A new study finds the Sun passed within ~30 light-years of two luminous stars, Beta and Epsilon Canis Majoris, about 4.5 million years ago. Their intense ultraviolet radiation likely ionized the local interstellar medium up to ~100 times current levels and preferentially stripped electrons from helium, explaining an observed helium-ionization excess. Researchers used Hipparcos stellar motions, improved ultraviolet/X-ray data, and modern stellar-atmosphere models. The Sun may exit the protective local clouds in thousands to tens of thousands of years, with potential effects on cosmic-ray shielding.

Irradiated 'Scar' in Our Galactic Neighborhood Traces Back to Two Stars That Nearly Brushed Past the Sun

About 4.5 million years ago the Sun passed unusually close to two very luminous blue-white stars whose intense ultraviolet radiation left a faint but long-lived imprint — an irradiated "scar" — in the gas surrounding our solar system, according to a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal.

How the Scar Was Made

A research team led by University of Colorado Boulder astrophysicist Michael Shull used stellar-motion reconstructions to trace two hot stars, Beta Canis Majoris and Epsilon Canis Majoris, back in time. Their models indicate these stars came within roughly 30 light-years of the Sun about 4.5 million years ago and bathed the nearby interstellar medium in ultraviolet light up to ~100 times stronger than present levels.

Why This Explains a Long-Standing Puzzle

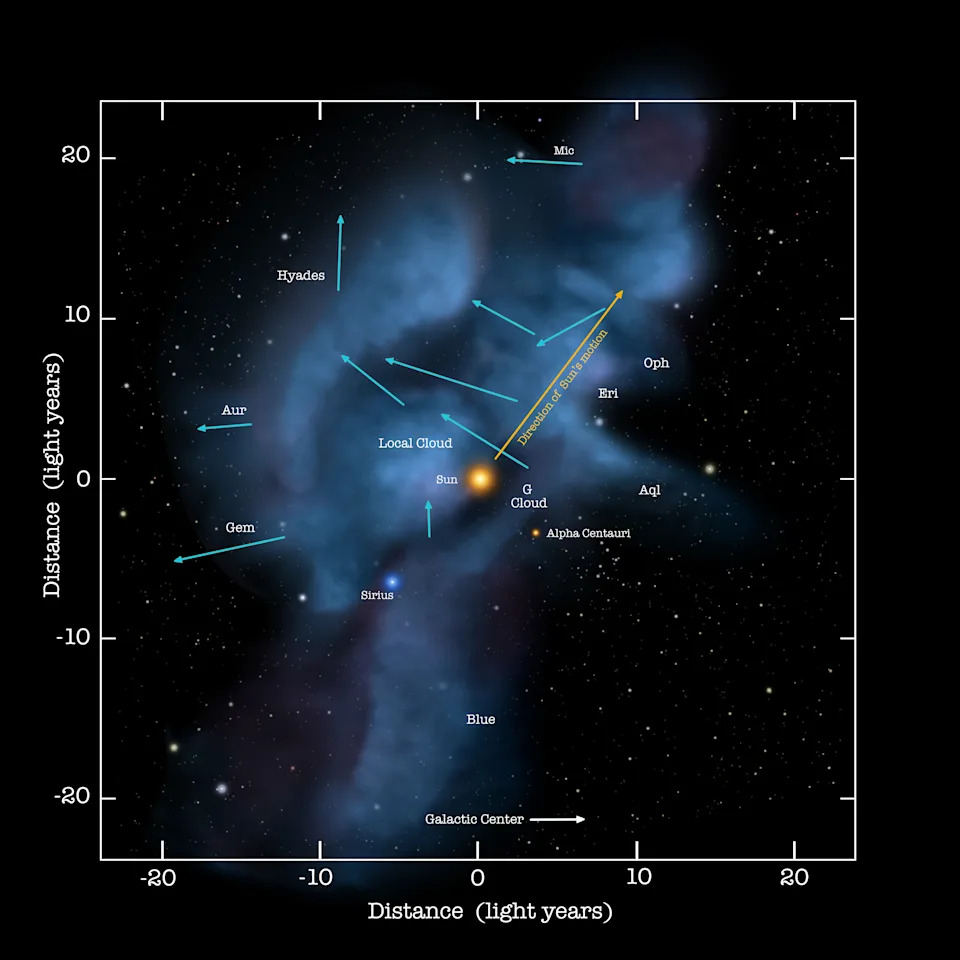

For decades astronomers have observed that the local interstellar medium (the diffuse patchwork of gas and dust extending about 30 light-years from the Sun) is more highly ionized than expected. In particular, helium atoms there are missing electrons at nearly twice the rate predicted relative to hydrogen. Because helium requires far more energetic photons to ionize than hydrogen, the Sun alone could not account for the discrepancy.

The study shows that the ultraviolet output of Beta and Epsilon Canis Majoris would preferentially strip electrons from helium, producing the observed helium excess. After the stars moved away, the gas began a slow process of recombination — free electrons reattaching to ions — but that recovery can take millions of years, leaving a lingering partial ionization that astronomers can still detect today.

"It’s like a dance floor — you’ve got protons and electrons dancing around," Shull told Live Science. "Sometimes they’re dancing together and sometimes they’re popping apart."

Tools and Evidence

The team relied on precise positions and motions from ESA's Hipparcos mission, stellar-atmosphere and evolution models, and improved ultraviolet and X-ray observations (including suborbital rocket flights) to estimate the stars' past brightness and trajectories. Although Beta and Epsilon now sit more than 400 light-years away in the Canis Major constellation, their young, hotter stages during the close passage produced the intense radiation responsible for the ionization.

Other ionizing contributors include three nearby white dwarfs (G191-B2B, Feige 24 and HZ 43A) and the larger Local Bubble — a cavity of supernova-heated gas extending roughly 1,000 light-years — but none alone explained the helium imbalance until the close pass of these two massive stars was taken into account.

Implications for Earth and Future Work

The local clouds that were ionized also act as a partial shield against high-energy charged particles (cosmic rays) that roam the galaxy. Models suggest the Sun could leave this protective patch in as little as ~2,000 years or within a few tens of thousands of years, which might alter the level of galactic radiation reaching Earth and have implications for the atmosphere, including the ozone layer.

Shull and colleagues emphasize that while this explanation brings researchers significantly closer to resolving the helium-ionization mystery, details remain to be refined: how ionization varied during the encounter, exact recombination timescales in different cloud regions, and the combined effects of other radiation sources.

Publication: The findings appeared Nov. 24 in The Astrophysical Journal.