Community leaders and public health officials say measles vaccination among Minnesota’s Somali children has fallen sharply amid persistent MMR-autism misinformation and growing fear of immigration enforcement. Coverage for Somali 2-year-olds declined from 92% in 2006 to about 24% today, far below the 95% needed to prevent outbreaks. Intermittent outreach and stalled in-person programs have weakened trust, though peer-led clinics and catch-up efforts have helped some families get vaccines by age six.

Fear, Misinformation and Enforcement Fears Drive Down Measles Vaccination in Minnesota’s Somali Community

Public health workers and Somali community leaders in Minneapolis warn that a long-running decline in measles vaccination has worsened as fear of immigration enforcement keeps families from seeking routine care. Persistent misinformation linking the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine to autism, intermittent outreach efforts and recent political developments have combined to leave many young children vulnerable.

Sharp Drop In Early Childhood Coverage

State data show a dramatic fall in early childhood coverage: in 2006, 92% of Somali 2-year-olds in Minnesota were up to date on measles vaccination; today that rate is roughly 24%. Public health experts say 95% coverage is needed to reliably prevent measles outbreaks, a disease that spreads extremely easily.

Why Trust And Access Have Eroded

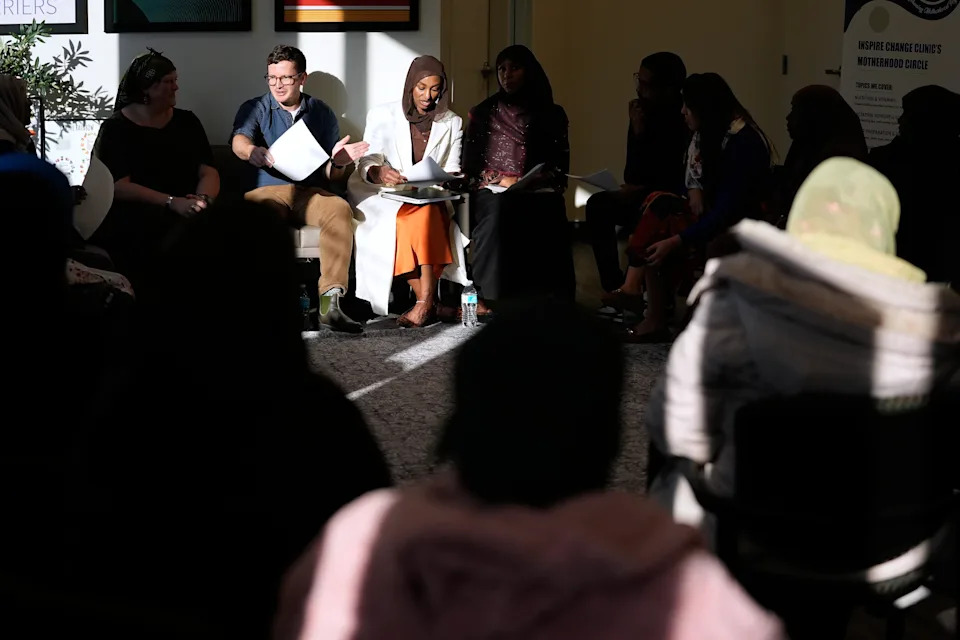

Community leaders say immigration enforcement measures have intensified fears that keep people at home and away from medical visits. "People are worried about survival," said nurse practitioner Munira Maalimisaq, CEO of Inspire Change Clinic. "Vaccines are the last thing on people’s minds." Motherhood Circle meetings and other in-person outreach have shifted online or paused, removing key opportunities to build trust.

Misinformation And Unanswered Questions

Researchers at the University of Minnesota reported estimated autism rates among Somali 4-year-olds are about 3.5 times those of white 4-year-olds, a disparity without a clear scientific explanation. In that informational vacuum, false beliefs have spread — notably that the MMR vaccine causes autism, a claim repeatedly disproven by research. Historical influences, including the now-discredited Wakefield study and later public comments suggesting unproven links, continue to fuel concern.

Local Efforts And Challenges

Public health teams have used trusted local partners, mobile clinics and peer-led programs to rebuild confidence. Inspire Change Clinic’s Motherhood Circles once saw success — one cohort reached 83% vaccination by the program’s end — and state efforts have helped many children catch up: while fewer than 1 in 4 Somali children receive measles vaccine by age 2, 86% have at least one MMR dose by age 6 (compared with 89% statewide).

But outreach has been inconsistent: federal funding cuts and stop-start initiatives have limited long-term impact. Community health educators emphasize that changing minds takes time: brief clinic appointments rarely suffice, and trust-building may require repeated conversations over months or years.

Risks And Next Steps

Clinicians worry most about unprotected young children, who face higher risks of severe complications such as pneumonia, brain swelling and blindness. Minnesota has experienced measles outbreaks in 2011, 2017, 2022 and 2024, and reported 26 cases last year across several communities with unvaccinated pockets. Local leaders and health officials say sustained, community-led outreach, stable funding and listening-first approaches are critical to restoring trust and raising vaccination rates.

“The misinformers will always fill the void,” said Mahdi Warsama of the Somali Parents Autism Network. “We need consistent, culturally grounded conversation and services to close that gap.”

Help us improve.