The article argues that extraordinary beliefs — from flat‑Earth claims to spirit encounters and conspiracy theories — arise largely because people interpret their experiences as evidence. It identifies three mechanisms: experience filters which false ideas feel plausible, unusual experiences spark supernatural explanations, and immersive rituals produce convincing subjective evidence. Understanding these pathways can improve strategies to counter harmful misinformation and foster empathy toward believers.

How Experience Shapes Extraordinary Beliefs: From Flat Earth to Spirits and Conspiracies

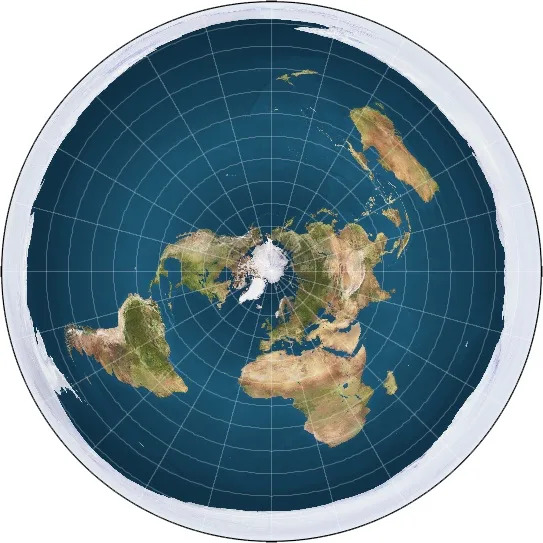

On Feb. 22, 2020, “Mad” Mike Hughes launched a homemade rocket from the Mojave Desert hoping to see the shape of the Earth with his own eyes. The flight ended tragically: Hughes crashed shortly after takeoff and died. At first glance his nickname — and his mission — may seem irrational: why risk your life to test something settled by science centuries ago?

As an evolutionary anthropologist, I find that question worth asking more broadly. Across cultures and history, people adopt firm convictions that appear to lack clear empirical support — what researchers call extraordinary beliefs. Examples range from flat‑Earth ideas and spirit encounters to vaccine microchip conspiracy theories.

In a recent review in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, I argue that these beliefs arise for the same basic reason most beliefs do: people interpret their experience as evidence. While cognitive biases and social dynamics are important, direct experience plays three complementary roles in creating and sustaining extraordinary beliefs.

Three Ways Experience Shapes Belief

1. Experience Filters Which Ideas Spread

Not all incorrect ideas are equally persuasive. The flat‑Earth claim has far more cultural traction than an equally wrong hypothesis such as “the Earth is a cone.” One simple reason: everyday perception makes the planet look flat from the surface. Visual experience favors some erroneous models over others, providing an intuitive filter that guides which theories are plausible to nonexpert observers.

2. Experience Sparks Explanatory Stories

Unusual or distressing experiences demand interpretation. Sleep paralysis — a state between sleep and waking in which people feel immobilized and often sense a threatening presence on their chest — illustrates this. Neuroscientists explain sleep paralysis as a temporary mismatch between waking awareness and motor control circuits. For someone without that scientific framework, however, the episode can plausibly be read as an encounter with a spirit or malicious agent.

3. Immersive Practices Produce Convincing Evidence

Many traditions create vivid experiences that function as subjective evidence for particular beliefs. In Lesotho, where I conduct ethnographic fieldwork, a farmer who suffers repeated miscarriages might consult a traditional healer and drink a hallucinogenic brew to commune with ancestors. The ensuing visions and voices provide powerful, first‑person confirmation that ancestors are involved — and ritual, social reinforcement further cements that belief.

Prayer, ritual dance, fasting, and the ceremonial use of psychoactive substances all create perceptual and social contexts that make associated beliefs feel true to participants.

Why This Perspective Matters

Extraordinary beliefs are not inherently good or bad. Religious convictions can supply meaning, comfort, and community for billions of people. But some beliefs — especially scientific and political misinformation — can be harmful and widespread.

Recognizing how experience interacts with cognitive biases and social dynamics helps in two ways. First, it suggests more empathetic and effective interventions: rather than dismissing believers as irrational, communicators can address the perceptual and social roots of conviction. Second, it points to concrete strategies to counter dangerous falsehoods, such as offering alternative, credible experiences, improving science education about perception and cognition, and building trust within communities.

People who endorse surprising ideas are often sincere interpreters of their own experiences, not merely obstinate or deceitful. Understanding that can open more productive and compassionate conversations.

Help us improve.