Researchers led by Kiel University found exceptionally high concentrations of microplastics and microrubber in the seafloor sediments of Illa Grossa’s bay, averaging 1,514 particles/kg and reaching more than 6,300 in one sample. Over 90% of particles were under 250 micrometers, small enough to be ingested by the endangered reef-building coral Cladocora caespitosa. The study highlights that even legally protected marine reserves are vulnerable to distant sources of pollution, compounding threats from heatwaves and toxic fly ash and jeopardizing local fisheries and coastal protection.

Remote Protected Mediterranean Reef Smothered by Microplastics and Microrubber, Scientists Warn

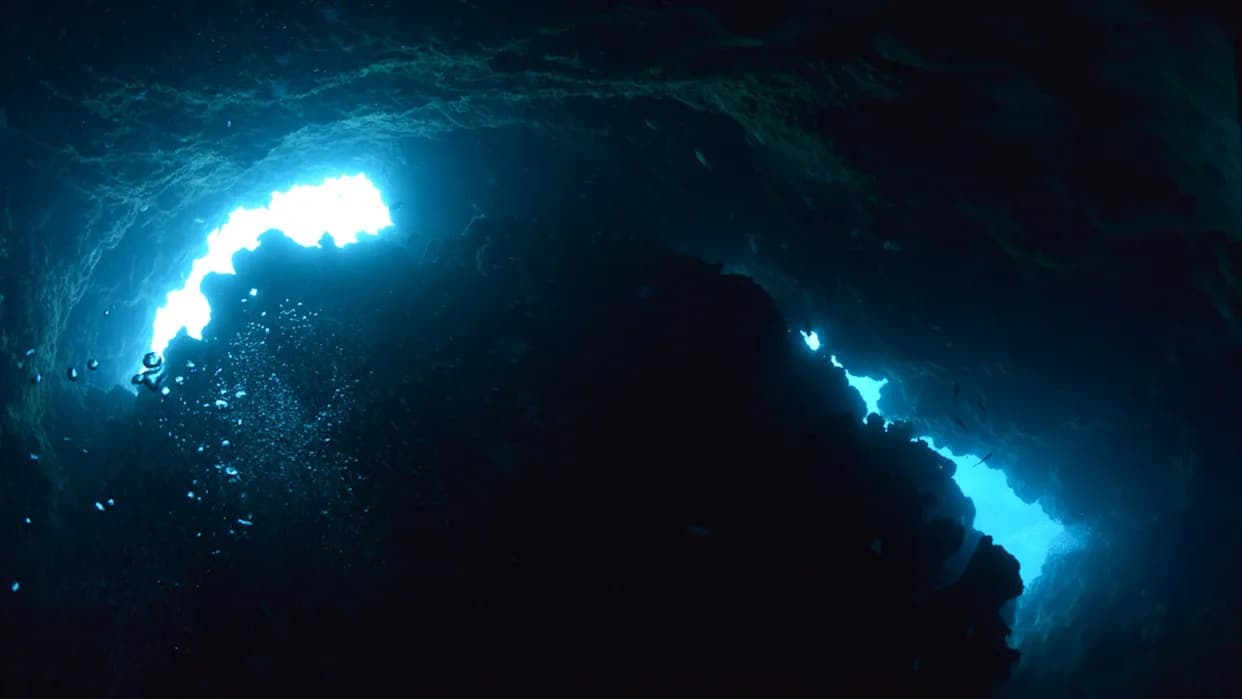

Scientists surveying the bay of Illa Grossa, a protected island about 34 miles off Spain’s coast in the Columbretes Islands marine reserve, have found alarming concentrations of microplastics and microrubber in the seafloor sediment surrounding the Mediterranean’s only reef-building coral, Cladocora caespitosa.

A research team led by Kiel University and reporting in Marine Pollution Bulletin collected five sediment samples from the bay and identified a pollution hotspot. The seafloor contained an average of 1,514 microplastic and microrubber particles per kilogram of sediment, and one sample exceeded 6,300 particles. More than 90% of those particles were smaller than 250 micrometers — sizes that researchers say are easily ingested by corals and other small marine organisms.

What was found and why it matters

Microplastics are tiny fragments produced as larger plastic items break down. Microrubber, primarily generated by tyre wear and other rubber sources, is increasingly detected in marine environments. Because both are microscopic, they can be taken up by corals and filter feeders, potentially interfering with feeding, growth and reproduction. The long-term ecological and health consequences for animals and humans are an area of active research.

“Our findings are deeply concerning,” said Dr. Lars Reuning, the study’s lead author. He noted that although the measurements cover a limited area, they demonstrate that even legally protected marine areas are not immune to global plastic pollution, placing sensitive coral species at risk.

Compounding threats

The bay has also faced other stressors: researchers previously detected fly ash — a toxic byproduct of coal combustion — in these waters, and studies have documented declines in C. caespitosa tied to rising sea temperatures and recurrent marine heatwaves. The combined impact of pollutants, warming and other pressures reduces coral resilience and undermines the reef’s ability to support associated fish, sea urchins, sponges and other marine life.

Local and coastal consequences

Healthy coral structures provide habitat and help sustain local fisheries, supporting food and livelihoods for coastal communities. Coral reefs also buffer shorelines from wave energy; losing reef structure can increase coastal erosion and flood risk for nearby communities.

Why Illa Grossa is affected

The researchers observed that the bay’s location makes it a sink for debris carried by the Northern Current, concentrating trapped waste in this protected area despite the lack of local pollution sources.

What can be done

Addressing this threat requires action at multiple levels: reducing single-use plastics, improving capture of stormwater and runoff, limiting tyre and road-wear emissions, and stronger waste-management policies to prevent debris from entering waterways. Researchers are also testing restoration tools — from acoustic playback that encourages reef-building to targeted removal of invasive species with underwater robots — but reducing pollution is essential to give vulnerable corals a chance to recover.

Protecting remote reefs like Illa Grossa calls for both local stewardship and international commitments to cut plastic pollution and greenhouse-gas emissions that drive marine heatwaves.

Help us improve.