The Earth has two North Poles: the geographic (true) north that marks the planet's rotation axis, and the magnetic north that a compass points toward. The magnetic pole wanders because flows of molten iron in Earth’s outer core generate the planet’s magnetic field. Its drift was slow for centuries (about 6–9 miles per year) but accelerated around 1990 to as much as ~34 miles per year. For navigation, compasses require a declination correction (NOAA provides a calculator), while smartphones use a magnetometer and the World Magnetic Model to adjust headings automatically.

Why the North Pole Keeps Moving — What It Means for Santa, Your Compass, and GPS

After delivering presents on Christmas Eve, Santa still needs to find his way back to the North Pole — even when blowing snow makes navigation difficult for his reindeer. A compass could help, but which "North Pole" should he follow?

There are two different North Poles: the geographic North Pole (true north), which marks one end of Earth's axis of rotation, and the magnetic North Pole, the direction a compass needle points. They are not in the same place, and the magnetic pole wanders over time.

One way to picture the geographic pole is to hold a tennis ball with your right thumb at the bottom and your middle finger at the top, then spin it with your left hand. The thumb and middle-finger contact points define an axis of rotation that passes through the center of the ball — that axis intersects the globe at the geographic North and South poles.

Why Magnetic North Moves

The magnetic North Pole moves because Earth has an active, dynamic interior. About 3,200 miles below the surface the inner core is solid, but it is surrounded by a molten outer core of liquid iron and nickel. Heat-driven flows in that liquid metal generate electric currents, which produce the planet's magnetic field — a process called the geodynamo.

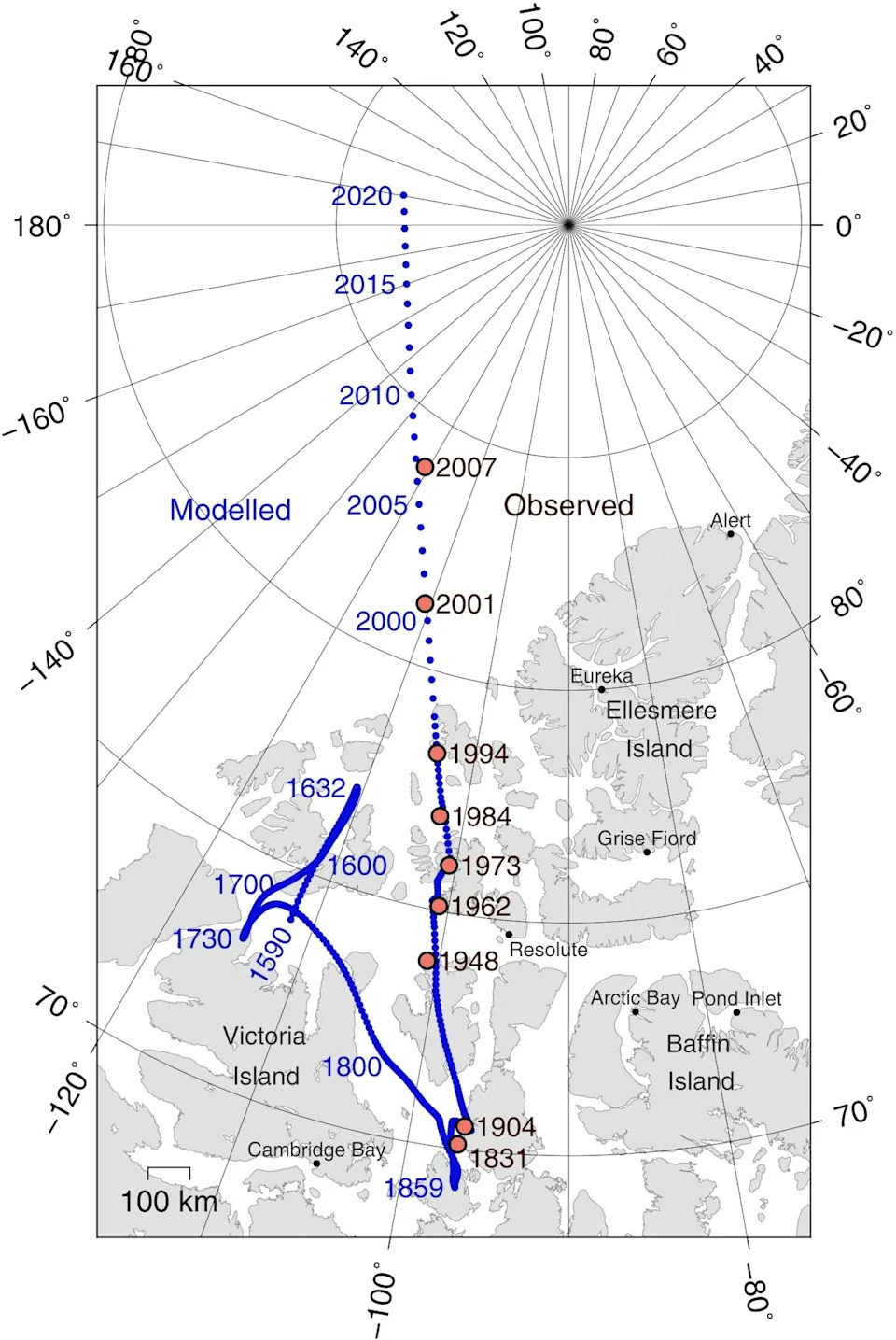

As flows in the outer core change, the magnetic field shifts and the magnetic pole wanders. For roughly the past 600 years the magnetic pole drifted slowly across northern Canada at about 6–9 miles (10–15 km) per year. Around 1990 its speed increased markedly — in recent decades it has moved as fast as about 34 miles (55 km) per year and shifted generally toward the geographic North Pole.

What This Means for Navigation

Compasses point toward magnetic north, not true north. To convert a compass bearing into a direction toward the geographic North Pole (or any true-heading destination), navigators must apply a declination correction — the angular difference between magnetic north and true north at a particular location. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides an online declination calculator to help mariners and hikers.

Modern smartphones and navigation devices include small magnetometers that measure the local magnetic field. They use the World Magnetic Model (WMM) and location data (from GPS) to automatically correct headings so the device can present an accurate direction relative to true north.

So whether Santa uses an old-fashioned compass and adjusts for declination, relies on a phone that applies the World Magnetic Model, or simply trusts his reindeer, magnetic north plays a central role in finding the way home.

In short: Two North Poles exist; the magnetic pole wanders because of movements in Earth’s molten outer core; compasses need a declination correction and modern devices compensate using the World Magnetic Model.

This article is adapted from The Conversation. Original author: Scott Brame, Clemson University. Scott Brame reports no relevant conflicts of interest beyond their academic appointment.