The article recounts how the 1971 lawsuit PARC v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania challenged schools' practice of labeling children "ineducable," pushed states to stop funneling students into institutions, and helped create the Child Find duty that became central to the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). It describes Pennhurst's abusive, eugenic‑era origins and documents how community‑based services improved lives and lowered costs. The piece warns that recent federal staffing cuts, policy changes and harmful rhetoric could threaten those gains, underscoring the need for continued oversight and advocacy.

How One Lawsuit Broke the School‑to‑Asylum Pipeline — and Why Progress Remains Fragile

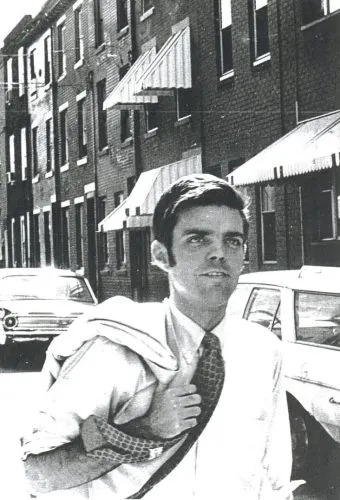

In 1969, two advocates from the Pennsylvania Association of Retarded Children (today the ARC of Pennsylvania) met a young lawyer named Thomas Gilhool. They handed him a report describing the appalling conditions at Pennhurst State School and Hospital — an overcrowded Pennsylvania asylum where children labeled "ineducable" were often consigned. Gilhool agreed to take a case that would not only challenge conditions at Pennhurst but also aim to stop schools from funneling children into institutions.

