Surveys show that most Americans — even in conservative regions — hold positive views of wolves. A Jan. 6, 2026 study of over 2,200 people across nine wolf-populated states found that simply reminding people of their political party made opinions about wolves significantly more polarized. This polarization was driven largely by misperceptions of fellow partisans' views; when participants saw the true distribution of party opinions, their attitudes moderated. Emphasizing shared and cross-cutting identities can further reduce conflict and improve dialogue about wildlife management.

Most Americans Like Wolves — Political Reminders Polarize Opinions, Study Finds

Management of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) is often portrayed as one of the most bitter conservation debates in the United States. Dramatic images — jubilant reintroductions to places like Yellowstone and Colorado set against angry ranchers and pro-wolf protests countered by hunters — suggest a deep, irreconcilable split.

But long-running survey evidence tells a different story: most people in the U.S. and around the world hold broadly positive views of wolves. That pattern holds even in politically conservative states often assumed to oppose wolf conservation. For example, a recent Montana study found that 74% of residents in 2023 reported being tolerant or very tolerant of wolves.

The Question

We asked whether the vivid portrayals of partisan conflict — and the assumptions about division they reinforce — might actually help produce the polarization they describe. In a study published Jan. 6, 2026, we investigated whether simply reminding people of their political party affiliation would change how they perceive wolves.

Who We Are And How We Studied This

We are social scientists who study the human dimensions of environmental issues, from wildfire to wildlife. Using tools from psychology and related social sciences, we examine how people relate to nature and to one another. Often, these social dynamics matter more for conservation outcomes than the biology itself: many conservation challenges are fundamentally people problems.

Key Psychological Mechanisms

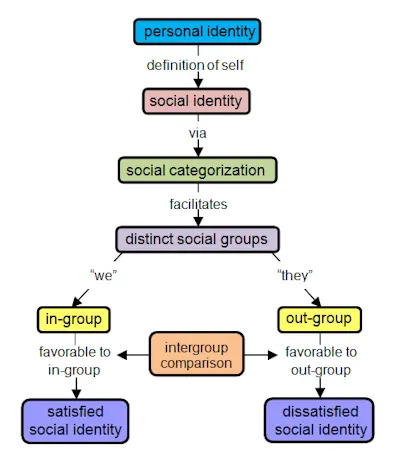

Social identity — the tendency to sort into groups and treat group boundaries as meaningful — strongly shapes how people perceive issues. Once people see themselves as part of a group, they tend to favor the "in-group" and be wary of "out-groups." Extreme identification can lead to identity fusion, where personal identity becomes tightly bound to group identity, sometimes prompting actions people would otherwise avoid.

What the Study Found

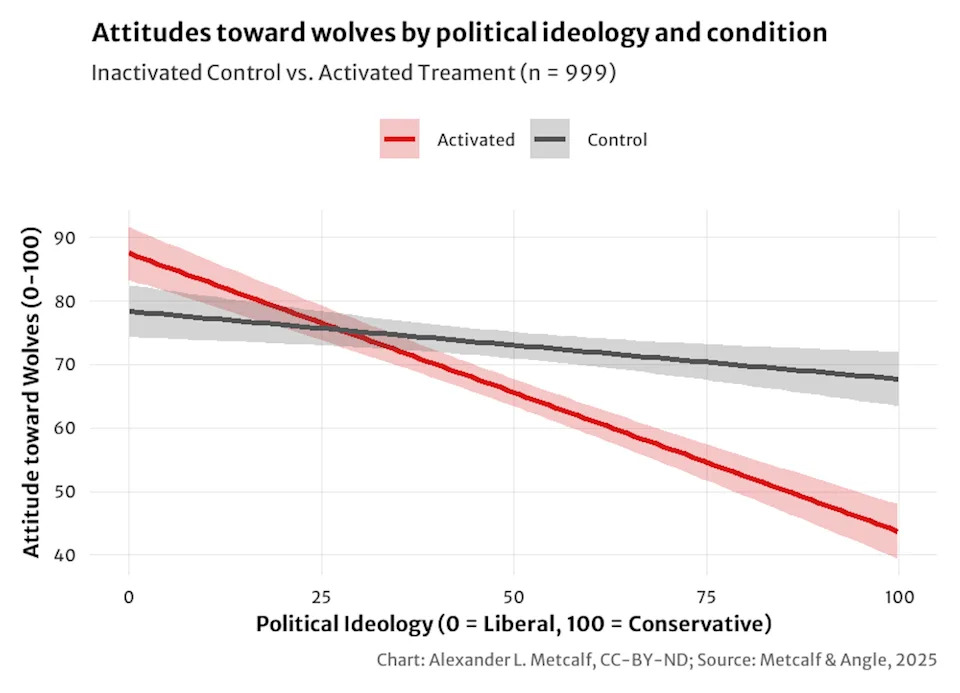

Across two experiments with more than 2,200 participants from nine states that contain wolf populations, we found a clear pattern. When participants' political identities were activated — for example, by reminding them of their party affiliation — attitudes about wolves became more polarized: Democrats reported stronger positive feelings about wolves, while Republicans reported greater aversion.

By contrast, when political identity was not made salient, people generally expressed favorable views of wolves regardless of party. A follow-up experiment showed that this polarization was driven largely by misperceptions about the in-group: participants assumed that fellow party members held more extreme views about wolves than they actually did, and those mistaken beliefs influenced their own attitudes.

Why This Matters

In short, caricatures of partisan division helped produce the division. A situation in which many people actually agree became polarized not because of deep-rooted differences but because of how people imagined others felt. That is both ironic and potentially reversible.

Paths Toward Less Polarization

The same psychological mechanisms that promote division can also reduce it. When participants were shown the actual distribution of views within their party — specifically that most fellow partisans held positive attitudes toward wolves — their own attitudes moderated. Other promising strategies include:

- Highlighting Cross-Cutting Identities: Emphasize identities that span divides (e.g., rancher and conservationist, or hunter and wildlife advocate).

- Emphasizing Shared Memberships: National, community, or local identities can reduce an "us vs. them" mindset and open space for productive conversation.

- Correcting Misperceptions: Publicizing accurate information about peer views can reduce exaggerated expectations of partisan extremity.

Conclusion

The debate over wolves may appear to be an intractable clash of values, but our research suggests it need not be. When people move beyond caricatures of conflict and recognize the common ground that already exists, the tone of discussion can shift — potentially helping communities find practical ways to coexist with wolves and with each other.

Authors and Disclosure: This research was conducted by Alexander L. Metcalf and Justin Angle, University of Montana. The authors report no relevant financial interests or affiliations that would bias the research. This article is republished from The Conversation.

Help us improve.