New study: Archaeologists examined 16 ocher fragments from Crimea and northeastern Ukraine (dated ~100,000–33,000 years ago) and identified three Crimean pieces that appear to have been curated for repeated use. One fragment shows clear resharpening consistent with a fine-point tool used to make thin lines. While the authors suggest these could have functioned like crayons for body marking, notable experts caution that the wear and etchings might instead reflect pigment production or other practical uses, and no direct drawn marks were found. The dataset is small and the interpretation remains debated, but the finds broaden how researchers think about Neanderthal pigment use.

Sharpened Ocher 'Crayons' from Crimea Suggest Possible Neanderthal Body Marking

Neanderthals in Crimea crafted and maintained ocher "crayons," study suggests

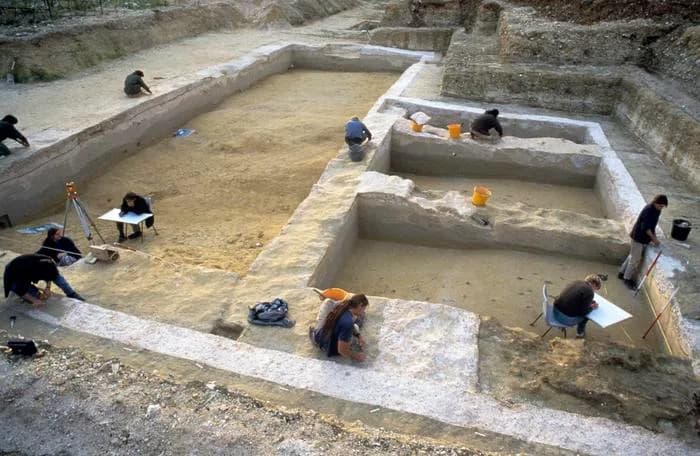

A new analysis of prehistoric pigment fragments suggests that some Neanderthals living in what is now Crimea fashioned red and yellow ocher pieces that resemble crayons — and at least one was repeatedly sharpened to a fine point. The research, published in Science Advances on Oct. 29, examined 16 ocher fragments from three Crimean rock shelters and a northeastern Ukrainian open-air site dated between roughly 100,000 and 33,000 years ago.

What the researchers found

Lead author Francesco d'Errico, a professor of archaeology at the University of Bergen, and colleagues inspected shapes, wear patterns and elemental composition to infer how each fragment had been worked and used. They identified three Crimean fragments that appear to have been curated for repeated use rather than consumed only as raw pigment for practical tasks.

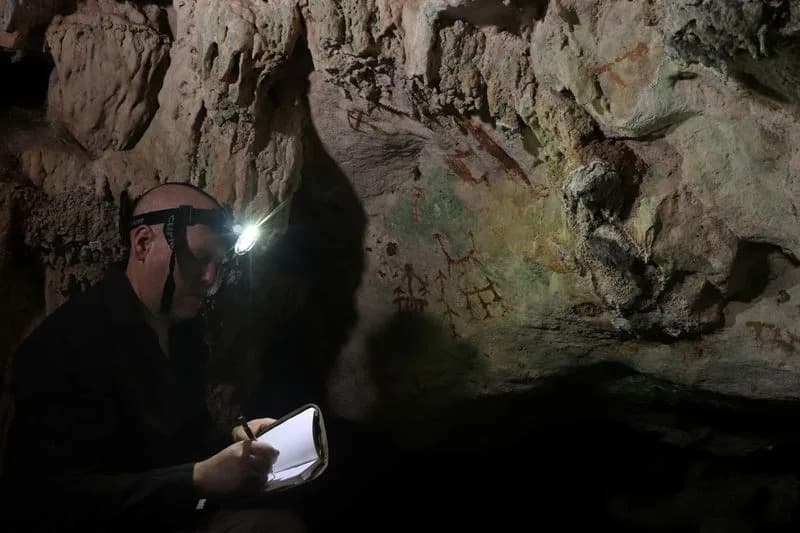

One fragment shows clear evidence of repeated scraping and grinding to maintain a sharpened tip, which the authors interpret as consistent with use like a coloured pencil or crayon for drawing thin lines on surfaces such as skin, stone or other objects. A second fragment resembles a broken crayon, and a third bears deliberate engraved lines at its base.

Interpretation and context

The authors argue that if ocher had been used primarily for practical tasks — for example, hide tanning, insect repellent, or powder production — there would have been little reason to maintain a fine point. The sharpened, curated nature of the pieces is therefore consistent with the possibility that they were used for socially meaningful activities, such as body marking or decoration.

"Finding a fragment where the tip was clearly resharpened was exciting," d'Errico said. "It shows the crayon was crafted and maintained for drawing fine lines. This is really something very special."

The study also traced the elemental composition of the ocher; some pieces appear to come from local outcrops while others originate from currently unidentified sources. The authors suggest that procurement choices could reveal how Neanderthals valued different colours or qualities of pigment, though they caution that the sample is small and conclusions about decision-making remain tentative.

Scholarly debate and caveats

Not all experts are convinced that the Crimean fragments demonstrate symbolic drawing. Rebecca Wragg Sykes (University of Cambridge) noted that the etchings and wear could reflect methods of producing powdered pigment rather than engraved motifs with symbolic meaning. She emphasized that such markings can be produced by functional processes and do not necessarily indicate symbolic intent.

April Nowell (University of Victoria) urged that researchers avoid a strict practical-vs-symbolic divide: once ocher was used for practical purposes, it could readily be adapted for social or aesthetic uses such as body painting or clothing decoration, as seen in many nonindustrialized societies.

Importantly, the Crimean fragments did not preserve any actual drawn marks that can be directly attributed to the sharpened tip. The findings expand the range of behaviors archaeologists must consider when interpreting pigment use by Neanderthals in Eastern Europe and western Asia, but they do not provide definitive proof of symbolic art.

Conclusion

The sharpened and curated ocher fragments from Crimea add intriguing evidence that Neanderthals sometimes prepared pigments in ways consistent with fine-line marking. However, the interpretation remains debated: alternative explanations (powder production, multifunctional use) are plausible, and the dataset is small. More finds and contextual information are needed to confirm whether these pieces were primarily cultural markers, multifunctional tools, or both.

Help us improve.