authors argue that Mercury's lineae are likely still forming or evolving today rather than being relics of a long-ago past. The favored explanation is that volatile materials—sulfur is a leading candidate—migrate upward through fractures created by impacts, outgas at or near the surface, and alter surface deposits to form bright streaks.

"Volatile material could reach the surface from deeper layers through networks of cracks in the rock caused by the preceding impact," explains Valentin Bickel. "Most of the streaks appear to originate from bright depressions, so-called 'hollows.' These hollows are probably also formed by the outgassing of volatile material and are usually located in the shallow interior or along the edges of large impact craters."

Why This Matters

Mercury is small, airless, and has cooled for roughly 4.5 billion years, so evidence for active near-surface processes would change our picture of its geological evolution. If volatiles are migrating and modifying the surface now, Mercury's near-surface environment is more dynamic than previously thought.

Next Steps

The team plans to test their hypothesis using fresh observations from ongoing and upcoming missions—most notably ESA and JAXA's joint BepiColombo mission, which will provide new, higher-resolution views of Mercury. If the lineae are actively forming or fading on human timescales, BepiColombo should detect changes compared with the MESSENGER-era images.

The study appears in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Help us improve.