Researchers at Helmholtz Munich found that mutations in GPX4 cause neurons to die by ferroptosis — an iron-driven form of cell death caused by oxidative membrane damage. Mouse models and patient-derived brain organoids showed matching inflammation and progressive neuronal loss. Chemical inhibition of ferroptosis slowed cell death in experimental systems, suggesting ferroptosis may actively drive neurodegeneration and could be relevant to common diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Ultra-Rare GPX4 Mutation Reveals How Neurons Die — Ferroptosis May Drive Neurodegeneration

Laboratory experiments into an ultra-rare inherited mutation have uncovered a clear mechanism by which neurons die — and point to a membrane-centered, iron-driven process that could be relevant to more common neurodegenerative diseases.

What the Study Found

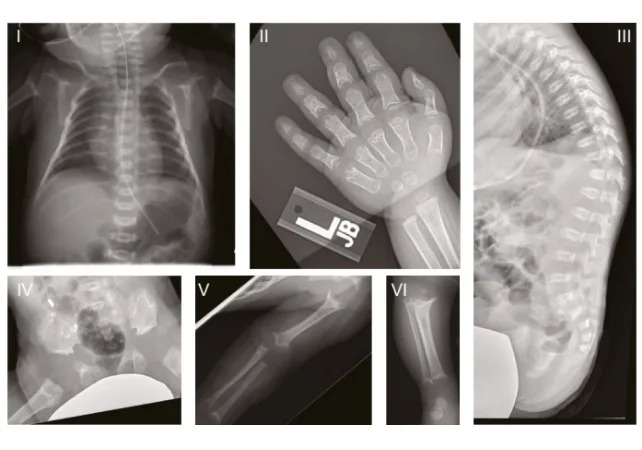

Researchers at Helmholtz Munich linked mutations in the GPX4 gene to progressive inflammation and neuronal loss in mouse models and in human neurons grown from patient skin cells. The human disorder studied, Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SSMD), is an ultra-rare condition first described in 1980 that causes severe brain and skeletal abnormalities and, in many cases, early infant death.

The team studied three U.S. children with SSMD who carried mutations in the same functional region of GPX4. They recreated the genetic defect in mice and generated lab-grown brain organoids from a patient’s skin-derived stem cells; both experimental systems showed similar patterns of neuronal inflammation and cell death.

Ferroptosis: An Iron-Driven Death of Neurons

The investigators show that the neurons die by ferroptosis — a regulated form of cell death initiated by iron accumulation and oxidative damage to membrane lipids (lipid peroxidation). GPX4 is an enzyme that normally protects membranes by detoxifying these lipid peroxides.

With its fin immersed into the cell membrane, it rides along the inner surface and swiftly detoxifies lipid peroxides as it goes.

— Marcus Conrad, Institute of Metabolism and Cell Death, Helmholtz Munich

The specific GPX4 mutations studied prevent the enzyme from anchoring properly to the membrane, leaving neurons vulnerable to oxidative membrane damage and ferroptotic death.

Experimental Rescue and Broader Implications

Neurons derived from SSMD patient stem cells were especially susceptible to ferroptosis. Importantly, treating mice and cultured human neurons with a chemical inhibitor of ferroptosis slowed neuronal loss, indicating that ferroptosis may be a driving force in this form of neurodegeneration rather than a secondary consequence.

Our data indicate that ferroptosis can be a driving force behind neuronal death — not just a side effect.

— Svenja Lorenz, Helmholtz Munich

The authors argue that many dementia studies have focused heavily on misfolded protein aggregates (for example, amyloid-ß plaques), while the primary role of membrane damage and iron-driven lipid peroxidation deserves more attention. Recent evidence already links ferroptosis to Alzheimer’s disease, and the new findings suggest similar membrane-centered mechanisms might contribute to a range of neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Why This Matters

Studying rare, early-onset conditions such as SSMD can provide direct insights into the molecular steps that lead to neuron loss. The work required long-term basic research and multidisciplinary collaboration, and the authors emphasize the importance of sustained funding to decode complex neurodegenerative processes.

Publication: The study was published in the journal Cell.