New modelling reveals that 'marine snow' — tiny, sticky organic aggregates — captures fragmented plastics and carries them into the deep ocean via the biological pump. The model helps explain the discrepancy between estimated plastic inputs and what is observed at the surface. Researchers warn that microplastics in deep-sea sediments could affect carbon sequestration and ecosystem health, and they urge lifecycle solutions to prevent plastics entering marine systems.

Marine Snow Sinks Plastics: New Model Explains the Ocean’s 'Missing' Pollution

New study shows tiny 'marine snow' particles drag plastics into the deep ocean

Overview: A new modelling study reported by ScienceAlert and published via Royal Society Publishing suggests much of the plastic that seems to be “missing” from the ocean surface is actually being transported to the deep sea by the same biological processes that move carbon and nutrients downward.

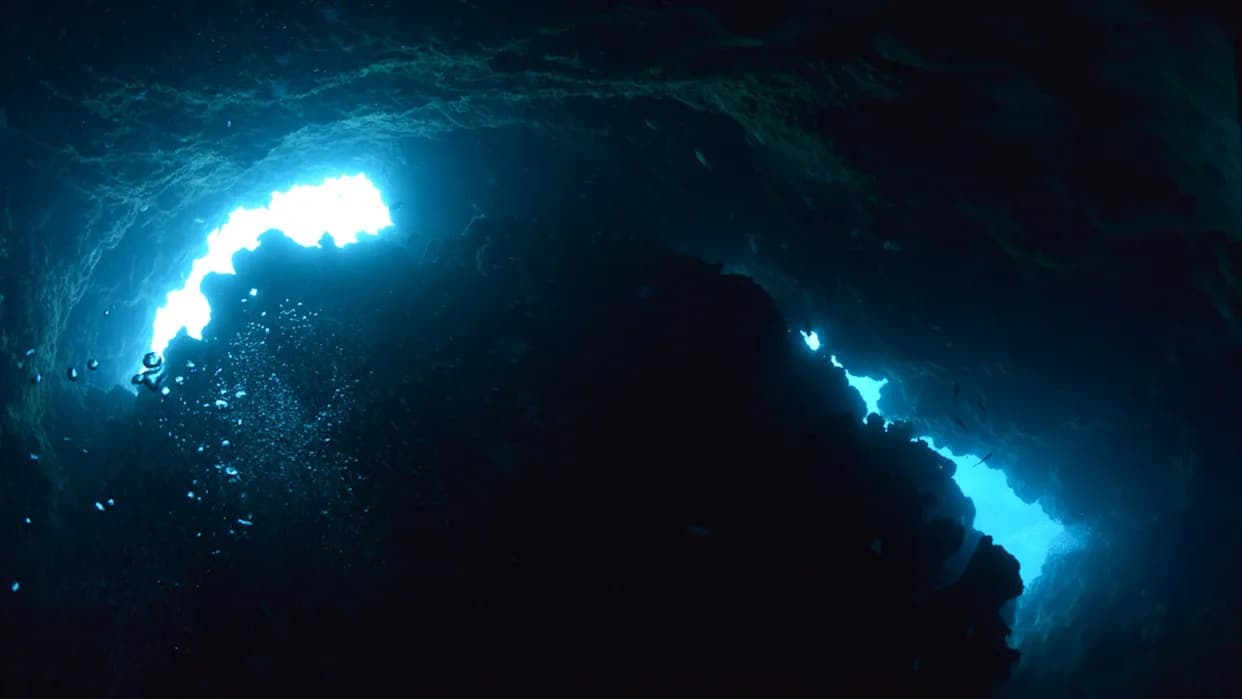

The researchers developed a computer model to track how plastic debris degrades, fragments and interacts with sinking organic aggregates known as marine snow — microscopic, sticky clumps of organic matter that fall from surface waters into the deep ocean. Earlier work assumed plastics would only attach to very small organic particles after shrinking to certain sizes; that assumption left a large gap between estimated plastic inputs and observed surface plastics.

By including processes such as marine-snow settling, fragmentation and the influence of ocean currents, the model reconciles much of that gap: broken-down plastics can adhere to marine snow and be carried downward by the ocean’s biological pump — a “natural conveyor belt” for carbon and nutrients.

Why this matters: Plastic pollution is not only a visible litter problem. Microplastics formed from fragmented larger items are now found in soils, in food webs, in drinking water and even in human tissues. The new findings raise concerns that plastics accumulating in deep-sea sediments could interfere with the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon — a key process that helps regulate atmospheric CO2 and maintain marine ecosystem balance.

The authors warn that the deep-sea accumulation of plastics could potentially alter carbon storage or the functioning of benthic ecosystems, although the magnitude and long-term implications require further study.

Actionable takeaways

- Prevention is critical: stop plastics entering marine systems by reducing single-use products, improving waste management and designing materials for reuse and recycling.

- Mitigation still matters: removing plastics from beaches and surface waters is valuable, but it won’t recover plastics already transported into the deep ocean.

- Research priorities: more observations and experiments are needed to quantify how plastics affect carbon fluxes and deep-sea ecosystems over time.

Conclusion: The study reframes plastic pollution as a transformed and transported problem — not only a surface nuisance but a contaminant moved by natural ocean processes with potential consequences for carbon cycling and marine life. Long-term, systemic solutions across production, use and disposal are essential to limit future harm.

Help us improve.