Utah researchers have identified a previously unknown nematode species in the Great Salt Lake, named Diplolaimelloides wo'aabi in consultation with the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. The tiny worm, under 1.5 mm, belongs to a genus usually found in coastal marine environments and shows traits not seen among over 250,000 described nematode species. Scientists say the species is adapted to hypersaline microbialites and could serve as a bioindicator, and they propose two origin theories: an ancient seaway relic or bird-mediated introduction.

New Nematode Species Discovered in Great Salt Lake — Named to Honor Shoshone Heritage

Researchers in Utah have confirmed a previously undocumented nematode species living in the hypersaline waters of the Great Salt Lake and named it Diplolaimelloides wo'aabi. The discovery, published in the Journal of Nematology, builds on earlier work by University of Utah scientists who established that nematodes inhabit the lake.

Details of the Discovery

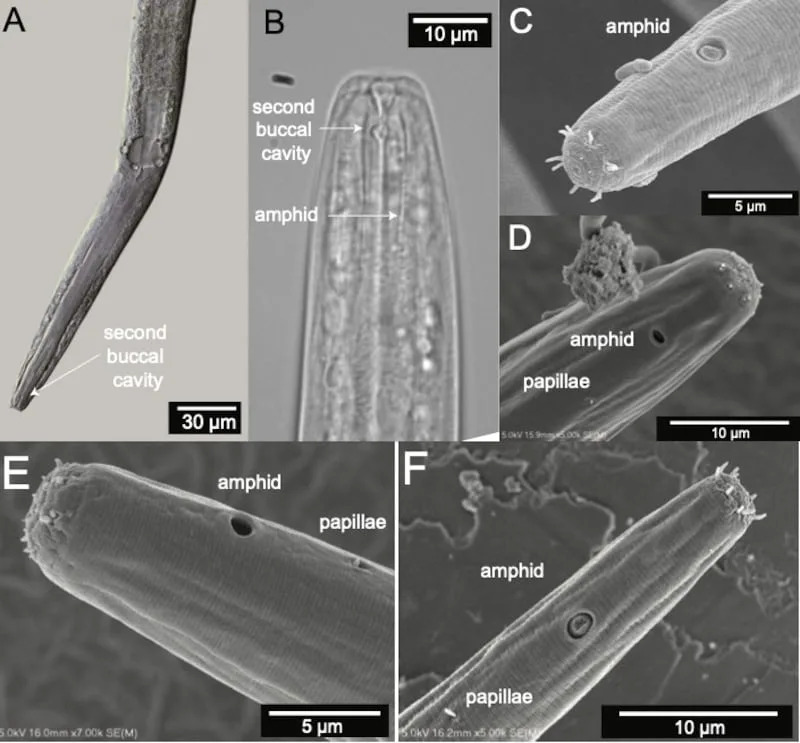

The newly described worm is under 1.5 millimeters long and belongs to the genus Diplolaimelloides, a group typically associated with coastal, saltwater habitats. Genetic analysis revealed at least two distinct nematode populations in the lake; one of these shows features not seen among the more than 250,000 named nematode species worldwide, making it an unusual inland representative of a primarily marine genus.

"It’s hard to tell distinguishing characteristics, but — genetically — we can see that there are at least two populations out there," said Michael Werner, assistant professor of biology at the University of Utah.

Naming and Tribal Consultation

Because the Great Salt Lake sits on ancestral land of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, researchers consulted tribal leaders about naming the species. Tribal representatives selected the name wo'aabi, which means 'worm' in the Shoshone language; the research paper notes and acknowledges the tribe's role in that decision.

Ecological Significance

The lake was long thought to be inhabited mainly by brine shrimp and brine flies. The ecological role of Diplolaimelloides wo'aabi remains to be determined, but authors describe the species as "notable for its adaptation to hypersaline microbialites" and suggest it could serve as a potential bioindicator of environmental change in the Great Salt Lake.

How Did It Get There? Two Leading Theories

The research team offers two plausible explanations for the presence of a typically coastal genus in an inland saline lake. Byron Adams, a Brigham Young University professor and co-author on the paper, suggests these worms could be remnants of Utah's ancient seaway: when the Colorado Plateau rose and the Great Basin formed, populations of coastal-origin organisms may have become trapped and isolated.

The alternate hypothesis is more recent dispersal: migratory birds that travel between continents frequently visit saline lakes and could carry microscopic organisms on their feathers or feet. The authors say a South American saline-lake origin transported by birds is surprising but feasible.

"(It’s) kind of hard to believe, but it seems like it has to be one of those two," Werner said.

Future research will explore the worm's ecological relationships, its prevalence across the lake, and which origin scenario is more likely. The discovery underscores how even well-studied places can still yield unexpected biodiversity.