Northwestern researchers report that NU-9, an experimental drug, substantially reduces toxic amyloid beta oligomers and dampens astrocyte reactivity in mouse models. The team also identified a new oligomer subtype, ACU193+, that appears early in stressed neurons and may drive neuroinflammation. Further preclinical tests in later-stage models are underway before any human trials; researchers caution that amyloid beta’s precise causal role in Alzheimer’s remains unresolved.

NU-9 Slows Early Alzheimer’s Changes in Mice and Reveals New Toxic Oligomer ACU193+

Growing evidence suggests the best chance to treat Alzheimer’s disease is to intervene very early. A team at Northwestern University reports that an experimental compound, NU-9, markedly reduces toxic amyloid beta oligomers in mouse models and appears to blunt early neuroinflammatory changes.

Key Findings

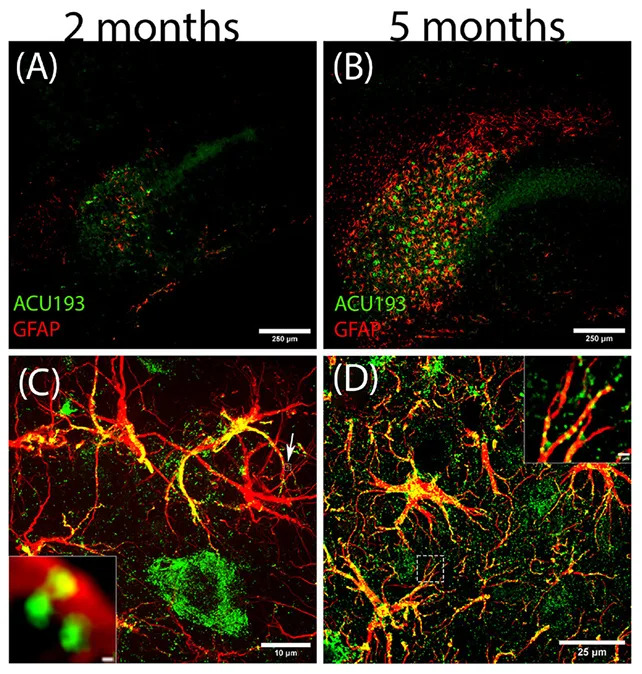

In mice treated with NU-9, researchers measured substantially lower levels of amyloid beta oligomers — small, toxic protein assemblies that can seed the larger plaques historically associated with Alzheimer’s. The reduction in oligomers correlated with calmer, less reactive astrocytes, the brain’s support cells that can contribute to neuroinflammation when overactivated.

“These results are stunning,” said neurobiologist William Klein. “NU-9 had an outstanding effect on reactive astrogliosis, which is the essence of neuroinflammation and linked to the early stage of [Alzheimer’s] disease.”

Discovery of a New Oligomer Subtype

In the study the team identified a previously unrecognized subtype of amyloid beta oligomer, which they named ACU193+. ACU193+ was among the earliest oligomers to appear inside stressed neurons and to associate with astrocytes, suggesting it could trigger the harmful shift in astrocyte behavior that promotes early disease progression.

Context, Caveats, and Next Steps

NU-9 had previously been shown in laboratory studies to prevent amyloid beta oligomer accumulation in human cells grown in vitro; demonstrating similar effects in living animals is an encouraging step. The researchers are now testing NU-9 in animal models that represent later-stage disease to better approximate how Alzheimer’s develops with age in people. Only after additional successful preclinical work could NU-9 enter human clinical trials.

The authors emphasize an important caveat: a direct, exclusive causal role for amyloid beta (oligomers or plaques) in driving Alzheimer’s is not definitively proven, and multiple triggers and interacting factors likely contribute to the disease. This uncertainty may help explain why many clinical trials beginning after symptoms appear have failed.

“Alzheimer’s disease begins decades before its symptoms appear, with early events like toxic amyloid beta oligomers accumulating inside neurons and glial cells becoming reactive long before memory loss is apparent,” said Northwestern neuroscientist Daniel Kranz. “By the time symptoms emerge, the underlying pathology is already advanced. This is likely a major reason many clinical trials have failed. They start far too late.”

If further testing is successful, NU-9 could one day be used as a preventive therapy for people at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s — analogous to how cholesterol-lowering drugs are used to reduce heart disease risk. The full study is published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Help us improve.