Summary: A 2022 mouse study found that damage to the nasal epithelium may let Chlamydia pneumoniae travel along the olfactory nerve into the brain, prompting increased amyloid‑beta deposition — a protein associated with Alzheimer’s plaques. Infections occurred quickly (24–72 hours) and were worse when nasal tissue was injured. The findings are preliminary and limited to animals; human studies are needed to confirm whether this pathway contributes to Alzheimer’s disease.

Mouse Study Suggests Nose‑Picking That Damages Nasal Lining May Allow Bacteria To Trigger Alzheimer‑Like Brain Changes

A laboratory study published in 2022 found a plausible — though preliminary — link between damage to the nasal lining and dementia‑like brain changes in mice. The work raises questions about whether common behaviors that injure the nose could let bacteria reach the brain and provoke responses associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

What the Researchers Did

A team led by scientists at Griffith University in Australia used the bacterium Chlamydia pneumoniae, which can infect humans and cause respiratory illness, to test whether nasal injury could give microbes a route to the brain. In a mouse model, the researchers showed that C. pneumoniae can travel along the olfactory nerve — the pathway that links the nasal cavity to the brain — and that infections intensified when the nasal epithelium (the thin lining of the nose) was damaged.

Key Findings

- The bacteria reached the central nervous system rapidly, with infection evident within 24 to 72 hours in mice.

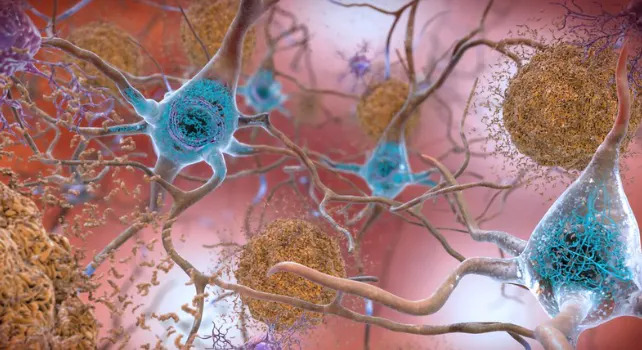

- Mice with nasal‑lining damage developed increased deposition of amyloid‑beta protein in the brain. Amyloid‑beta is produced during immune responses and is a major component of the plaques seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

- C. pneumoniae has also been detected in many human brains affected by late‑onset dementia, though its role in human disease remains unproven.

What This Does — And Does Not — Prove

The authors stress important limitations. The experiments were done in mice, and animal findings do not always translate to humans. It is also unresolved whether amyloid‑beta plaques cause Alzheimer’s disease, are a protective immune response, or are a byproduct of another process. The team calls for carefully designed human studies to test whether the same pathway operates in people.

“We’re the first to show that Chlamydia pneumoniae can go directly up the nose and into the brain where it can set off pathologies that look like Alzheimer’s disease,” said neuroscientist James St John of Griffith University when the results were published. He added that the evidence is "potentially scary for humans as well," but emphasized the need for human research.

Practical Takeaways

The study suggests a biological mechanism by which severe injury to the nasal lining could increase access for microbes to the brain. Because nose‑picking and plucking nostril hairs can damage the nasal epithelium, the researchers advise avoiding actions that injure the inside of the nose. However, routine nose‑picking without obvious injury has not been shown to cause dementia.

Next Steps

Follow‑up work is planned to examine whether the increased amyloid‑beta deposits are reversible once an infection is cleared and whether the mouse pathway exists in humans. A 2024 review further developed the hypothesis that nasal injury could increase Alzheimer’s risk and outlined additional ways the process might unfold, but direct human evidence is still lacking. The original mouse study appeared in the journal Scientific Reports.

Bottom line: The mouse study provides a biologically plausible link between damaged nasal tissue and Alzheimer‑like changes, but it does not prove causation in humans. Avoiding damage to the nasal lining is sensible precautionary advice while researchers investigate whether these findings apply to people.