The Arab Spring began in Tunisia after Mohamed Bouazizi’s 2010 protest and sparked uprisings across the region that toppled or weakened long‑standing leaders. Ben Ali fled and later died in exile; Mubarak resigned, faced trials and died after his release; Gaddafi and Saleh were killed amid conflict. Syria’s uprising became a protracted civil war; as of mid‑2024 Bashar al‑Assad remained in power, while the country continued to suffer widespread destruction and displacement.

Where the Arab Spring’s Toppled Leaders Are Now — A 15‑Year Retrospective

Fifteen years after Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26‑year‑old Tunisian street vendor, set himself on fire to protest police harassment, the Arab world witnessed a cascade of uprisings in 2010–2011 that became known as the Arab Spring. The movement toppled or weakened several long‑standing regimes, but outcomes varied widely — from exile and prosecutions to violent deaths and prolonged civil war.

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1936–2019)

In Power: 1987–2011 (23 years) — Status: Died In Exile

Ben Ali became Tunisia’s leader in 1987 after declaring his predecessor medically unfit. His rule relied on tight security control, a loyal ruling party and limited political freedoms. Economic liberalisation brought growth for some but also entrenched corruption and inequality. Following Mohamed Bouazizi’s self‑immolation on December 17, 2010, mass protests forced Ben Ali to flee to Saudi Arabia on January 14, 2011. He was later sentenced in absentia by Tunisian courts and died in Jeddah in September 2019.

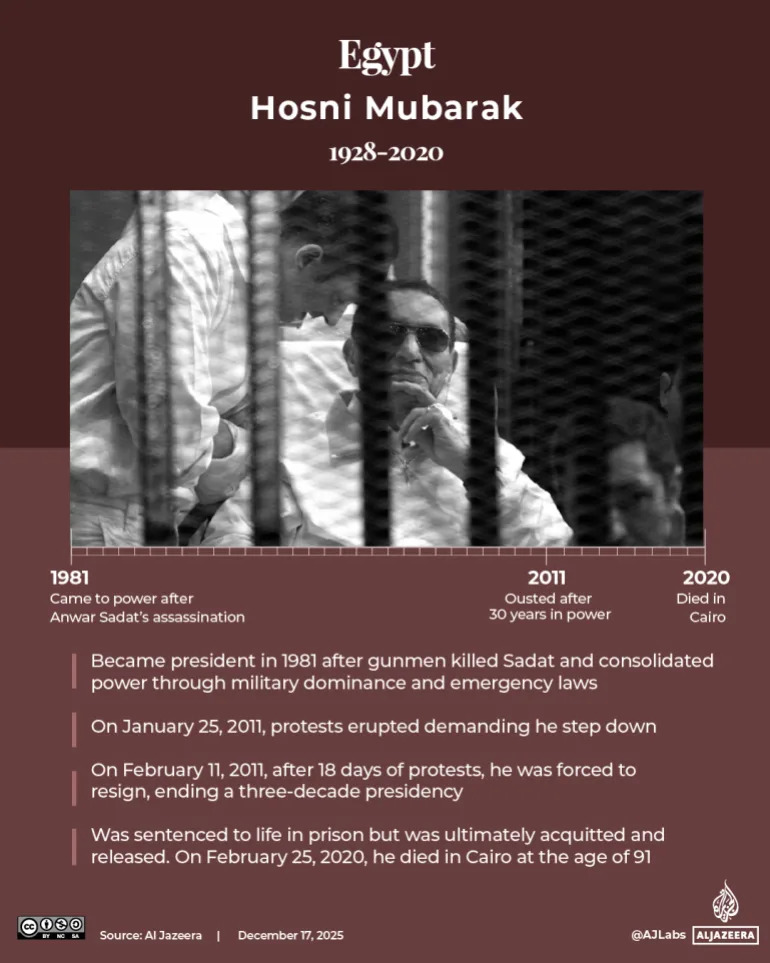

Hosni Mubarak (1928–2020)

In Power: 1981–2011 (30 years) — Status: Died In Egypt (After Release)

Mubarak, an air force veteran, led Egypt after Anwar Sadat’s assassination in 1981. His presidency was marked by prolonged emergency powers, military influence and limited political space. On January 25, 2011, widespread protests erupted; Mubarak resigned on February 11, 2011. He faced trials over the deaths of protesters and corruption charges; after lengthy legal proceedings and periods of detention, he was acquitted and released in 2017. Mubarak died in Cairo in February 2020.

