Summary: The Supreme Court is now accepting and deciding far more cases tied to culture‑war issues — religion, guns, LGBTQ rights and abortion — than it did during the Obama years. In five terms after Justice Barrett’s confirmation the Court heard 18 such cases versus about 12 across Obama’s eight terms (an average of 3.6 vs. 1.5 cases per term). Key drivers include the justices’ power to choose cases, a stable 6–3 conservative majority, strategic litigation by states and advocates, and the need to clarify confusing new doctrinal tests such as Bruen. If the conservative majority endures, the docket may normalize over time, but for now the Court remains deeply engaged in cultural disputes.

Supreme Court Turns Into A Culture‑War Battleground — More Cases On Religion, Guns, LGBTQ Rights And Abortion

The Supreme Court today devotes a far larger share of its docket to politically charged cultural issues — religion, guns, LGBTQ rights and abortion — than it did in recent years. Several forces explain the shift: the justices' ideological priorities, conservative litigants and state officials seizing a perceived friendly bench, and the Court's need to clarify novel or sweeping legal rules it recently announced.

What Changed?

For much of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the Court functioned largely as a technocratic body that decided many routine legal disputes and only occasionally issued landmark, highly politicized rulings. Landmark names such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and Roe v. Wade (1973) are familiar exceptions. Today, however, culturally salient disputes make up a much bigger slice of the Court's docket.

The Evidence

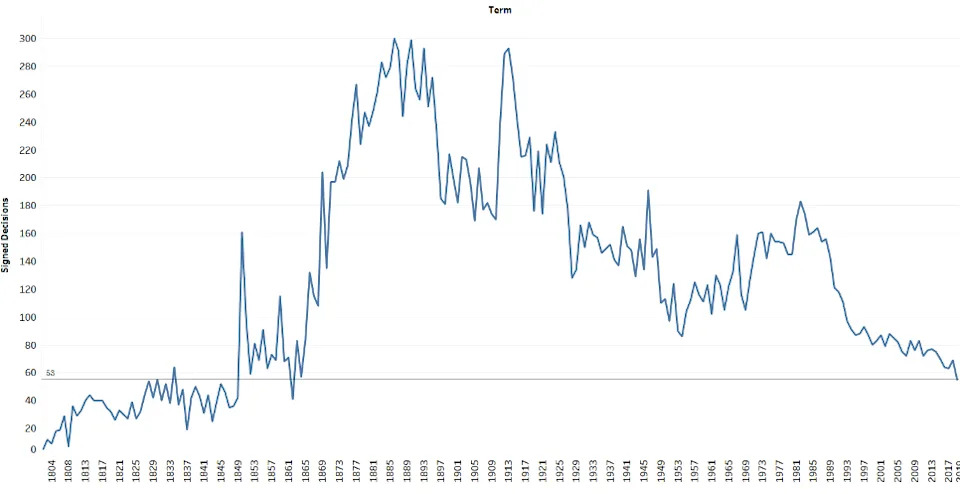

Using consistent criteria, the analysis compared two windows: the eight Supreme Court terms that began while Barack Obama was president (October 2009 through October 2016) and the five full terms after Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the Court (2021–22 through 2025–26). I counted only cases that received full briefing and an oral argument, and excluded emergency or expedited rulings commonly called the shadow docket.

Results: the Court decided roughly a dozen "culture‑war" cases in the eight Obama-era terms and 18 such cases in the five terms after Barrett's confirmation — about 1.5 culture‑war cases per term under Obama versus about 3.6 per term more recently. This shift occurs even as the Court's total number of fully briefed, argued cases has fallen (the 2024–25 term included just 62 such cases).

Which Issues Counted?

I focused on four categories: abortion, guns, LGBTQ rights and religion. Each category required that the Court's holding determine substantive legal rights or constitutional doctrine in that area. Routine criminal prosecutions involving guns, jurisdictional or procedural disputes about abortion when no substantive right was resolved, and cases where LGBTQ status or religion were incidental to the main legal question were excluded.

Why The Shift?

Several factors help explain the Court's new orientation:

1. Case selection power: The Supreme Court largely chooses which cases to hear. A majority that shares ideological priorities can select disputes likely to advance those priorities.

2. Stability of a Conservative Majority: A 6–3 conservative bloc reduces the political risk of taking on contentious issues such as abortion or affirmative action. Where earlier alignments left outcomes uncertain, the current majority often votes as a bloc or narrows dissents.

3. Litigant and Legislative Behavior: Conservative states and private litigants have brought suits and enacted laws they likely would have avoided when lower courts were more hostile. That produces more cases that can reach the justices.

4. Doctrinal Confusion: Recent landmark rulings have produced novel tests that lower courts struggle to apply. For example, the Bruen framework requires evaluating whether modern gun regulations are "relevantly similar" to historical analogues — a standard that many judges find difficult to operationalize, producing repeated appeals to the Supreme Court for clarification.

Examples And Trends

Religion cases have long been a steady part of the docket: eight of the roughly 12 culture‑war cases in the Obama-era window involved religious claims (for instance, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, 2014). By contrast, abortion and Second Amendment cases have risen sharply under the conservative supermajority. The Court issued three major abortion rulings since the conservative bloc gained a supermajority (including Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 2022) and has decided several Second Amendment cases while scheduling more for current terms.

Notable procedural choices in the analysis: the 2020–21 term was omitted because many argued cases that term were selected before Barrett joined; shadow‑docket rulings were excluded to focus on fully briefed, argued decisions. (Including the shadow docket would accentuate the post‑Barrett tilt toward culture‑war topics.) A spreadsheet of cases and coding decisions accompanies the research.

What This Means Going Forward

If the conservative majority remains in place for many years, the culture‑war docket could eventually shrink: the justices may exhaust the list of precedents they wish to overrule and clarify unsettled doctrines that now generate repeated appeals. But for the near term the Court is actively reshaping major cultural and constitutional questions, and it appears intent on leaving a lasting imprint on areas of intense public debate.

Methodological note: Counts include only fully briefed cases that received oral argument and were decided on the merits. High‑profile rulings that resolved purely procedural or jurisdictional issues were excluded, as were some statutory decisions that did not raise constitutional questions.