The chance of keeping global warming below 1.5°C is now slim: current trends point toward an overshoot this decade. That increases the risk of more frequent and severe heat waves, sea‑level rise, droughts, floods and possible ecological tipping points. Research into the social, political and economic consequences of a post‑1.5°C world is limited, so urgent adaptation planning is needed. At the same time, rapid growth in wind, solar and battery storage offers a practical, cost‑effective path to limit further warming — and every fraction of a degree avoided still matters.

We’re Likely to Breach 1.5°C — Not Doomed, But Now We Must Adapt and Accelerate Clean Energy

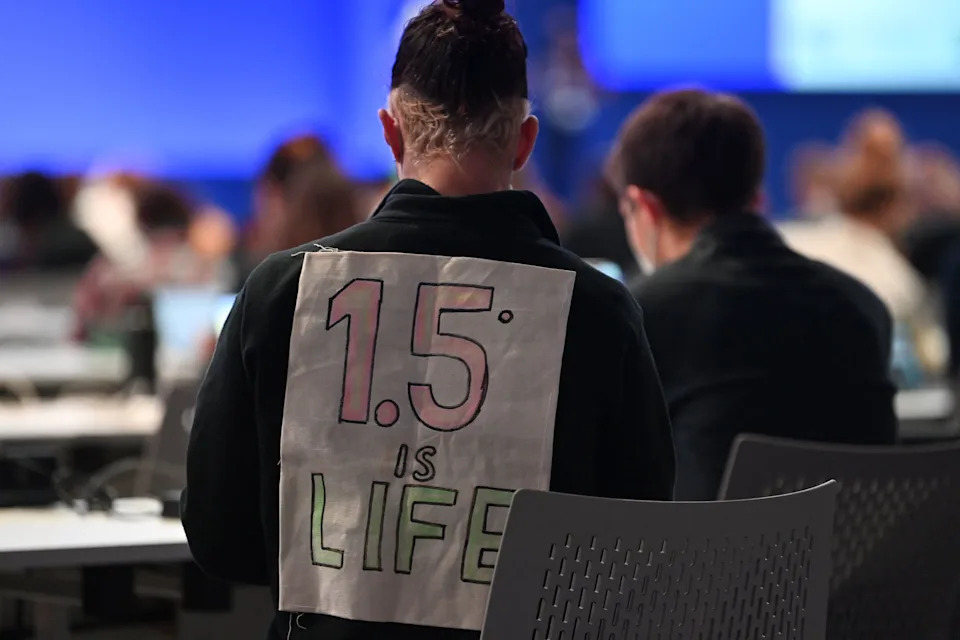

For the past decade, international climate efforts centered on a single benchmark: keeping global warming below 1.5°C (about 2.7°F) above pre‑industrial temperatures. That goal was meant to keep many of the most damaging impacts of climate change within a range societies could manage. This year made it increasingly clear that the window to hold warming under 1.5°C has effectively closed.

What the Science and Forecasts Show

Although the growth rate of greenhouse gases has begun to level off in some regions, emissions would now have to fall at an extraordinarily rapid pace to prevent an overshoot of 1.5°C. The UN Environment Programme recently estimated that, under current policies and trends, the world is likely to overshoot the 1.5°C threshold within the next decade. Some of the same scientific teams that warned about this outcome still stress that every fraction of a degree avoided matters.

“Scientists tell us that a temporary overshoot above 1.5 degrees [Celsius] is now inevitable,” UN Secretary‑General António Guterres said. “And the path to a livable future gets steeper by the day.”

Impacts We Are Already Living With

Human activities have already warmed the planet by more than 2°F since the 1800s. The world has seen record heat, shrinking glaciers, higher seas and stronger coastal flooding: global average sea level is roughly nine inches higher than in the 19th century. In 2024 the planet recorded its warmest year on record, and 2025 is on track to be the second warmest. Heat waves, droughts, intense precipitation events and wildfire conditions are becoming more frequent and severe.

As global averages rise, regional extremes amplify disproportionately — polar and continental interior warming can be much greater than the global mean. There is also the growing risk that warming could trigger ecological “tipping points”: self‑reinforcing losses such as major ice‑sheet collapse or large‑scale forest dieback that would accelerate change beyond gradual warming alone.

Adaptation, Politics and the Missing Research

With an overshoot likely, adaptation is urgent. Yet there is surprisingly little research that systematically explores the social, economic and political consequences of a post‑1.5°C world. Questions about migration, food security, political stability, and the capacity of governments and aid systems to respond demand much more attention.

Some scenarios in IPCC reports show possible temporary overshoots followed by a return below 1.5°C, but achieving that would likely require large‑scale, expensive interventions—massive ecosystem restoration or carbon removal from the atmosphere—while societies simultaneously pay mounting bills for climate disasters. Political will, financing and technology deployment remain major uncertainties.

Mitigation Progress: Renewables, Economics and Divided Priorities

There is good news: wind, solar and battery storage are expanding quickly and in many places are already cheaper than fossil fuels. That economic shift strengthens the case for continued emissions cuts independent of temperature goals. Many policies and investments are beginning to decouple economic growth from greenhouse‑gas emissions.

At the same time, some high‑profile funders and governments are rebalancing priorities between mitigation and adaptation. While donors like Michael Bloomberg are investing heavily in methane detection and reduction, others emphasize resilience and improving living standards in a hotter world. Developing countries — which contributed least to historical emissions — are already experiencing severe impacts and often lack adequate finance and timely support, prompting some to argue for broader development finance, including energy choices that can spur growth.

Why Every Fraction Of A Degree Still Matters

Missing the 1.5°C target is not an excuse for despair. Every fraction of a degree avoided reduces heat‑related deaths, protects ecosystems, lowers the economic toll of disasters and keeps more futures open for vulnerable communities. Practical investments in clean energy, targeted adaptation, early warning systems and resilient infrastructure will save lives and money.

In short: we are likely to breach the 1.5°C threshold, but that outcome increases rather than eliminates the importance of action. Policymakers, businesses and communities must both accelerate mitigation where possible and urgently scale adaptation, research and finance to manage a warmer world.