From School Exclusion To Institutionalization

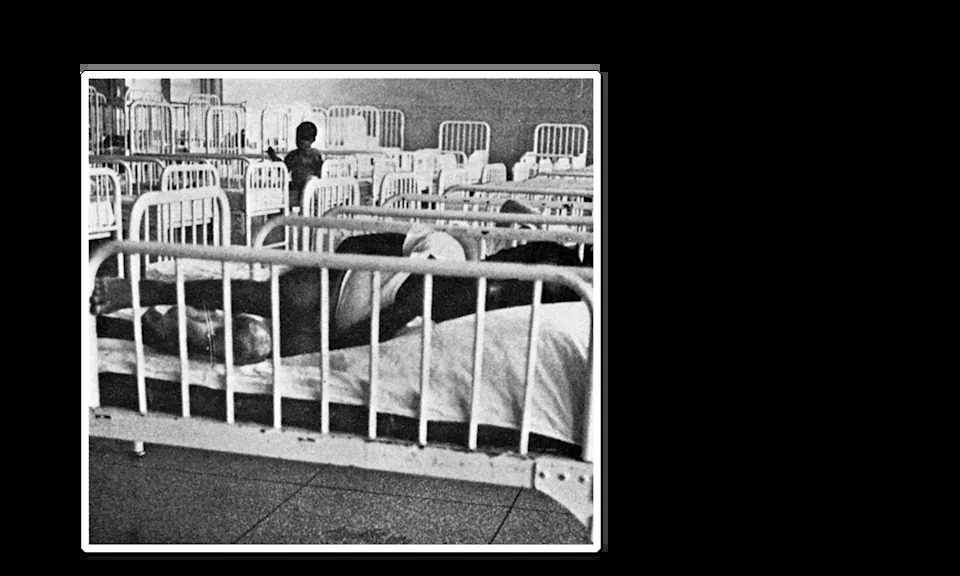

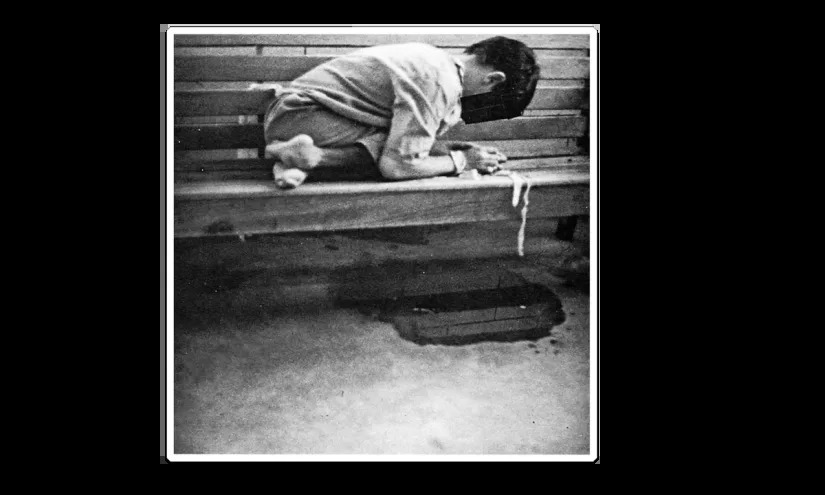

In the mid‑20th century, children could be labeled mentally retarded for many reasons: intellectual disability, seizure disorders, cerebral palsy, birth defects, behavioral differences, or even limited English. Public schools frequently served as the first stop on a short route to institutionalization. Students deemed "ineducable" were excluded from classrooms and often sent to institutions where neglect, abuse and forced labor were common.

Note on Language: The article describes historical usage of terminology that is now widely considered offensive. Quotes and contemporaneous language are preserved for historical accuracy and context.

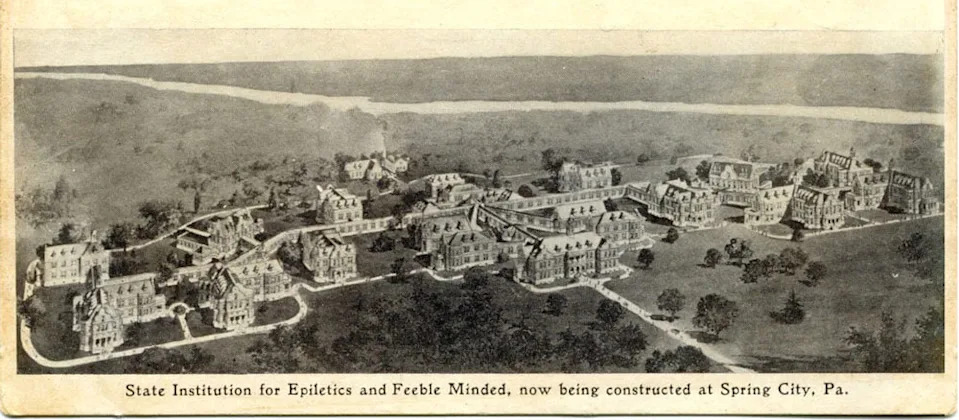

Pennhurst, Eugenics, And Public Outcry

Pennhurst was built in an era when eugenic ideas about disability, poverty and race influenced public policy. State laws and social attitudes sometimes supported institutional confinement and even sterilization. Reports given to Gilhool described residents "herded together to live as animals in a barn," facing forced labor, physical restraints and sexual abuse. Photographic exposés such as Burton Blatt and Fred Kaplan's Christmas in Purgatory helped galvanize public outrage.

“We have a situation that borders on a snake pit,” Robert F. Kennedy said after visiting Willowbrook — language that reflected and amplified a growing demand for reform.

PARC v. Commonwealth Of Pennsylvania

On Jan. 7, 1971, Gilhool filed a federal class‑action suit, PARC v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, backed by disability organizations. The complaint challenged school practices that labeled children ineducable and sought to guarantee their right to education. The case emphasized that denying education violated due process and equal protection under Brown v. Board of Education.

By October 1971, parties had negotiated a settlement requiring the state to identify, locate, evaluate and place children previously excluded from public schools. That settlement became a blueprint used in dozens of similar cases nationwide.

From PARC To IDEA: Creating Child Find And The IEP

The PARC settlement directly influenced federal action: the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA). IDEA guaranteed a free, appropriate public education, established the duty now known as Child Find (requiring schools to identify and evaluate students with suspected disabilities from birth through age 21), and codified the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process to specify supports and services.

