Between 1500 and 1700, battlefield injuries and the printing press transformed European attitudes toward amputation and prosthetics. Surgeons moved from a preservation mindset to planning amputations that would accept artificial limbs, while artisans produced intricate spring-driven iron hands. These costly, visible prostheses reshaped social perceptions of disability and helped normalize invasive bodily modification — a conceptual step toward modern implants and prosthetics.

From Saws to ‘Bionic’ Iron Hands: How Renaissance Amputation Reimagined the Human Body

The human body today contains many replaceable parts — from mechanical hearts to myoelectric feet — and that reality depends not only on advanced tools and refined surgical skill, but on a much older idea: that it is legitimate to radically alter a patient’s body by cutting into it and embedding technology.

Many histories point to the American Civil War as the pivotal moment for amputation techniques and prosthetic design. The Civil War did indeed spur a prosthetics industry: surgeons carried out roughly 60,000 amputations and sometimes spent as little as three minutes per limb. But a profound shift in European attitudes toward amputation began centuries earlier, in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Why the Renaissance Mattered

Between about 1500 and 1700, surgeons, artisans and amputees changed how people thought about lost limbs. Two technological developments pushed this change. First, gunpowder weapons produced devastating, contamination-prone wounds that traditional surgical techniques could not reliably treat. Second, the printing press let surgeons publish and widely circulate new methods and case reports, accelerating the refinement of techniques.

From Craft Surgery to Purposeful Amputation

Surgery in the early modern period was learned through apprenticeship and travel. Daily practice mostly involved topical remedies, setting broken bones, lancing boils and stitching wounds. Major operations — amputation or trepanation — were exceptional because of the high risk of death. Wounds from firearms, however, frequently became gangrenous, forcing surgeons to choose between radical removal of damaged tissue and the likely death of the patient.

Surgeons debated not only whether to cut, but how and where to cut. Some argued for conserving as much healthy tissue as possible; others began to plan amputations so that the residual limb would better accept an artificial replacement. For the first time in European surgical writing, amputation strategy was sometimes guided by prosthetic use — a conceptual turn toward seeing the body as material to be fashioned.

Artisans, Amputees and the Rise of the Iron Hand

As surgeons refined techniques, amputees and craftsmen experimented with replacements. Wooden pegs continued to be common for lower-limb loss, but from the late 15th century onward inventive collaborations produced a new prosthetic: the mechanical iron hand.

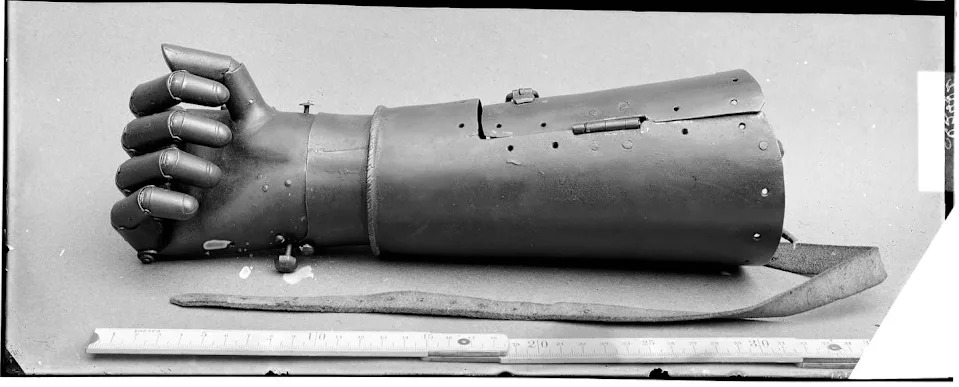

These iron hands were bespoke objects. Internal spring-driven mechanisms let fingers lock into different positions; craftsmen added lifelike details such as engraved nails, skin folds and even flesh-colored paint. Wearers depressed finger shafts to engage locks and released them via a wrist mechanism. Some models moved all fingers together, others allowed individual joint motion; the most sophisticated allowed movement at every joint.

Much of the complexity was as much about social display and mechanical ingenuity as everyday utility. Materials and techniques were borrowed from other crafts — locks, clocks and ornate firearms. Because such bespoke work was costly, iron hands were often owned by wealthier people, making prostheses a visible class marker in a way not seen before.

Beyond the Knight: A Wider Social Story

Scholars have often focused on knights as iron-hand wearers, most famously the 16th-century German knight Götz von Berlichingen. Romantic and dramatic portrayals, such as Goethe’s later play, helped mythologize the prosthesis as a warrior’s arm. But surviving artifacts and documents show many iron hands bore no traces of martial use and may have belonged to civilians, perhaps even women.

In elite culture, mechanical novelties were prized. Amputees used iron hands to resist stigma and to display skill and status; surgeons noted and praised these devices in their treatises. In doing so, iron hands circulated a new material imagination of the body that surgeons began to incorporate into their practice.

Long-Term Significance

This Renaissance reimagining — surgeons shaping stumps to fit prostheses, artisans inventing mechanical limbs, and amputees commissioning and using them — helped make it imaginable that the body could be altered and improved through invasive intervention. That conceptual shift underpins many modern medical practices, from joint replacements to implantable devices.

Note: Documentary evidence yields limited insight into most survivors’ lived experiences; survival rates after major limb amputation may have been as low as 25%. Yet for those who lived, improvisation and collaboration with craftsmen often determined daily mobility and social standing.

This article was written by Heidi Hausse, Auburn University, and is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization.

Help us improve.