A Bar-Ilan University study finds that jellyfish and related Cnidaria sleep about one-third of each day despite lacking a central brain. Experiments showed that sleep deprivation, UV exposure, and mutagens increased neuronal DNA damage, while melatonin increased sleep and reduced damage. The authors suggest sleep evolved early to enable cellular repair and maintain genome stability.

Jellyfish Sleep Like Humans — Study Suggests Sleep Evolved Nearly a Billion Years Ago

A new study from Bar-Ilan University in Israel shows that jellyfish—boneless, gelatinous animals without a centralized brain—spend about one-third of each day asleep. The findings, published in Nature Communications, suggest sleep is an ancient trait that may have evolved to protect neurons from damage.

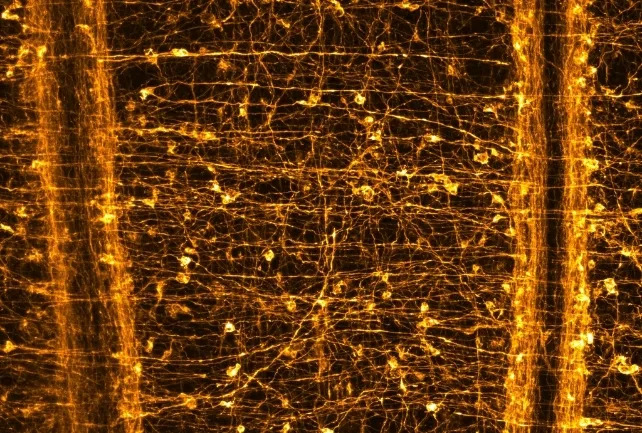

Researchers studied upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda) and the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis), both members of the Cnidaria phylum. Although Cnidaria lack a centralized brain and instead possess a distributed nerve net, these animals display clear sleep-like behaviors: periods of immobility, reduced responsiveness, and daily regularity in sleep timing.

Sleep and Cellular Damage

Under laboratory and natural conditions, the team observed that sleep deprivation increased neuronal DNA damage in both species. Environmental stressors—such as ultraviolet radiation and chemical mutagens—that raised DNA damage also increased the animals' need for sleep. When researchers treated the animals with melatonin, the animals slept longer and showed reduced DNA damage.

"Sleep deprivation, ultraviolet radiation, and mutagens increased neuronal DNA damage and sleep pressure," the authors report. "Spontaneous and induced sleep facilitated genome stability."

The investigators conclude that wakefulness allows DNA damage and cellular stress to accumulate, while sleep provides a consolidated window for efficient repair and maintenance at the level of individual neurons. This cellular-protection hypothesis helps explain why even simple nervous systems appear to require sleep.

Why This Matters

Human ancestors diverged from the lineage leading to cnidarians hundreds of millions to roughly a billion years ago, so the presence of sleep-like states in Cnidaria implies that the basic need for sleep predates complex brains. The study strengthens the idea that one of sleep's most ancient roles was to preserve genome stability and support cellular repair in nervous tissue.

Study Details: Authors include Raphaël Aguillon, Harduf, and colleagues at Bar-Ilan University. The research was published in Nature Communications.

Help us improve.