Researchers described a deep‑sea anemone, Paracalliactis tsukisome, living on shells of the hermit crab Oncopagurus monstrosus at 650–1,600 ft (≈200–490 m) off Japan’s Pacific coast. The anemone secretes a rigid carcinoecium that expands the crab’s living space, a rare capability for sea anemones. Study authors call the behavior “surprisingly sophisticated,” and note the anemone also feeds on the crab’s feces — a form of deep‑sea recycling that underscores a mutualistic, co‑evolved relationship.

Pale‑Pink Anemone Builds Extra Shell Space — and Recycles Hermit Crab Waste

Pale‑Pink Anemone Expands Shell Homes and Turns Waste into Food

Researchers working off Japan’s Pacific coast have described a deep‑water sea anemone that appears to live in close association with hermit crabs. The newly documented species, Paracalliactis tsukisome, was observed anchored to the shells of the hermit crab Oncopagurus monstrosus at depths of roughly 650–1,600 feet (about 200–490 meters).

The anemone secretes a shell‑like extension called a carcinoecium, effectively enlarging the usable shell area for its crab host. By building this rigid structure, the anemone gives the crab more living space and stability, a rare and surprising behavior for an animal group that normally lacks hard skeletons.

“Surprisingly sophisticated behavior” — Akihiro Yoshikawa, associate professor, Kumamoto University

Published in Royal Society Open Science, the study highlights both the structural innovation and the ecological benefits this relationship provides. In addition to creating extra living space, P. tsukisome appears to feed on the hermit crab’s feces — an efficient form of recycling on the deep‑sea floor that returns nutrients to the local food web.

The species name tsukisome comes from a classical Japanese word meaning “pale pink color,” and the authors note its poetic associations with a “deep, faithful bond.” The observation offers a rare window into a mutualistic, co‑evolved partnership between animals in the ocean’s depths, illustrating how seemingly simple organisms can develop complex, mutually beneficial behaviors.

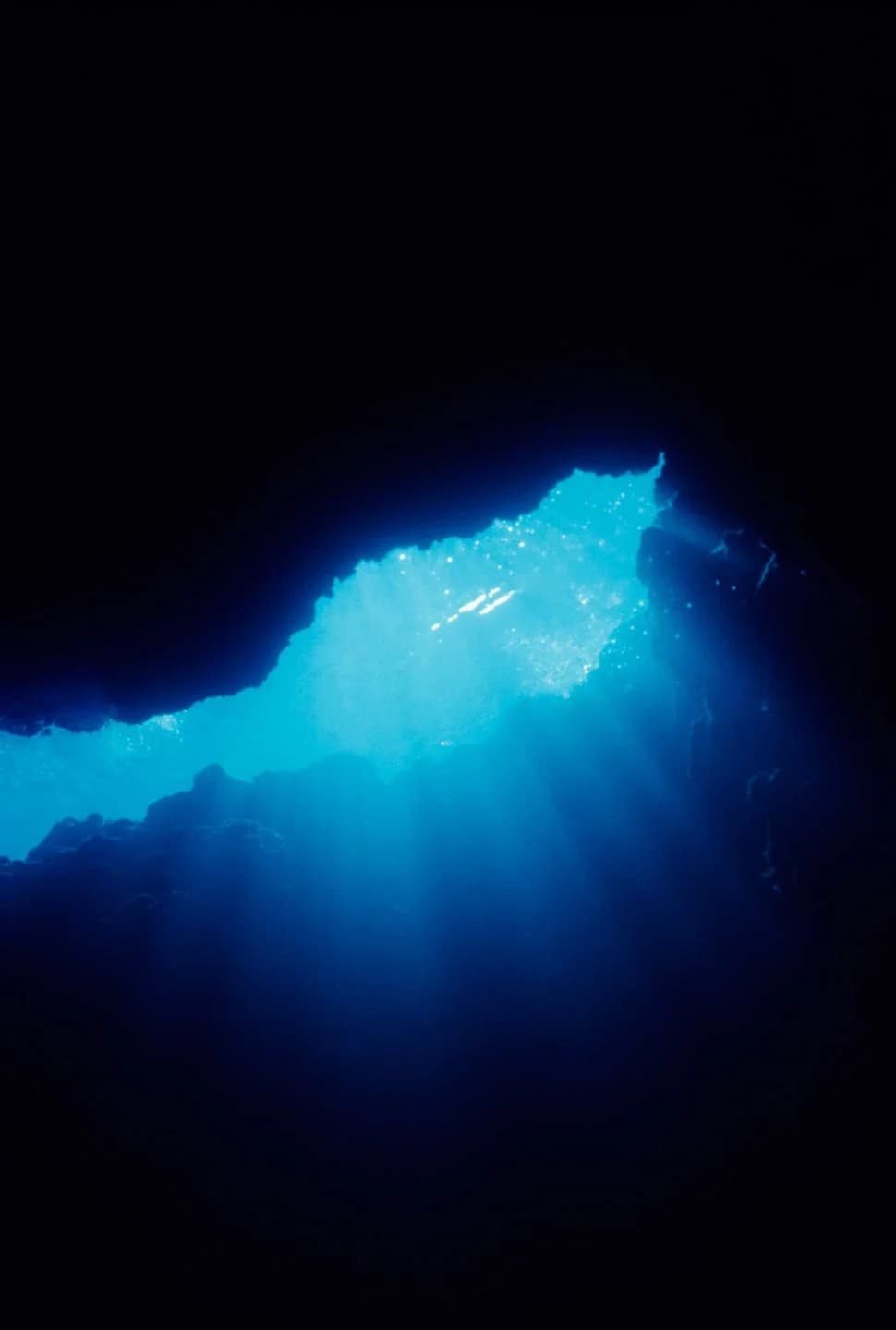

Lead image: Yoshigawa, A., et al. Royal Society Open Science (2025).

Help us improve.