The Leibniz Institute on Aging used mass spectrometry to compare brain proteins in young and old mice and found age-related changes in ubiquitylation, the chemical tagging that directs proteins for recycling. About one third of the increased tagging was linked to a slowed proteasome in lab-grown human neurons. A four-week calorie-restricted diet in older mice restored youthful tagging patterns for some proteins after they returned to a normal diet. The results, published in Nature Communications, have not yet been tested in living humans but could guide research into disorders like Alzheimer’s.

Aging Scrambles Brain Protein Tags — Short Calorie Restriction Reverses Some Changes

New laboratory research shows that aging alters how proteins in the brain are chemically tagged for recycling, and that a brief dietary intervention can partially restore younger patterns for some proteins.

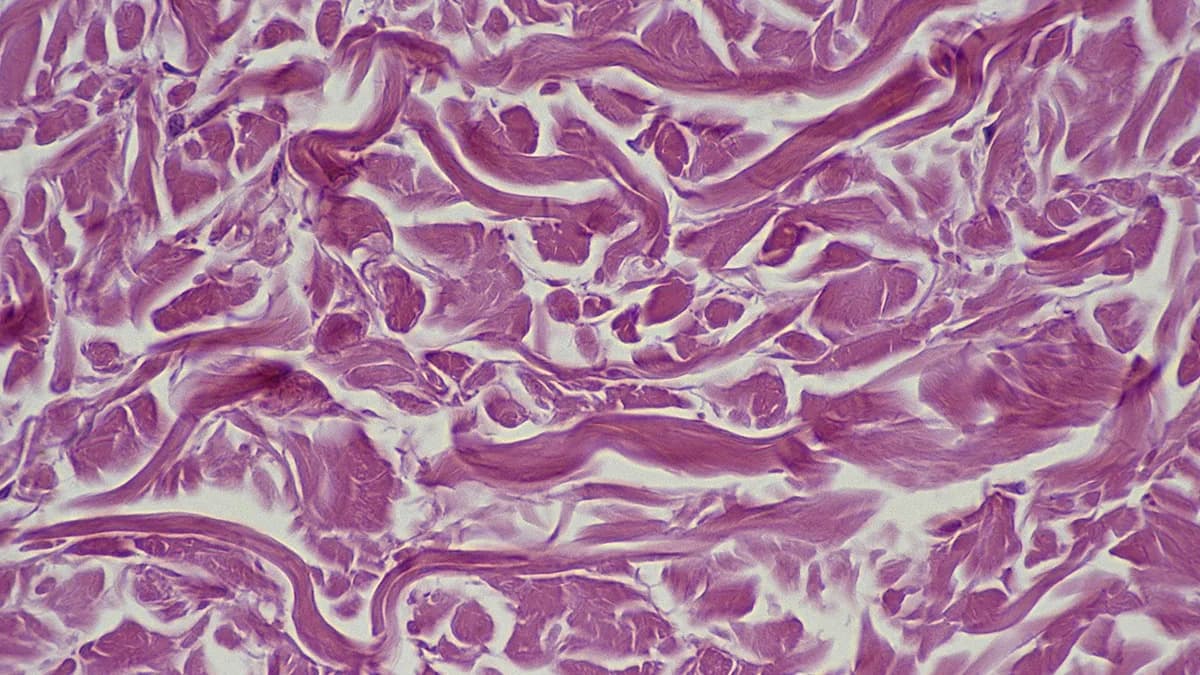

Scientists at the Leibniz Institute on Aging – Fritz Lipmann Institute in Germany used mass spectrometry to compare protein modifications in the brains of young and old mice. Their analysis focused on ubiquitylation, the process that attaches small chemical tags to proteins to mark them for a change in function or degradation.

The team found that many ubiquitylation tags accumulate on particular proteins in older brains instead of being cleared away. To probe why this happens, the researchers studied human neurons grown from stem cells and determined that roughly one third of the excess tagging could be traced to a slowdown of the proteasome, the cell's protein-recycling machinery.

Alessandro Ori, a molecular biologist involved in the study, explains that ubiquitylation acts as a molecular switch that influences whether a protein remains active, changes function, or is degraded. He notes that aging makes this finely tuned system increasingly unbalanced, with some labels accumulating and others being lost irrespective of protein abundance.

To test whether the process can be modified, older mice were placed on a calorie-restricted diet for four weeks and then returned to a normal diet. For a subset of proteins, the pattern of ubiquitylation shifted back toward the profiles seen in younger animals after normal feeding resumed, indicating that diet can influence protein tagging even in later life.

There are important caveats: these experiments were conducted in mice and in laboratory-grown human neurons, and the changes were not uniform across all proteins or quality-control pathways. The researchers did not define the precise molecular mechanisms behind the dietary effect, and the findings have not yet been confirmed in living humans.

Nevertheless, the study advances understanding of how protein homeostasis shifts with age and may inform future strategies to treat conditions where protein balance matters, such as Alzheimer's disease. The full study is published in Nature Communications.

Help us improve.