ALMA and VLT/SPHERE combined to observe 57 molecular spectral lines around the red giant W Hydrae, 320 light‑years away, revealing a layered, turbulent atmosphere with clumps, arcs and plumes. The data show outward flows near the star (~22,400 mph / 36,000 km/h) and inward flows higher up (~29,000 mph / 46,000 km/h), matching 3D models of convective cells and shocks. Key molecules (SiO, H2O, AlO) align with newborn dust, linking chemistry to dust formation and improving our understanding of how evolved stars lose mass — a process that foreshadows the Sun’s eventual transformation into a red giant.

57 Molecular Views Reveal How a Dying Star Crafts Dust — A Preview Of the Sun’s Fate

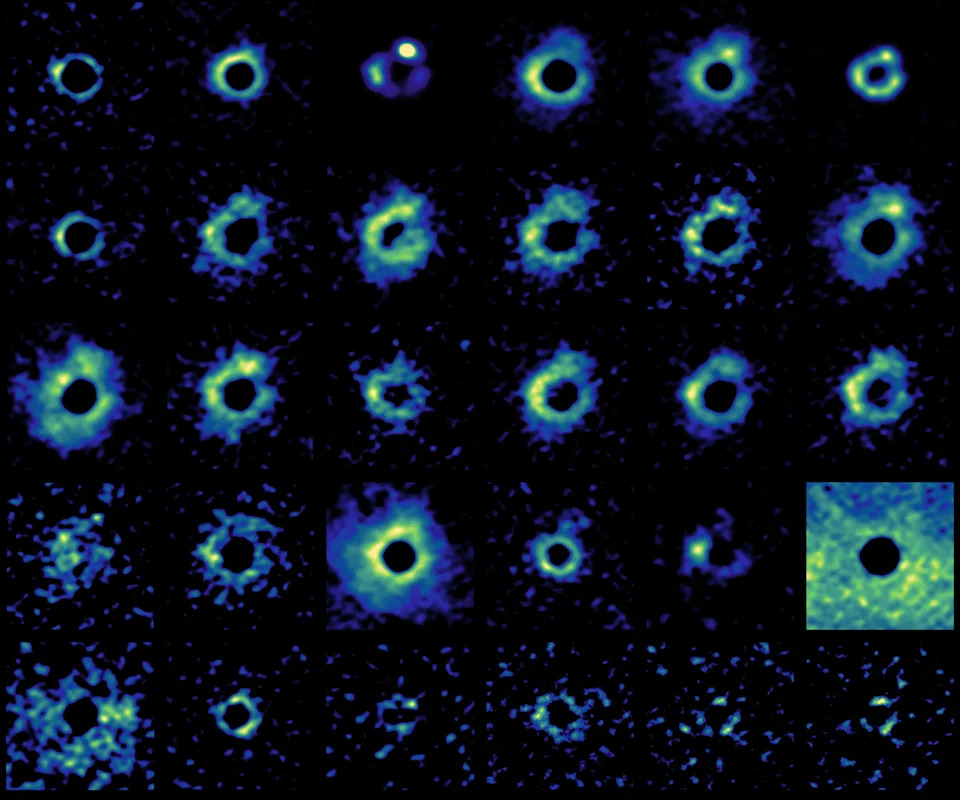

A team of astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Very Large Telescope’s SPHERE instrument to capture 57 distinct molecular “views” of the red giant W Hydrae, producing an unprecedented, multi-layered portrait of a star in its final stages. These observations reveal how shocks, pulsations and chemistry combine to form dust and drive mass loss in dying stars — processes that will one day shape the Sun’s fate.

Powerful Instruments, Unprecedented Detail

ALMA — an array of 66 radio antennas in northern Chile — mapped emission and absorption across 57 molecular spectral lines. Each spectral line acts like a chemical fingerprint, forming under specific physical conditions and exposing different layers of the star’s extended atmosphere. The array’s sensitivity is extraordinary: the team compares ALMA’s resolving power to photographing a grain of rice from about 6.2 miles (10 km) away.

Layers, Clumps and Dynamic Flows

The target, W Hydrae, is an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star located roughly 320 light‑years from Earth. Observations reveal clumps, arcs and plumes in the star’s envelope that appear differently depending on which molecule is observed. In some molecular tracers the star’s outer layers expand so far that, if W Hydrae were placed at the Sun’s position, those layers would reach beyond the orbit of Mars.

ALMA also tracked gas motions across these layers. Gas close to the stellar core is being driven outward at about 22,400 miles per hour (36,000 km/h), while gas in higher layers is observed falling inward at roughly 29,000 miles per hour (46,000 km/h). This alternating outflow/inflow pattern matches three‑dimensional models in which convective cells and pulsation‑driven shocks sculpt the atmosphere.

Linking Chemistry To Dust Formation

Because the ALMA and SPHERE observations were taken only nine days apart, the team could directly compare gas-phase molecules with newborn dust clouds seen in infrared images. They found that molecules such as silicon monoxide (SiO), water vapor (H2O) and aluminum monoxide (AlO) coincide spatially with clumpy dust clouds, strongly indicating these species participate in initial dust grain formation.

"With ALMA, we can now see the atmosphere of a dying star with a level of clarity in a similar way to what we do for the Sun, but through dozens of different molecular views," said Keiichi Ohnaka (Universidad Andrés Bello). "Each molecule reveals a different face of W Hydrae, revealing a surprisingly dynamic and complex environment."

The team also observed overlap between dust and other molecules — sulfur monoxide (SO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), titanium oxide (TiO) and possibly titanium dioxide (TiO2) — suggesting these species may contribute to dust production through shock‑driven chemistry. By contrast, hydrogen cyanide (HCN) forms close to the star but does not appear to participate directly in dust grain formation.

Implications For Stellar Evolution And Our Solar Future

As AGB stars shed their outer layers, they seed the interstellar medium with molecules and dust that become raw material for future stars and planets. Understanding where and how this mass loss begins addresses one of stellar astrophysics’ longest‑standing puzzles. W Hydrae provides a rare, spatially resolved laboratory to test and refine 3D models of convection, shocks and chemistry.

These observations also offer a preview of the Sun’s distant future: in roughly 5 billion years the Sun will swell into a red giant and undergo similar processes that will reshape the inner solar system. The team’s results were published on Dec. 2 in Astronomy & Astrophysics.