Using TESS data, astronomers identified ~130 planet candidates orbiting stars just beginning to swell into red giants (33 newly reported). The sample shows a steep drop in close‑in planets around expanding stars — a detected occurrence of about 0.11%, roughly 3 percentage points lower than for main‑sequence stars — implying many worlds are lost through tidal decay or engulfment. While Earth sits farther out and may avoid direct engulfment when the Sun becomes a red giant in ~5 billion years, habitability would almost certainly be destroyed.

Red Giants Are Devouring Nearby Planets More Often Than Thought — What That Means for Earth

Using TESS data, astronomers find that stars just entering the red giant phase destroy close-in planets far more efficiently than expected — with implications for the long‑term fate of the Solar System.

What the study found

Researchers used observations from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) to search for planets orbiting stars that are just beginning to expand into red giants. From an initial pool of nearly 500,000 light curves, the team narrowed the sample to roughly 15,000 candidate transit signals and applied an algorithm to isolate stars in the earliest stages of post‑main‑sequence evolution. That process produced about 130 planet candidates around these expanding stars, 33 of which are new detections.

Strong evidence of planetary loss

From this sample the team identified a clear deficit of close‑in planets around stars that have started to expand. The data indicate these expanding stars have only about a 0.11% chance of hosting a detected close‑in planet — roughly 3 percentage points lower than comparable main‑sequence stars. The occurrence of large, Jupiter‑ or Saturn‑like planets also falls as the host stars move further into the post‑main‑sequence.

"This provides strong evidence that as stars evolve off the main sequence they can rapidly force planets to spiral inward and be consumed," said Edward Bryant (University of Warwick). "Theoretical work has long suggested this, but now we can directly observe the effect across a sizeable population and measure how efficient these stars are at engulfing nearby planets."

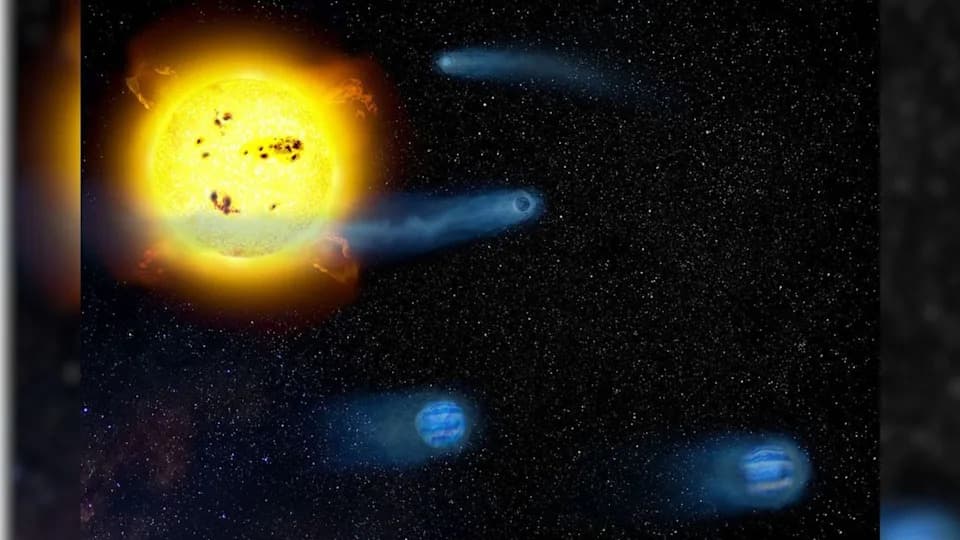

How planets are lost

There are two principal destructive mechanisms. First, physical engulfment can occur when a star expands enough to physically reach a planet's orbit. Second, tidal interactions — the gravitational tug‑of‑war between the star and a planet — transfer angular momentum and cause the planet's orbit to decay. As the star swells, tidal forces strengthen and can make a close planet spiral inward until it disintegrates or falls into the star.

Implications for Earth

Models suggest the Sun will become a red giant in roughly 5 billion years and likely engulf Mercury and Venus; whether it reaches Earth's orbit remains uncertain. The study focused on the earliest one to two million years of the post‑main‑sequence stage, so it captures only the initial phase of stellar expansion. "Earth is certainly in a different position than the giant planets in our study, which orbit much closer to their stars," said Vincent Van Eylen (University College London). "Earth might survive direct engulfment, but the conditions required for life would almost certainly be destroyed."

Next steps

The researchers plan to obtain more observations, especially mass measurements for the candidate planets, which will help distinguish the relative contributions of tidal decay versus direct engulfment. The study appears in the October issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Help us improve.