The Carter Center reported a historic low of 10 human Guinea worm cases in 2025, concentrated in Chad (4), Ethiopia (4) and South Sudan (2). This represents a 33% decline from 2024, though animal infections—particularly in Cameroon and Chad—remain a major hurdle. The program prioritizes community education, water filters and new diagnostic tests for early detection in animals to accelerate eradication.

Historic Low: Just 10 Human Guinea Worm Cases Reported in 2025, Carter Center Says

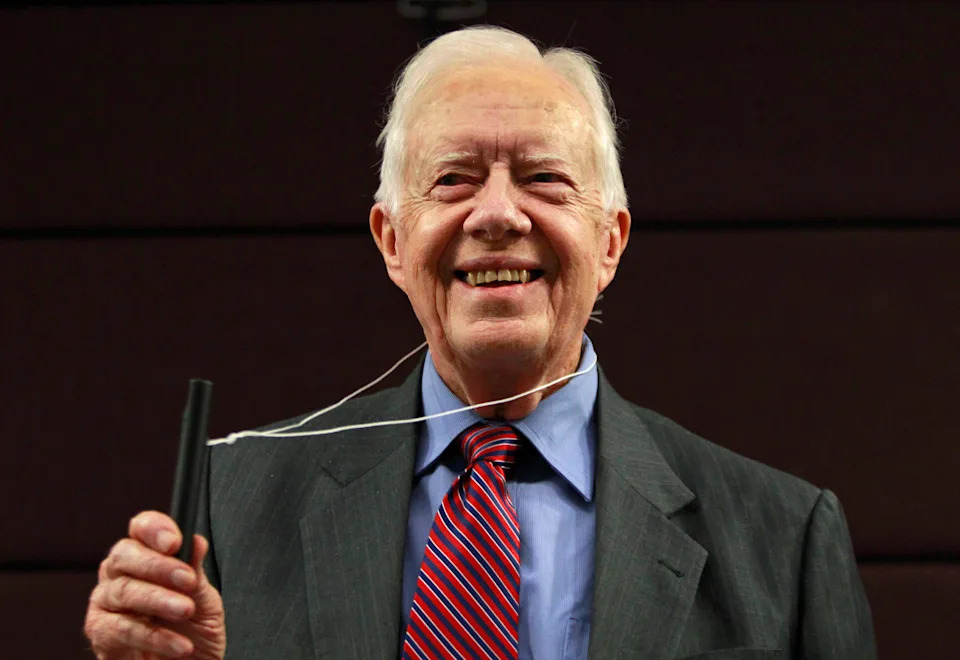

ATLANTA (AP) — Global human cases of Guinea worm disease fell to a historic low of just 10 in 2025, The Carter Center announced Friday. The infections were concentrated in three countries as eradication efforts launched in the 1980s by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter continue to push the disease toward extinction.

Progress and Current Numbers

In 2025, reported human cases included four in Chad, four in Ethiopia and two in South Sudan, a 33% decline from 15 cases in 2024. Several countries — including Angola, Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Mali — reported zero human cases for the second consecutive year.

The Carter Center also reported animal infections remain in the hundreds, which complicates eradication efforts: Cameroon reported 445 animal infections, Chad 147 (a 47% drop from its peak), Angola 70, Mali 17, South Sudan three and Ethiopia one.

“We think about President Carter's legacy,” said Adam Weiss, director of the Carter Center’s Guinea worm eradication program. “These might not be the number one problems in the world, but they are the number one problems for the people who suffer from them. We remain committed to his mission of alleviating pain and suffering.”

How Transmission Happens

Guinea worm is contracted by drinking water contaminated with larvae. Inside a person the parasite can grow to roughly a meter in length and eventually emerges painfully through a blister on the skin. Transmission occurs when infected people or animals enter water sources and release larvae, or when people consume fish or amphibious creatures that have ingested larvae.

Response and Next Steps

The Carter Center, working with national health ministries, the World Health Organization and local partners, focuses on public education, training community volunteers and distributing water filters in affected communities. There is no drug that cures Guinea worm; treatment is limited mainly to pain relief and careful removal of the worm where possible.

Looking ahead, program leaders say their top priority is developing reliable diagnostic tests, especially for animals, so infections can be detected long before symptoms appear. Early detection would allow behavioral changes that reduce the risk of contaminating shared water sources and accelerate eradication efforts.

Legacy and Logistical Challenges

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter traveled extensively in affected countries to help build coordinated eradication campaigns alongside health ministries and international organizations. Weiss noted that policy and funding changes abroad — including the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization under former President Donald Trump and related reductions in funding for some international aid programs — required logistical adjustments, but have not stopped field-level eradication work.

If Guinea worm is fully eliminated in humans, it would join smallpox as one of only two diseases ever eradicated in humans.

Help us improve.