Researchers from the University of York's Seeing the Dead project discovered fingerprints preserved in hardened gypsum casings from Roman-era burials in Yorkshire. The impressions — revealed after cleaning and 3D scanning a previously understudied 1870s sarcophagus — indicate the gypsum was smoothed by hand rather than only poured hot. At least 45 similar liquid-gypsum burials are known in the region. The team plans DNA tests at the Francis Crick Institute to try to learn more about who handled the dead.

Roman Handprints Found in Gypsum Casings Reveal Hands-On Burial Rituals in Yorkshire

About 1,800 years ago in Roman Britain, those preparing the dead in Yorkshire used a pourable gypsum paste that hardened into a plaster casing — and in at least one case they left behind clear fingerprints, researchers report.

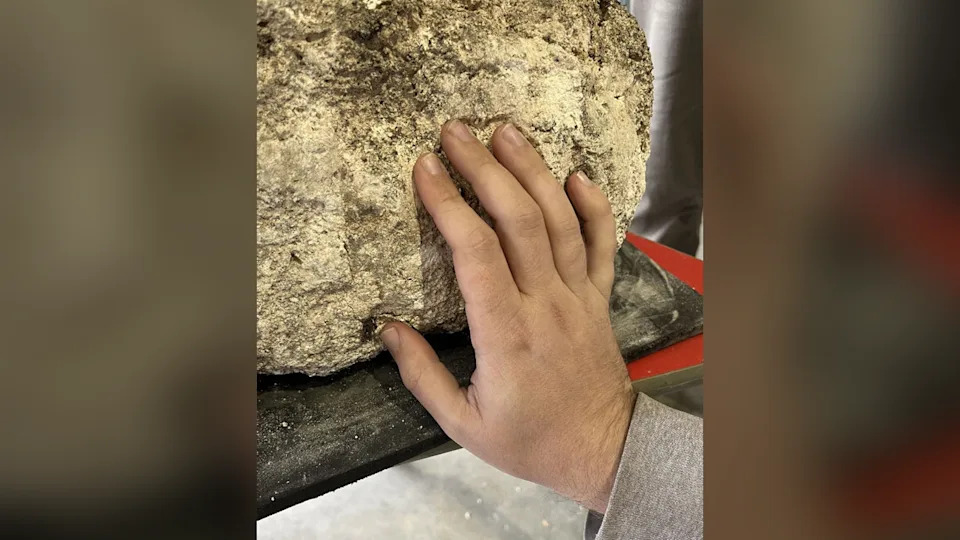

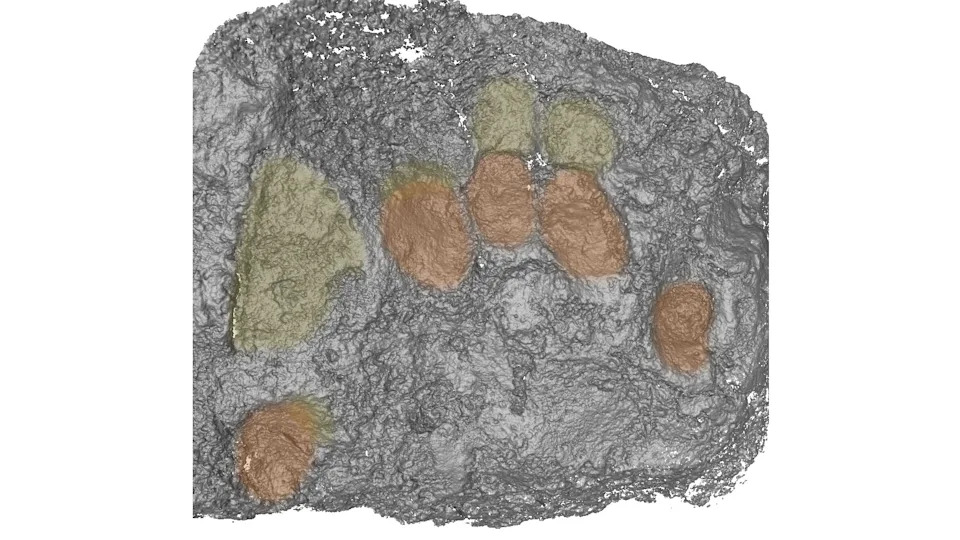

Archaeologists from the University of York's Seeing the Dead project examined a stone sarcophagus that had been unearthed in the 1870s but never fully studied. When the team removed and cleaned the internal gypsum casing, 3D scans revealed a surprising detail: impressions of human fingers and drag marks where someone had smoothed the material by hand.

What the gypsum tells us

Gypsum (the key ingredient in historic plaster and 'plaster of Paris') becomes a pourable liquid when heated and mixed with water, then hardens into a solid casing. Until now, researchers had assumed the mixture had been heated to roughly 300°F (150°C) and simply poured over the body. The presence of fingerprints indicates that, at least in this instance, the material was a softer paste that was spread and smoothed directly by human hands before it set.

'They had not been seen ever before,' said Maureen Carroll, a Roman archaeologist at the University of York and principal investigator for the Seeing the Dead project, describing the team's reaction when they first cleaned and 3D-scanned the casing.

So far, archaeologists have identified at least 45 liquid-gypsum burials in the Yorkshire region. The newly studied sarcophagus is notable because the gypsum reached close to the coffin edges, which hid the prints until the casing was removed for analysis.

Why this matters

The hand impressions supply a rare, intimate trace of contact between the living and the dead in Roman funerary practice. The marks could indicate whether a professional undertaker or a family member handled the final preparation, and they open the possibility of recovering biological traces.

The team plans to attempt DNA recovery from material associated with the handprint; samples will be analyzed at the Francis Crick Institute in London. While survival of DNA is uncertain, Carroll said that a best-case result would be inferring the genetic sex of the person who last touched the plaster — a finding that would be an important glimpse into who performed these rites.

Broader context

These discoveries add nuance to our understanding of regional funerary customs in third- and fourth-century A.D. Yorkshire, showing a hands-on approach to preparing the dead and demonstrating how modern techniques like 3D scanning can reveal details missed in earlier excavations.