Texas A&M researchers report a lab method that uses microscopic molybdenum disulfide "nanoflowers" to double mitochondrial production in stem cells, which then donate extra mitochondria to aging or damaged cells. The approach proved effective in cell cultures and aims to enter rat testing in January or February. Experts call the findings promising but stress that human safety, including long-term effects of molybdenum disulfide, must be established through further preclinical and clinical trials.

Scientists 'Supercharge' Stem Cells With Nanoflowers to Recharge Cellular Powerhouses

Aging shows up as wrinkles, thinning hair and slowed thinking — but it also occurs inside cells when their energy producers, the mitochondria, begin to fail. Researchers at Texas A&M University report a laboratory method that boosts mitochondria production in stem cells and enables those cells to donate extra mitochondria to aging or damaged cells, a step that could eventually inform treatments for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, muscular dystrophy and fatty liver disease.

What the team did

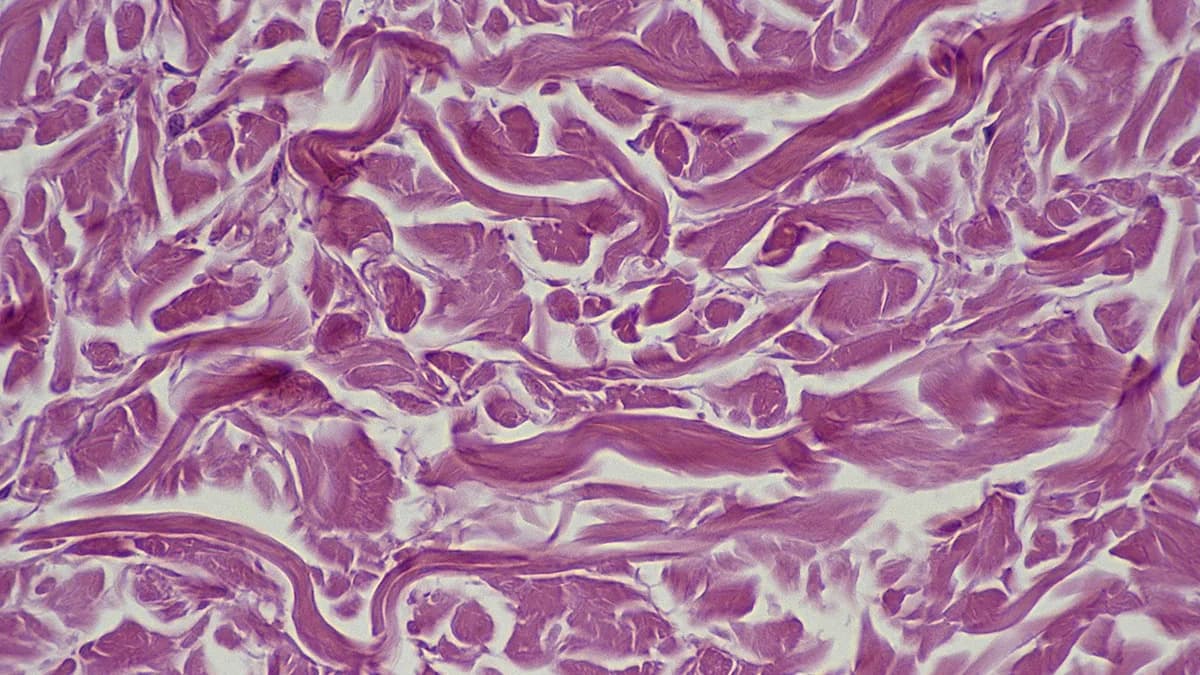

In experiments reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Akhilesh K. Gaharwar and colleagues added microscopic, flower-shaped particles — called "nanoflowers" — to cultures of stem cells. Made from the inorganic compound molybdenum disulfide, the nanoflowers are tiny (hundreds could fit across the width of a human hair) and enter stem cells through a natural uptake process.

Once inside, the nanoflowers stimulate the cellular pathways that drive mitochondrial biogenesis. In the lab, treated stem cells produced roughly twice the normal number of mitochondria and then transferred those extra mitochondria to neighboring aging or damaged cells.

Why this matters

Mitochondria are essential not only for energy production but also for immune responses and the synthesis of key molecules. Loss or dysfunction of mitochondria is implicated in many age-related and metabolic diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions and diabetes. Increasing the number and function of mitochondria in vulnerable cells could therefore have wide-reaching therapeutic benefits.

"We are supercharging stem cells so that they can donate these batteries to damaged cells at a much higher rate," said Gaharwar.

Expert reaction and caveats

Outside experts called the results promising. Daria Mochly-Rosen of Stanford said increasing mitochondria per cell is "huge," and noted the study underscores the potential for mitochondria-focused medicine. Keshav K. Singh cautioned that the research is early-stage and emphasized that the long-term safety of molybdenum disulfide in humans remains unknown.

Mochly-Rosen also raised an intriguing question: if nanoflowers are proven safe, could they be applied directly (for example, as an injection) to stimulate mitochondria growth locally without first reprogramming a patient’s cells? Determining how durable the benefit is will be crucial.

Next steps and potential applications

The Texas A&M team demonstrated the method in multiple cell types in laboratory dishes and aims to begin rat studies in January or February. If preclinical testing shows safety and efficacy, the approach could progress to human clinical trials. One envisioned pathway is autologous cell therapy: a patient’s skin cells could be reprogrammed into stem cells, treated with nanoflowers in the lab to boost mitochondria, and then returned to the patient to donate mitochondria to stressed or damaged tissues.

Potential clinical benefits include improved neuronal communication in aging nervous systems and better glucose handling in diabetes, among other possibilities. The lab is collaborating with groups focused on muscular dystrophy, fatty liver disease and nervous system disorders to explore these applications.

Bottom line: The nanoflower approach is an innovative proof of concept that boosts mitochondrial production in stem cells and promotes intercellular mitochondrial transfer in vitro. It is a promising direction, but substantial preclinical and clinical testing remains necessary — particularly to confirm the long-term safety of molybdenum disulfide and the duration of any therapeutic benefits.

Help us improve.