The author argues that President Trump’s public attacks on officials have unexpectedly prompted grand jurors to act more independently, restoring a check the Framers intended. Structural features like Rule 6 historically favored prosecutors, but recent refusals to indict in high-profile matters suggest jurors are exercising skepticism. The investigation into Fed Chair Jerome Powell faces added obstacles if jurors perceive political motives. Ordinary citizens on grand juries are now serving as an important guard against prosecutorial overreach.

How Trump’s Attacks May Have Restored the Grand Jury’s Original Role

In 1985, former New York Chief Judge Sol Wachtler quipped that a prosecutor could "indict a ham sandwich." As a former U.S. district judge, I saw for decades how that witticism reflected a practical reality: federal grand juries too often operated as an almost automatic gateway to indictment, returning charges quickly and uniformly.

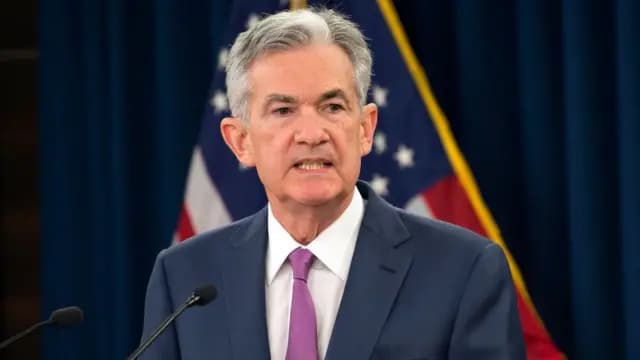

We may be witnessing a notable reversal. Reports that Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has been served with grand jury subpoenas in a probe of testimony about Fed headquarters renovations are being seen by many as another episode in which the Trump administration appears to be using the Justice Department as an instrument of political pressure.

Yet, ironically, President Trump’s overt targeting of officials may have nudged the federal grand jury back toward the independent safeguard the Framers intended. By publicly naming figures such as James Comey, Letitia James and Jerome Powell as "enemies," the president has stripped away any pretense of neutrality that might surround investigations of those individuals.

Why Grand Juries Historically Favored Prosecutors

Part of the grand jury’s historical deference is structural. Under Rule 6 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, prosecutors control the proceedings: there is no judge present and defense counsel ordinarily does not participate. An accused person may testify, but most decline because they would face the prosecutor alone and risk self-incrimination.

Within that framework a prosecutor can present a curated view of the evidence, making it likely that at least 12 of the typical 23 jurors will vote to indict. Grand jury votes have often been unanimous, and once someone is designated a "target," an indictment can feel more like arithmetic than judgment.

Signs of a Shift

Recent developments suggest jurors are exercising independent judgment. Federal grand juries in Alexandria and Norfolk reportedly declined to re-indict New York Attorney General Letitia James—twice in a week—after an earlier prosecution was dismissed. Prosecutors likewise failed to secure certain charges in matters involving former FBI Director James Comey. And in a case that drew public attention, a grand jury declined to return a felony indictment against Sean Dunn—the so-called "D.C. sandwich guy"—after he allegedly assaulted a federal officer by throwing a Subway footlong at a Border Patrol agent.

In these instances, ordinary citizens sitting without a judge or defense counsel weighed the evidence the government presented and said no. My assessment is that many jurors detected political overtones and chose not to authorize charges they perceived as thin or politicized.

The Powell Investigation And A New Hurdle For Prosecutors

The DOJ says it is investigating alleged perjury by Fed Chair Jerome Powell about construction costs for Federal Reserve office buildings—an inquiry Powell has called a "pretext" tied to disagreements over interest-rate policy. As that matter moves toward a grand jury, the administration’s open hostility toward Powell has likely signaled to prospective jurors that politics may be in play. Unless prosecutors can present evidence that clearly transcends political theater, I have serious doubts a grand jury will return an indictment.

Restoring The Framers’ Check

By weaponizing the Justice Department so visibly, the administration may have inadvertently ended the era of the passive grand jury. Jurors now enter deliberations with greater skepticism, doing precisely what the Framers intended: serving as a democratic check on prosecutorial overreach and a shield for individuals against politically motivated prosecutions.

Credit where it is due. Whether intended or not, these developments have reminded Americans that citizens sitting on grand juries are essential arbiters of fairness. When jurors choose principle over pressure, they become an essential safeguard of our constitutional order.

John E. Jones III is president of Dickinson College and a former chief judge of the U.S. Middle District of Pennsylvania.

Copyright 2026 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.

Help us improve.