The long-term ACTIVE trial follow-up found that older adults who completed up to 23 hours of adaptive, speed-based cognitive training (with booster sessions over three years) had a 25% lower risk of dementia across 20 years. Memory and reasoning exercises did not provide the same protection. Experts propose mechanisms such as neuroplasticity, implicit learning and increased cognitive reserve, and emphasize that boosters and adaptive difficulty likely mattered. Clinicians recommend the program for people aged 65+ as part of a broader dementia-risk reduction strategy.

Long-Term Study: Adaptive Speed-Based Brain Training Linked to 25% Lower Dementia Risk Over 20 Years

A major long-term follow-up of the ACTIVE randomized trial found that a specific, adaptive visual processing program — commonly delivered as the "double decision" exercise — was associated with a substantially lower risk of dementia over two decades.

Study Design and Main Finding

The ACTIVE trial enrolled nearly 3,000 adults aged 65 and older across six U.S. regions and followed them for 20 years using linked Medicare records to identify dementia diagnoses. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three cognitive-training programs (speed training, memory training, or reasoning training) or to a no-training control group. Initial training consisted of up to 10 sessions over five weeks; about half of participants in each training arm were offered booster sessions totaling up to 23 hours over three years.

Key result: Participants who completed speed training and received the booster sessions had a 25% lower risk of a dementia diagnosis (including Alzheimer’s, vascular, and frontotemporal forms grouped together) over 20 years compared with the control group. Speed training without boosters did not show the same benefit. Memory and reasoning training provided no detectable long-term reduction in dementia risk.

What Is Speed Training?