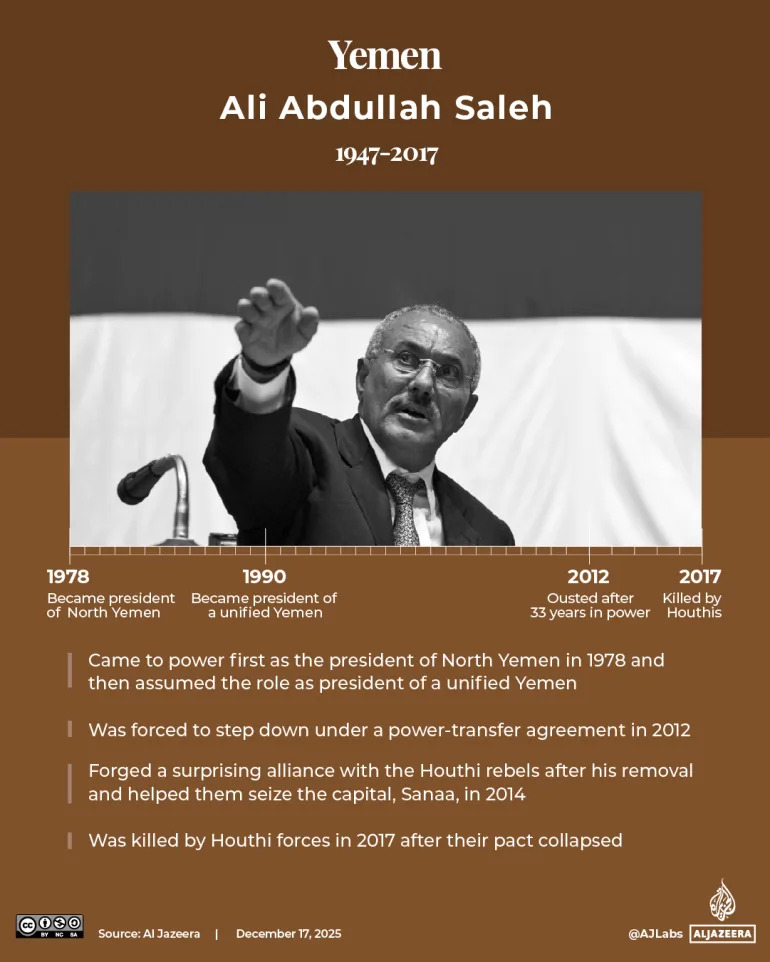

Ali Abdullah Saleh (1947–2017)

In Power: 1978–2012 (33 years) — Status: Killed In Conflict

Saleh ruled North Yemen from 1978 and the unified Republic of Yemen from 1990. Skilled in tribal and factional politics, he survived repeated crises but was driven from office by mass protests and a 2012 power‑transfer agreement. He later allied with the Houthi movement, contributing to Yemen’s wider conflict; after breaking with the Houthis in 2017 he was killed amid fighting in December 2017.

