New analyses of caulking and a partial fingerprint from the Hjortspring canoe (c. 2,400 years old) point to an eastern Baltic origin. Chemical tests show the sealant was mainly animal fat mixed with pine pitch — a combination more likely sourced from pine-rich Baltic coasts than from Denmark or northern Germany at the time. Radiocarbon dates place the materials in the 4th–3rd centuries BC, and the evidence supports the idea of a planned seaborne raid on the island of Als. While not definitive, the results substantially strengthen the eastern-Baltic provenance hypothesis.

Partial Fingerprint on 2,400‑Year‑Old Hjortspring Canoe Points to Baltic Origin and Planned Seaborne Raid

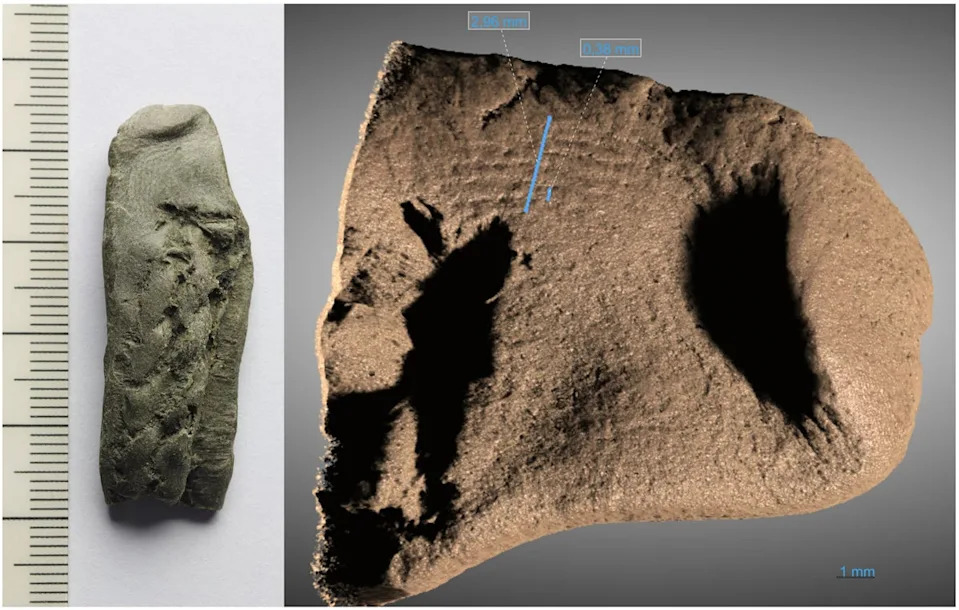

A partial fingerprint preserved on the caulking of Denmark’s ancient Hjortspring boat has provided a rare personal link to the people who built or used the plank canoe and offers a major new clue about the vessel’s origin.

New Analyses Reveal Material Origins

The wreck, discovered on the island of Als and first excavated in the early 1920s, is thought to have belonged to a vessel carrying roughly 80 people — widely interpreted as a warband. Researchers using modern chemical and radiocarbon techniques analyzed previously unstudied fragments of caulking and cordage recovered with the boat, plus a partial fingerprint impressed in the tar-like sealant.

Chemical analysis shows the sealing material was primarily animal fat mixed with pine pitch. Radiocarbon dating places these organic residues in the 4th–3rd centuries BC, consistent with earlier datings of the Hjortspring timbers and an age of about 2,400 years.

Why Pine Pitch Points East

The composition matters because extensive pine forests were scarce in Denmark and northern Germany during this period. The researchers argue that the pine pitch most likely originated from coastal areas to the east along the Baltic Sea, where pines were more abundant. If the materials were brought from the eastern Baltic, the boat and crew would have crossed a substantial stretch of open water to reach Als, implying the voyage — and the attack it supported — was planned and organized rather than opportunistic.

“Fingerprints like this one are extremely unusual for this time period,” the study authors note, highlighting how exceptional it is to find such a direct human trace in the tar used to waterproof the vessel.

Archaeological Context and Interpretation

For decades archaeologists have interpreted the Hjortspring find as the remains of an invading force defeated by local defenders. According to the prevailing interpretation, the victors sank the captured boat in a bog as a votive offering. The new chemical and fingerprint evidence does not overturn this scenario; instead, it refines the likely geographic origin of the craft and its occupants toward the eastern Baltic region.

The study, published in PLOS One, stresses that while the new evidence strengthens the eastern-Baltic hypothesis, it does not provide absolute certainty. The researchers call for broader sampling of comparable residues from other coastal sites to further refine understanding of seafaring networks and conflict in northern Europe during the 4th–3rd centuries BC.

Why This Matters

Beyond the geographic implication, the preserved fingerprint is archaeologically significant as a rare personal trace that connects us directly to an individual who handled the boat. Combined with the material evidence and dating, the find enriches our understanding of early Iron Age maritime mobility, craftsmanship, and organized warfare in the Baltic region.