A Scientific Reports study reexamines Neanderthal remains from the Troisième caverne of Goyet (Belgium) and finds evidence that some individuals were deliberately targeted, killed and processed like animal prey. Combining ancient DNA, stable isotopes and bone metrics, researchers identified at least six Neanderthals — four adult/adolescent females and two juveniles — an atypical demographic skew. Systematic cut marks, impact fractures and marrow extraction, plus reuse of human bones as retouchers, point to episodes of nutritional exocannibalism around 41,000–45,000 years ago. The study raises the possibility of violent intergroup conflict but does not identify specific perpetrators.

Study Suggests Neanderthals Were Selectively Targeted for Cannibalism at Goyet Cave

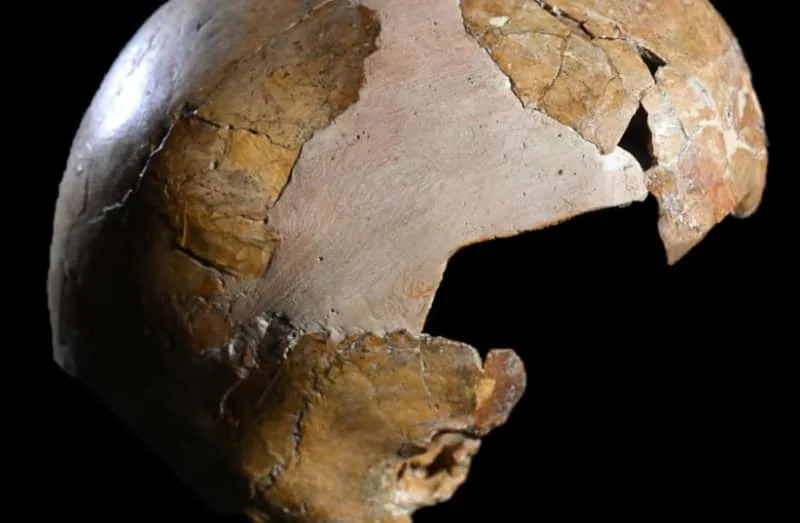

A new study published in Scientific Reports presents evidence that some Neanderthals from the Troisième caverne of Goyet (Belgium) were deliberately selected, killed and processed like animal prey. The research combines ancient DNA, stable isotope data and detailed osteological analysis to build a more complete picture of who the victims were and how they were treated.

What the Researchers Did

The team reanalyzed one of the largest known Neanderthal bone assemblages in northern Europe using multiple lines of evidence: ancient DNA to determine biological relationships and sex, stable isotope analysis to assess geographic origins and mobility, and metric and structural measurements of long bones to infer body size and robustness.

Key Findings

Researchers identified at least six Neanderthal individuals in the Goyet assemblage: four adults or adolescents identified as female and two juveniles. The demographic profile is unusual: adult males are largely absent, while females and children dominate the sample. Osteological measurements indicate these females were relatively short and gracile compared with males in other Neanderthal populations. Markers usually associated with high mobility were largely absent, yet isotopes indicate these individuals were not local to the Goyet area.

Bone modification patterns strengthen the interpretation of deliberate selection and nutritional cannibalism. The human remains show systematic cut marks, impact fractures consistent with marrow extraction, and the same sequence of butchery observed on animal prey at the site. Several human bones were also reused as retouchers for working stone tools. “The processing of human remains followed the same patterns as prey animals,” the authors write, arguing for nutritional rather than ritual treatment.

Interpretation and Context

The authors interpret these patterns as episodes of exocannibalism — killing and consuming outsiders — likely the result of violent intergroup conflict. Possible drivers include territorial competition, population stress, and broader social instability during a period of major environmental and demographic change in Europe. The remains are dated to roughly 41,000–45,000 years ago, when Neanderthal populations were contracting and Homo sapiens were expanding across the continent.

Caveats and Broader Significance

The study does not identify the perpetrators; both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens could potentially have been responsible at different times. The authors emphasize caution: cannibalism appears in many human contexts — from survival to warfare to cultural practice — and is not by definition evidence of uniquely savage behavior. Still, the clear demographic selectivity and the treatment of bodies at Goyet add an important and unsettling dimension to our understanding of Late Pleistocene human conflict and social organization.

As museums and collections are reexamined with modern techniques, the authors suggest similar patterns may emerge at other Ice Age sites across Europe, inviting a reevaluation of violence, group boundaries and resource competition in deep prehistory.