JWST observations of the protostar EC 53 in the Serpens Nebula show that crystalline silicates such as forsterite and enstatite form near young, hot stars and are then carried outward by episodic outflows. These ejected minerals can travel into the outer reaches of a system and become incorporated into comets that otherwise inhabit very cold regions. The result, reported in Nature, provides a clear explanation for a long-standing cometary mystery.

Webb Traces Comet Crystals Back to a Young Star — A Long-Standing Mystery Solved

New observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope are helping to explain why some of the solar system’s most distant comets contain crystalline silicates—minerals that form only at high temperatures. The crystals likely originated near young, hot stars and were later flung outward, eventually becoming incorporated into comets that live in the icy outskirts of planetary systems.

Young Stars Forge, Then Fling, Crystals

The team studied EC 53, a protostar forming in the Serpens Nebula about 1,300 light-years from Earth. EC 53 is surrounded by very hot dust and gas—conditions where silicate minerals such as forsterite and enstatite can crystallize. The protostar is variable: after roughly 18 months of relative calm it undergoes an accretion burst that lasts about 100 days, during which it rapidly pulls in nearby material while simultaneously driving layered outflows that push dust and debris outward along its protoplanetary disk.

Webb's MIRI Reveals the Dust's Journey

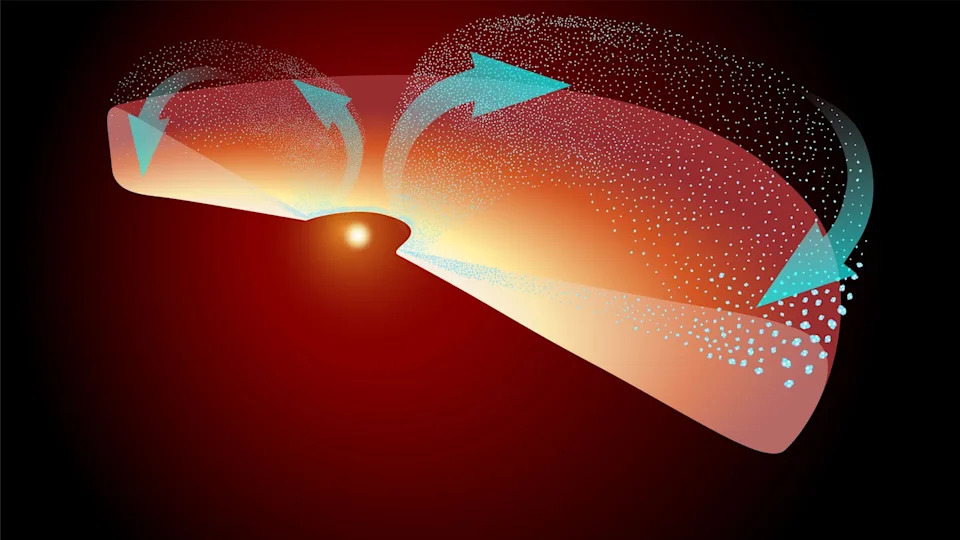

Using Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), astronomers mapped the composition and spatial distribution of dust around EC 53 during both quiet and active phases. They found crystalline silicates forming close to the protostar during bursts, then being carried outward by the star’s layered outflows. As co-author Jeong-Eun Lee of Seoul National University explained, “EC 53’s layered outflows may lift up these newly formed crystalline silicates and transfer them outward, like they’re on a cosmic highway.”

“Webb not only showed us exactly which types of silicates are in the dust near the star, but also where they are both before and during a burst.” — Jeong-Eun Lee, Seoul National University

Doug Johnstone, principal research officer at Canada’s National Research Council and co-author on the paper published in Nature, emphasized the significance: “Even as a scientist, it is amazing to me that we can find specific silicates in space, including forsterite and enstatite near EC 53. These are common minerals on Earth—the main ingredient of our planet is silicate.”

Implications for Comets and Planet Formation

The findings offer a plausible pathway for how high-temperature minerals end up in comets that spend most of their lives in frigid regions such as the Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt (where temperatures average about -450°F, roughly -269°C). The researchers estimate EC 53 will remain cloaked in its dust envelope for another ~100,000 years, during which time small rocks and debris will collide and coalesce into the seeds of future planets. Material launched outward by protostellar outflows could become incorporated into distant comets and planetesimals, transporting crystalline silicates from hot inner regions to cold outer reaches.

Bottom line: Webb’s MIRI has provided direct evidence that young, hot protostars can produce crystalline silicates and eject them into surrounding space—offering a compelling solution to why cold comets sometimes contain minerals that form only under high heat.

Help us improve.