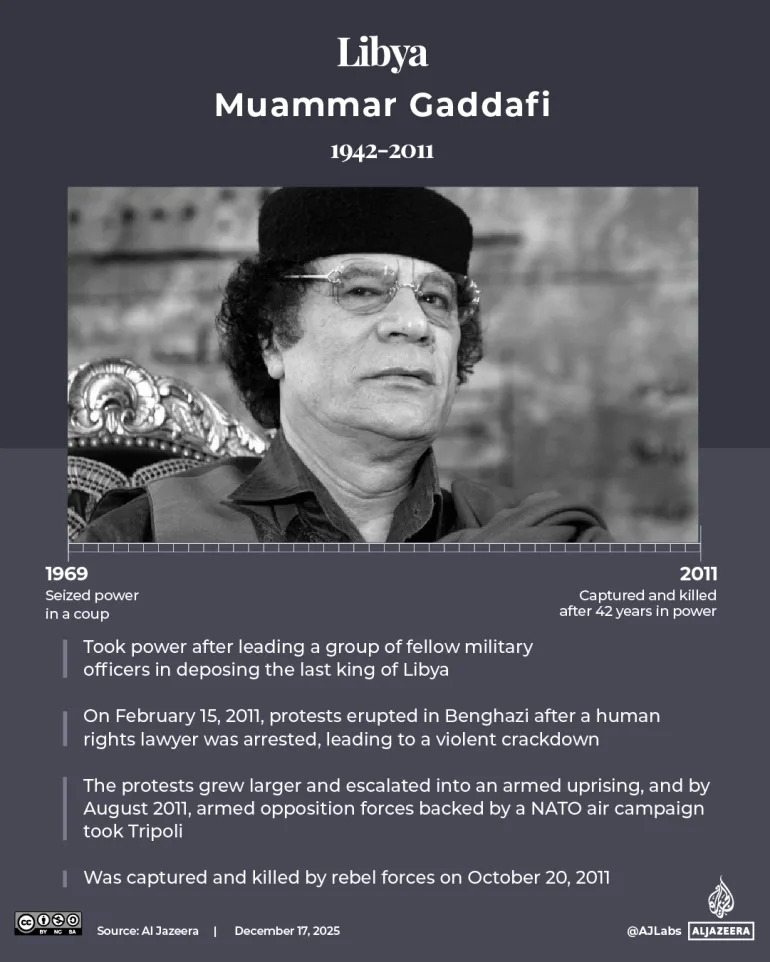

Muammar Gaddafi (1942–2011)

In Power: 1969–2011 (42 years) — Status: Killed By Rebel Forces

Gaddafi seized power in a 1969 coup and ruled Libya through a personalised system that relied on revolutionary committees and control of oil wealth. International isolation eased in the 2000s after he abandoned certain weapons programs, but his violent suppression of 2011 protests escalated into civil war. With NATO air support and internal defections, rebels captured Tripoli by August; Gaddafi was captured and killed in Sirte on October 20, 2011.

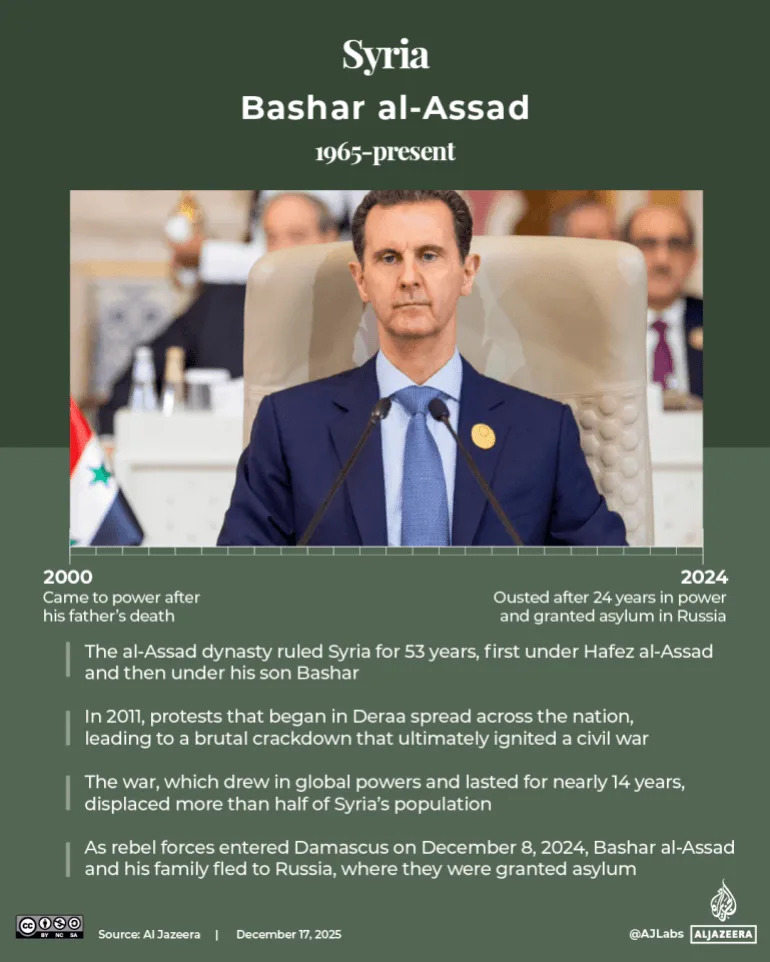

Bashar al‑Assad (1965– )

In Power: 2000–Present (as of mid‑2024) — Status: In Power; Country Ravaged By Civil War

Bashar al‑Assad succeeded his father in 2000 after a rapid constitutional change. The 2011 protests in Deraa evolved into a devastating civil war after a harsh government crackdown. The conflict drew in regional and global powers, displaced millions and produced a major humanitarian crisis. As of mid‑2024 Assad retained control of major population centres with support from allies, while large parts of Syria remained contested, occupied or under different de‑facto authorities.

Aftermath And Legacy

The Arab Spring’s immediate effect — the removal or weakening of several long‑time leaders — was just the start. Across the region the uprisings led to a mix of democratic openings, authoritarian backsliding, violent power struggles and prolonged humanitarian emergencies. The movement reshaped politics, popular expectations and geopolitics, but its long‑term outcomes remain mixed and contested.

Help us improve.