The Corpus Christi jury acquitted Adrian Gonzales of 29 child endangerment counts tied to the 2022 Uvalde school shooting, highlighting the legal challenge of criminalizing omissions by police officers. Prosecutors relied on an atypical application of Article 22.041(c) and cited duties in Articles 6.06 and 6.05 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. The defense argued Gonzales never saw the shooter, that prevention may not have been within his power, and that the chaotic scene created reasonable doubt. The verdict echoes the Parkland case and underscores how statutory language and the requirement of a specific duty limit criminal liability for inaction in chaotic shootings.

Why the Uvalde Officer’s Acquittal Highlights the Legal Limits of Criminalizing Police Inaction

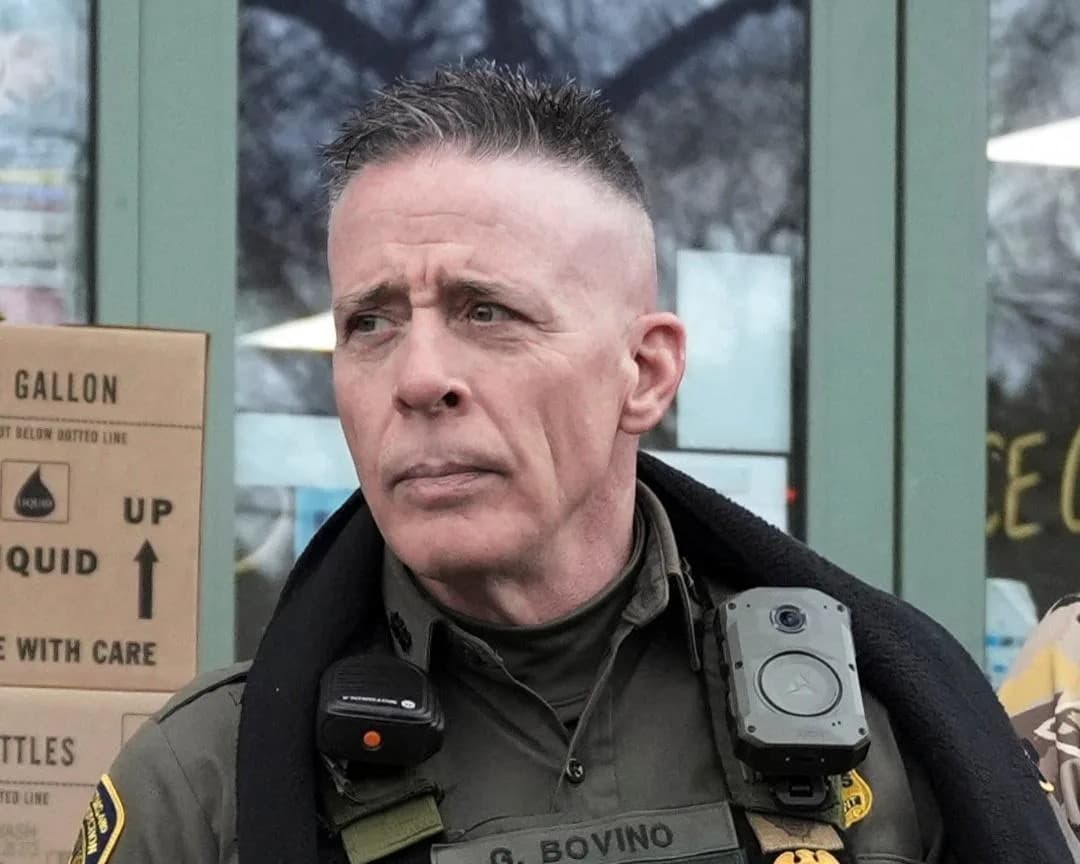

Adrian Gonzales, the first officer to arrive at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, during the 2022 mass shooting that killed 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers, was acquitted this week of 29 counts of child endangerment. The verdict, returned by a Corpus Christi jury after roughly seven hours of deliberation, underscores how difficult it is to convert alleged failures to stop a mass shooter into criminal liability under current Texas law.

The 29 counts corresponded to the 19 children who were killed and 10 who survived. Prosecutors argued Gonzales knew the assailant’s location before the attacker entered classrooms and that his alleged inaction amounted to 29 state jail felonies—each carrying a maximum sentence of two years. Their case relied on an unusual application of Article 22.041(c) of the Texas Penal Code, a provision most commonly used to prosecute parents or caregivers who place children in imminent danger by act or omission.

Article 22.041(c) makes criminal conduct that "intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence, by act or omission, places a child" in imminent danger of death or serious injury. But Texas law generally requires a specific legal duty to act for an omission to be criminalized. To establish such a duty, prosecutors cited Article 6.06 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure (an officer’s duty to prevent an offense occurring "in the presence of a peace officer, or within his view") and Article 6.05 (an officer’s duty to prevent a threatened injury if it is within his power).

Defense, Prosecution, and the Legal Question of Duty

In closing, defense attorney Jason Goss told jurors that Gonzales never actually "saw the shooter" and therefore was not literally "in the presence of the shooter," a key phrase in Article 6.06. Special prosecutor Bill Turner argued the opposite: Gonzales should be treated as having been in the shooter’s presence because he failed to pursue, confront, or impede the attacker. The dispute boiled down to statutory interpretation: do these provisions require an officer to seek out a threat, or only to act when the threat is plainly present and within the officer’s power to stop?

The defense also argued that even if a duty existed, prosecutors had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that it was "within his power" to prevent the killings and that Gonzales acted with the requisite mental state—intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence. The defense stressed chaotic conditions at the scene, the speed and confusion of the attack, and the presence of other officers who were not prosecuted.

Broader Context and Legal Implications

Observers and lawyers have noted the similarity to the Scot Peterson case after the 2018 Parkland shooting, in which jurors also acquitted the officer accused of failing to intervene. Both prosecutions depended on creative readings of statutes that were not originally aimed at policing omissions. The Uvalde case further highlights the tension between holding individuals accountable for professional failures and the high legal bar for turning omissions into criminal offenses.

Critics argue that Gonzales was singled out amid broader systemic failures that contributed to a 77-minute delay before the shooter was confronted and killed by a U.S. Border Patrol Tactical Unit. Supporters of the prosecution say accountability for on-scene decisions matters; defenders warn that criminalizing split-second choices could deter officers from acting in future crises. The jury’s verdict ultimately reflects jurors’ reluctance to extend criminal liability to an officer’s omissions under the statutes at issue, even while many continue to criticize the overall police response in Uvalde.

Gonzales was suspended along with other members of the school district police department and had left his position by early 2023. Professional discipline and public scrutiny can follow serious failures, but this case illustrates that not all grave professional lapses meet the legal standard for criminal punishment.

Help us improve.