More than a decade after a deadly Boko Haram attack, thousands of displaced residents have returned to Malam Fatori under a government resettlement programme. Returnees face persistent ISWAP threats nearby, heavy military controls, long waits at checkpoints and restricted access to farmland and fishing grounds. Basic services are strained — food prices have risen, clinics and schools are understaffed and malnutrition is a concern — yet community farming, cooperatives and rebuilding efforts offer cautious hope.

Rebuilding Under Fire: Returnees Reclaim Malam Fatori Amid ISWAP Threats and Military Controls

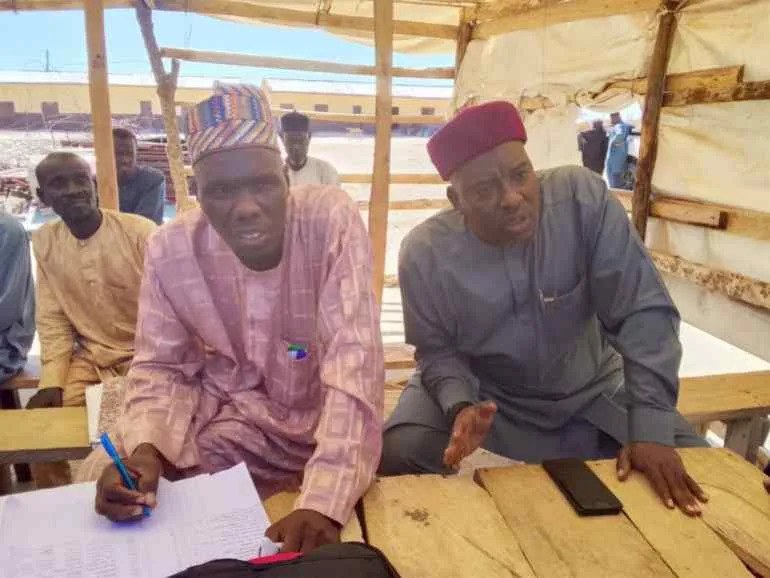

Malam Fatori, Nigeria — More than a decade after a brutal Boko Haram attack that killed four of his children, 65-year-old farmer Isa Aji Mohammed has returned to the parched fields around his Lake Chad village to try to rebuild his life.

Isa and thousands of other former residents returned last year under a government resettlement programme. Once a productive agricultural market town near the border with Niger, Malam Fatori today bears the visible scars of conflict: roofless mud-brick houses, cracked walls, overgrown fields and clogged irrigation channels slowly being cleared by hand.

Security Presence and Daily Restrictions

Armed patrols, checkpoints and observation posts line main routes and public spaces. Families report frequent security checks, movement curbs and curfews that residents accept as necessary but say also disrupt farming, market activity and access to neighbouring communities. Farmers may wait up to eight hours at military checkpoints to move produce, and movement beyond town limits often requires military permits or armed escorts.

Authorities say the town is under heavy protection, yet fighters from the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) are believed to shelter in swampy ground roughly two kilometres from Malam Fatori, using difficult terrain as cover. Surrounding areas continue to suffer attacks, kidnappings and harassment along farming tracks and access roads, creating a fragile environment for returnees.

Livelihoods, Food Security And Services

Before the violence, families in Malam Fatori cultivated extensive fields and harvested hundreds of bags of rice, maize and beans. Today many returnees cultivate much smaller plots, constrained by insecurity, lack of tools, seed shortages and limited water. Community farming initiatives and small cooperatives — where women weave mats and process groundnut oil — are helping to restore local production.

Food prices have risen sharply: a kilogram of rice now sells for about 1,200 naira (roughly $0.83), nearly double previous prices, and fish from Lake Chad have become scarce and expensive because of restricted access. Most families now eat only twice a day, and aid deliveries are irregular and quickly exhausted.

Basic services remain strained. The town clinic, staffed by six nurses, ration vaccines, malaria treatment and maternal care amid power outages and equipment shortages. Malam Fatori Central Primary School has only 10 functional classrooms for hundreds of pupils; some lessons take place outdoors and teacher shortages persist. In some cases soldiers step in to teach basic civic lessons, a stopgap that reassures parents but is no substitute for trained educators.