Building Capacity And Changing Practice

Implementing IDEA required new expertise, teacher training and federal oversight. Educators like Linda Stevens and Pam Gillet canvassed communities to find students and convinced reluctant families to trust schools. Programs to train general educators and specialized staff proliferated, and federal monitoring pushed districts to build meaningful services. As classrooms and services expanded, many children who once would have been institutionalized were taught in public schools and supported in community settings.

Lives Changed — And The Ongoing Threats

Longitudinal research tracking 1,156 former Pennhurst residents found that people moved into the community were less likely to be homeless or jailed, lived on average six years longer than those who remained institutionalized, and cost about 15% less to serve in community settings. After Pennhurst closed, an estimated 150,000 people left institutions nationwide, and some estimates put the total number spared institutionalization since deinstitutionalization at roughly half a million.

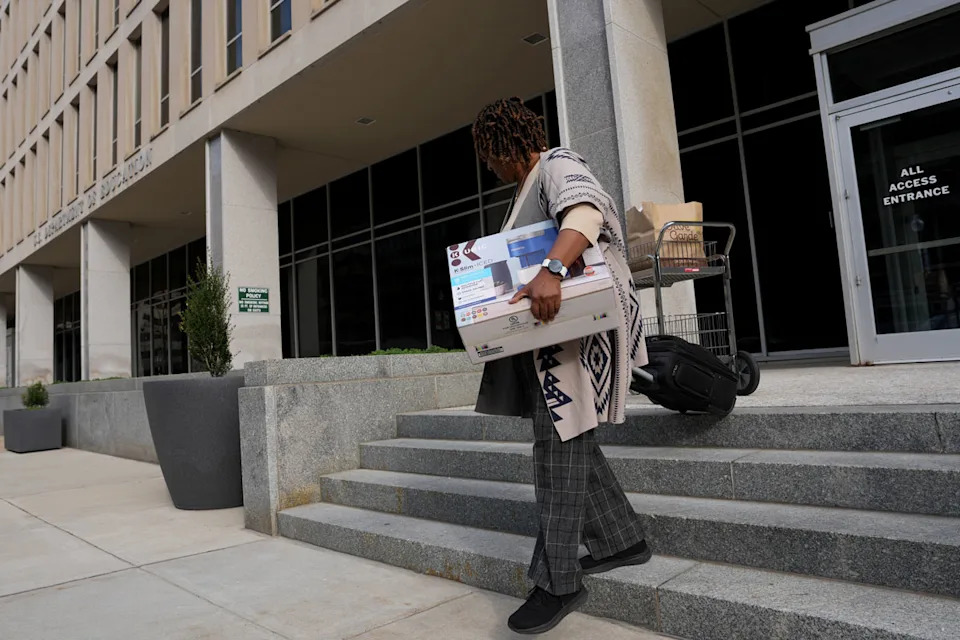

Yet the article warns that recent policy shifts, staff cuts and rhetoric at the federal level risk reversing gains. Proposals to shrink Education Department offices that enforce IDEA, changes at the Department of Health and Human Services, and demeaning or scientifically unsupported statements by senior officials raise alarms among advocates and legal scholars.

Pennhurst’s Later Years And Legacy

Pennhurst closed in 1987. Attempts to preserve it as a memorial and museum failed; the site was converted into a commercial haunted attraction that many disability advocates found disturbing. Still, the legal and social reforms launched by PARC and subsequent litigation reshaped education and civil rights for children with disabilities.

On a personal note, Bob Gilhool — the brother whose institutionalization helped galvanize his lawyer sibling — eventually lived independently. Tom Gilhool and others remember the litigation as transformational: it helped close Pennhurst and opened paths for countless children to access education and community life.

What This History Means Today

The story of PARC and IDEA is both a reminder of the harms institutionalization inflicted and a cautionary tale about fragile gains. Sustaining those gains requires funding, federal oversight, trained staff and public commitment — and legal vigilance when policies threaten to roll back civil rights protections for people with disabilities.