Researchers at the University of Calgary and Canada’s National Research Council report that living tissues emit an ultraweak visible light (UPE) that falls sharply after death. Using EMCCD and CCD cameras, they imaged four mice alive and after euthanasia and observed a significant drop in photon counts post-mortem. Parallel experiments on Arabidopsis thaliana and Heptapleurum arboricola leaves showed injured areas glowed brighter for at least 16 hours, implicating reactive oxygen species. The signals are extremely faint, recorded under controlled conditions, and require further validation before practical use.

Living Tissues Emit a Faint Visible Glow That Fades at Death, Study Finds

Researchers from the University of Calgary and the National Research Council of Canada report experimental evidence that living tissues produce an ultraweak visible light emission that declines sharply after death.

The team, led by physicist Vahid Salari, combined whole-animal imaging and plant experiments to detect single-photon emissions from living mice and leaves of two plant species, then observed a clear drop in those emissions once life ceased or after tissue injury dynamics changed.

Background

At first glance, the idea that organisms emit visible light can sound fringe, evoking discredited claims about auras. But the phenomenon — often called biophoton emission or ultraweak photon emission (UPE) — has a foundation in chemistry and biology. Chemiluminescence and other light-producing reactions are well documented, and spontaneous optical emissions across roughly 200–1,000 nanometers have previously been reported from isolated tissues and cell cultures.

How The Study Was Done

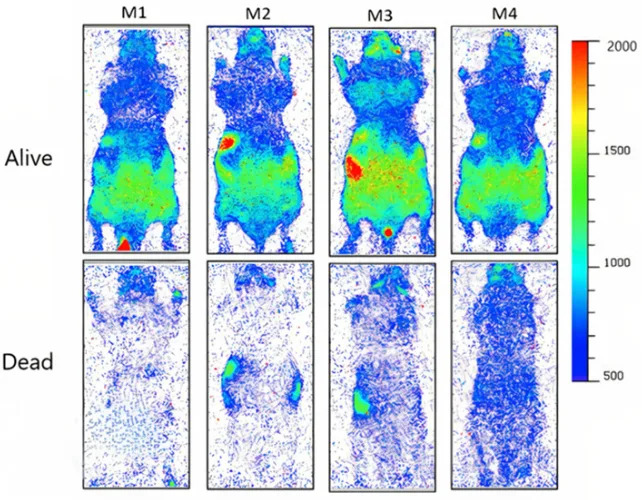

To test whether UPE can be measured across whole bodies, the researchers used electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) and charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras optimized for extremely low-light imaging. Four immobilized mice were placed individually in a dark enclosure and imaged for one hour while alive, then euthanized and imaged for another hour. The animals were kept at body temperature after death so that changes in heat output would not confound the optical measurements.

Key Findings

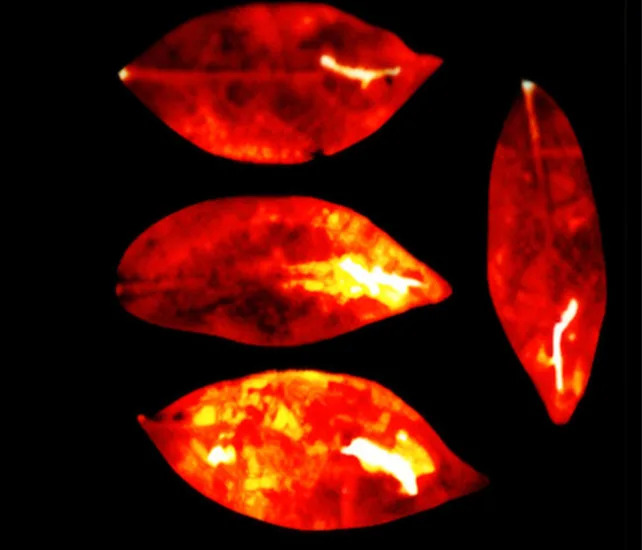

The team reported they could register individual visible-band photons from mouse tissues and that the photon count dropped significantly following euthanasia. Complementary plant experiments on Arabidopsis thaliana and Heptapleurum arboricola (dwarf umbrella tree) leaves produced similar patterns: mechanically injured or chemically stressed leaf regions emitted brighter light, and injured areas remained brighter over 16 hours of imaging.

“Our results show that the injury parts in all leaves were significantly brighter than the uninjured parts of the leaves during all 16 hours of imaging,” the authors report, linking the glow to stress-induced chemistry.

Proposed Mechanism and Implications

A leading candidate for these emissions is reactions involving reactive oxygen species (ROS). When oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide react with lipids and proteins, molecular transformations can transiently excite electrons; as those electrons relax, they can emit single photons in the visible range. If UPE correlates reliably with tissue stress, non-invasive optical monitoring could become a useful tool for medical diagnostics, agricultural monitoring, or microbiology.

Limitations and Caution

Important caveats accompany the results: the signals are extremely weak and were recorded under tightly controlled, dark conditions with specialized cameras. The mouse sample was small (four animals), and the findings do not yet demonstrate that similar signals can be detected under everyday conditions in humans. Additional studies with larger sample sizes, rigorous controls, and independent replication are needed before clinical or agricultural applications can be realized.

The study was published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. An earlier version of this article appeared in May 2025.

Help us improve.