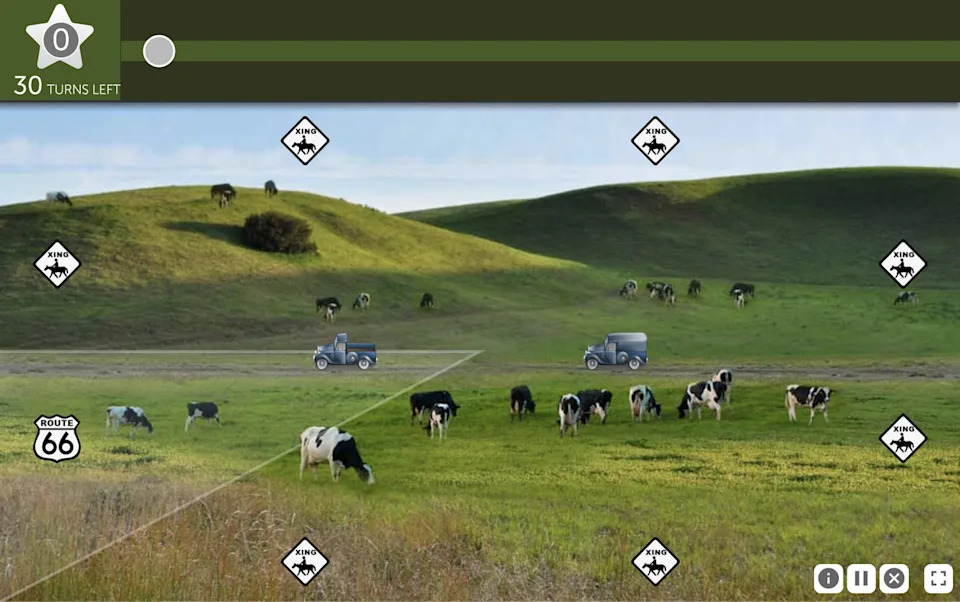

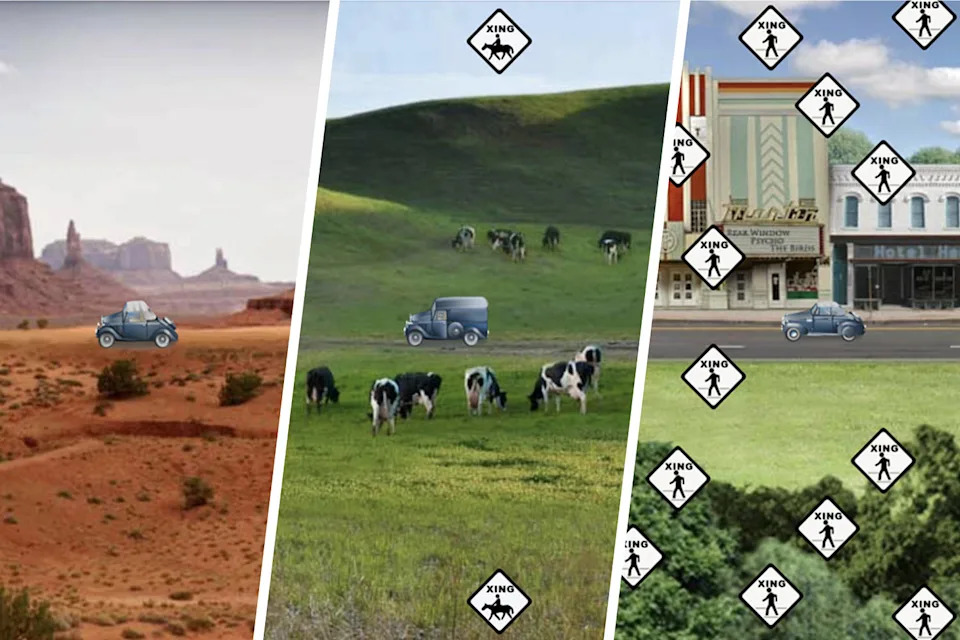

Speed training emphasizes rapid visual processing and decision-making. In the program used for ACTIVE, participants identified objects or scenes on a screen and made quick accuracy-based judgments. The exercise was adaptive: difficulty increased as performance improved, pushing participants to faster, more challenging tasks. The training used in ACTIVE was originally developed by Karlene Ball and Daniel Roenker and later updated; a version called Double Decision is available through BrainHQ.

Why Might It Work?

Experts suggest several, nonexclusive mechanisms:

- Neuroplasticity: Repeated practice on rapid visual tasks may rewire or strengthen neural circuits, producing durable changes.

- Implicit vs. explicit learning: Speed training may rely more on implicit learning (automatic skills) rather than explicit memorization, and implicit changes can be long-lasting.

- Cognitive reserve: Broad engagement of neuronal networks during adaptive, challenging tasks may build resilience that helps the brain withstand pathology.

- Adaptation and intensity: The adaptive nature and booster sessions may be essential; modest initial training alone did not produce the same effect.

“It builds on the concept that relatively small amounts of effort can really pay dividends for decades to come,” said Dr. Richard Isaacson, who was not involved in the study.

Clinical Context and Recommendations

Researchers and clinicians caution that dementia is complex and unlikely to be prevented by a single intervention. Nonetheless, based on the ACTIVE results, some experts now recommend adaptive speed-based training for adults aged 65 and older — the population actually studied. It remains unclear whether starting similar training at younger ages (for example in one’s 40s or 50s) would provide the same long-term protection; further research is needed.

The trial’s authors and commenting clinicians also emphasize addressing proven, modifiable risk factors. Practical measures commonly advised include:

- Hearing screening and correction

- Managing metabolic risk (blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar)

- Correcting vision impairment

- Regular physical activity, which supports cerebral blood flow (combining exercise with cognitive tasks may add benefit)

- Staying socially and mentally engaged

In addition, a large observational study published in Nature reported that shingles vaccination was associated with about a 20% lower dementia risk over seven years, suggesting vaccines and other public health measures may also play a role in reducing dementia incidence.

Limitations

Key limitations include that dementia diagnoses were captured through Medicare records rather than in-person clinical adjudication for all participants, and different dementia types were grouped together for analysis. The study was randomized for the training arms, but long-term observational follow-up can still be affected by differences in health care use, follow-up, and other factors. Finally, the protective effect was specific to the adaptive speed training with booster sessions used in ACTIVE and may not generalize to all brain-training programs.

Bottom Line

Adaptive, speed-based cognitive training with booster sessions in later life was associated with a meaningful reduction in dementia diagnoses over 20 years in a large randomized trial. While not a standalone solution, this form of training may be a useful addition to a broader strategy for brain health that includes managing vascular and sensory risks, exercise, social engagement, and preventive care.

Help us improve.