The Earth has two norths: the Geographic North Pole (true north) and the Magnetic North Pole, which compasses and many devices use. Motion in Earth’s molten outer core generates the magnetic field, causing the Magnetic North Pole to wander. Historically it drifted slowly across northern Canada but accelerated around 1990 to roughly 34 miles per year. Navigators correct for the difference using local declination, while smartphones use magnetometers and the World Magnetic Model for automatic corrections.

Why the North Pole Moves — What That Means for Santa, Your Compass and Your Phone

After delivering gifts on Christmas Eve, Santa still needs to find his way back to the North Pole — even in whiteout conditions when the reindeer can barely see. A compass might help, but which “north” should he follow?

There are two different North Poles. The Geographic (or true) North Pole marks the top of Earth’s axis of rotation and is the point shown on maps. The Magnetic North Pole is the point toward which a compass needle points. These two poles do not occupy the same location, and the magnetic pole moves over time.

Why Magnetic North Wanders

The Magnetic North Pole drifts because Earth’s interior is dynamic. Far beneath our feet the inner core and outer core behave differently: the inner core is solid, while the outer core is molten and made mostly of iron and nickel. The inner core begins about 5,150 km (roughly 3,200 miles) below the surface.

Heat and convection in the outer core cause the liquid metal to flow. Those flows generate and modify Earth’s magnetic field in a process called the geodynamo. As patterns of flow change, the magnetic field shifts and the Magnetic North Pole wanders.

A Recent Increase in Speed

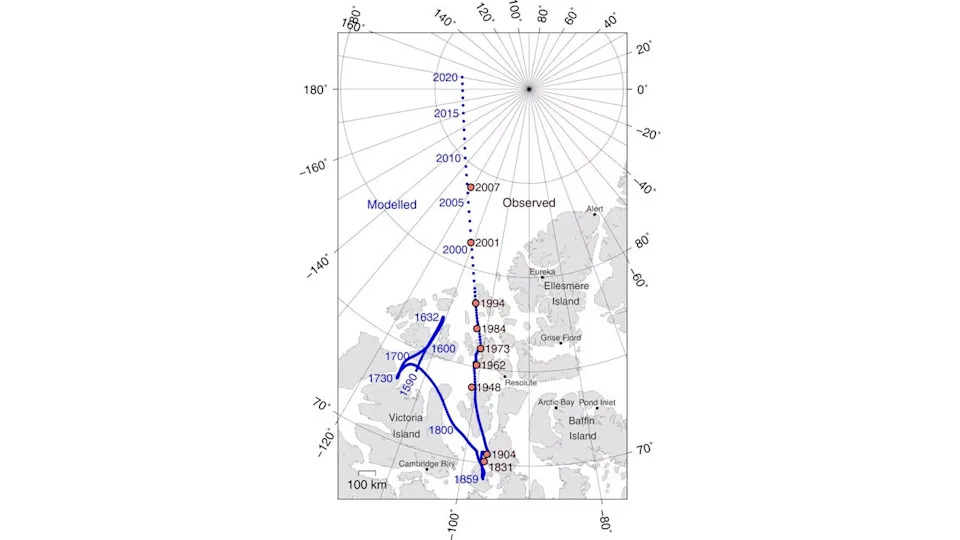

For several centuries the Magnetic North Pole moved relatively slowly over northern Canada — roughly 6–9 miles (10–15 km) per year. Around 1990 its drift accelerated and in recent decades it has reached speeds up to about 34 miles (55 km) per year. Scientists link this change to altered flow patterns in the outer core, though the exact drivers remain an active area of research.

What This Means for Navigation

Whether Santa uses a traditional compass or a smartphone, both reference magnetic north when determining heading. GPS can give a precise location, but it does not inherently provide heading without a reference orientation.

If you use a magnetic compass, you must correct for local magnetic declination — the angle between true north and magnetic north — to plot an accurate course. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other agencies provide online calculators and maps of declination.

Smartphones and modern navigation devices use built-in magnetometers and the World Magnetic Model to measure the local magnetic field and apply corrections automatically, so they can provide accurate headings even as the magnetic pole moves.

So whether Santa relies on instruments, modern tech, or the reindeer’s instinct, the wandering Magnetic North Pole is a factor in how anyone navigates toward the ice-covered Geographic North Pole — and back home again.

Scott Brame, Research Assistant Professor of Earth Science, Clemson University