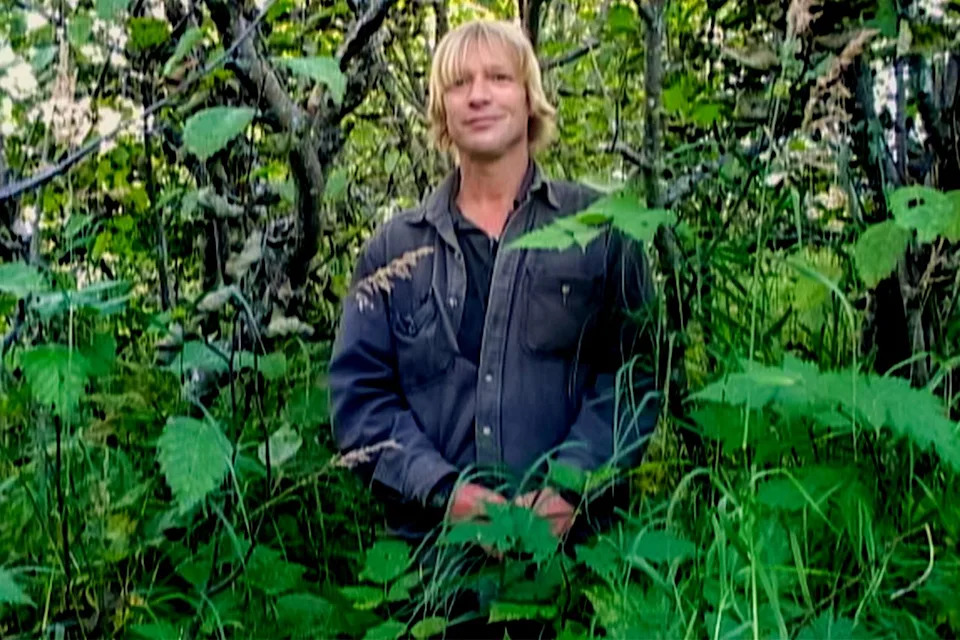

Timothy Treadwell spent 13 summers living among grizzlies in Katmai National Park before he and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, were killed by a male grizzly in October 2003. A six-minute audio clip of the attack was recovered from his camera; longtime friend Jewel Palovak kept the tape for years and recently destroyed it, saying the act felt "very freeing." Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man and later documentaries have kept Treadwell’s controversial legacy and the debate over his methods alive.

Friend Says She Destroyed Audio of Timothy Treadwell’s Fatal Grizzly Attack — 'It Felt Freeing'

Timothy Treadwell spent 13 summers living among grizzly bears in Alaska’s remote Katmai National Park, drawing both praise for his conservation advocacy and criticism for the risks he took. In October 2003, Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, were killed and partially eaten by a male grizzly — an event captured in part by Treadwell’s own camera and later featured in Werner Herzog’s acclaimed film Grizzly Man.

The Recording and Its Destruction

Authorities recovered a video camera at the scene that contained a roughly six-minute audio-only clip of the attack. Jewel Palovak — Treadwell’s longtime friend, former partner and co-founder of the advocacy group Grizzly People — says she never listened to the tape. For years she kept it locked in a safety deposit box. A few years ago she says she finally smashed the tape with a hammer, cut it into pieces and discarded it.

"It felt very good to do that. It felt freeing, very freeing," Palovak told PEOPLE.

The Attack and Aftermath

According to Alaska state trooper reports, Treadwell, 46, and Huguenard, 37, a physician assistant, were attacked at their campsite in October 2003 by a large male grizzly estimated to be about 28 years old and weighing roughly 1,000 pounds. A pilot who returned the next day saw what appeared to be a bear standing over a body. When park rangers arrived in foggy, rain-soaked conditions the animal charged and was killed. Human remains and body parts were later found in the bear’s gut.

State trooper Chris Hill told reporters in 2003 that the recovered audio contained frantic screaming and directions, including calls to "play dead" and to hit the bear with a pan or can. The recording captured the terror of the scene more than the sounds of the bear itself.

Treadwell’s Work and Complex Legacy

A self-taught observer of bears, Treadwell spent over a decade living seasonally among Katmai’s grizzlies, filming and lecturing widely about the animals. He credited the bears with helping him overcome addiction and spoke to thousands of schoolchildren about protecting wildlife from hunters, poachers and habitat loss. Palovak says his goal was to reveal what he called the "secret life of grizzly bears" and to inspire stewardship in younger generations.

Public reaction to Treadwell’s methods has always been divided: some called him an impassioned protector and educator, others criticized his close contact with wild animals as reckless. Palovak rejects the extremes. "He didn’t have a death wish. He wasn’t stupid," she said.

After the Tragedy

Palovak says the organization they built around Treadwell’s work diminished after his death: "The star of the show was gone and our board members and donors have gone on to other things." Nonetheless, Herzog’s Grizzly Man and subsequent documentaries such as Diary of the Grizzly Man have sustained public interest and debate about Treadwell’s life, his methods and the ethics of intimate wildlife filmmaking.

Palovak — who was warned in Herzog’s film not to listen to the tape — says destroying the audio brought closure. She also notes that Treadwell once joked that if he died, someone should make "a kick-ass movie," and suggested that Herzog’s film fulfilled that darkly ironic wish.

What Remains: The six-minute audio she destroyed is gone, but Treadwell’s footage, Herzog’s film and ongoing documentaries continue to shape how people remember his work and weigh the risks of close human contact with wild animals.

Help us improve.