Protection Concerns And Humanitarian Standards

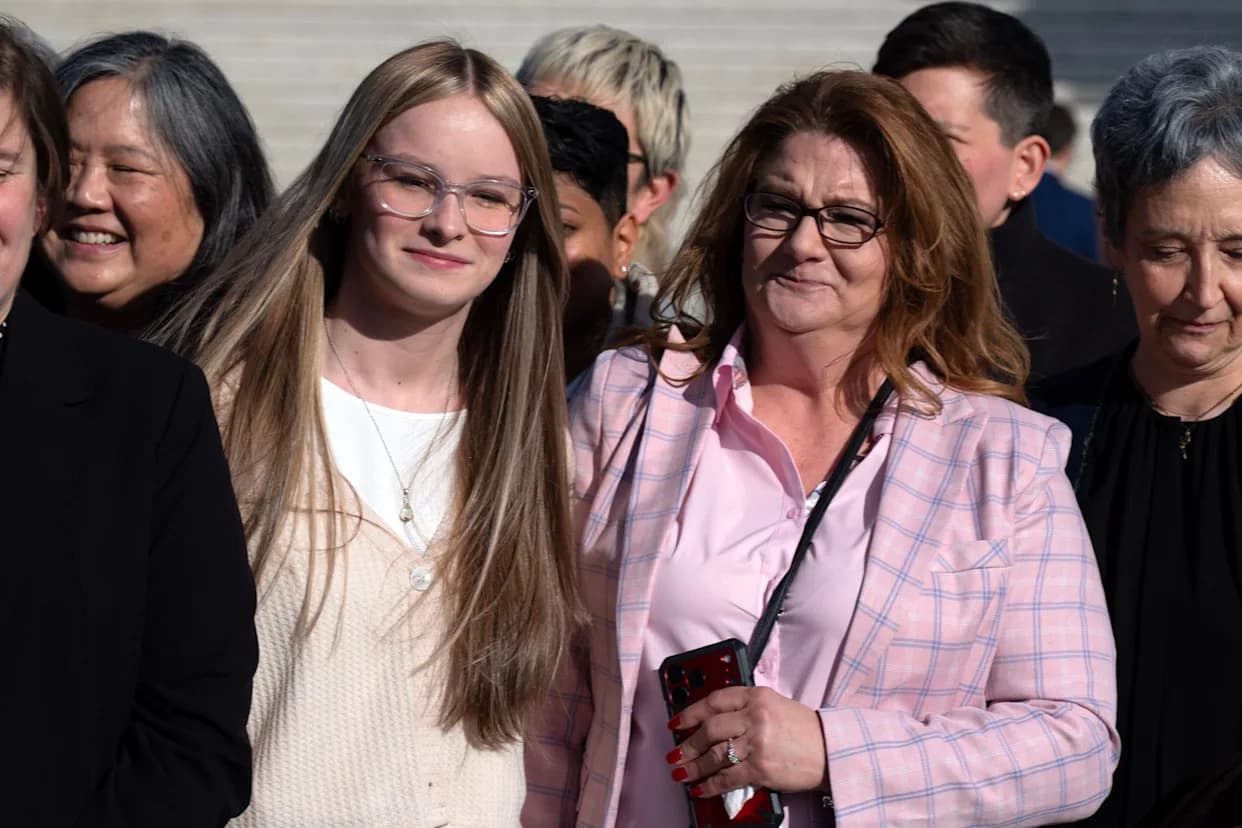

The United Nations has urged caution, warning that returns must be voluntary, informed, safe, dignified and sustainable. Mohamed Malick, the UN resident and humanitarian coordinator in Nigeria, said returns to insecure areas such as Malam Fatori should be carefully evaluated against established safety and humanitarian standards and should proceed only when essential services and livelihoods are possible.

Lives Between Fear And Belonging

Despite the risks, many residents say they returned out of belonging and necessity. "We are caught between fear and order," Isa said. "But still, we must live. Still, we must plant. Still, we must hope." Former fighters who entered a government deradicalisation and repentance programme now sometimes assist in protecting farmers, while local bricklayers and community volunteers work to rebuild homes from locally sourced materials.

For families such as Bulama Shettima’s — who lost two sons to ISWAP and later had one son deradicalised — returning is part of a broader effort to heal, rebuild and invest in children’s education as a pathway out of violence. The town's slow recovery combines resilience and fragility: collective action and basic services persist, but long-term recovery depends on security, humanitarian access and sustainable livelihoods.

Published in collaboration with Egab.

Help us improve.