Researchers from UTS and Auburn University identify five pathways by which microplastics may harm the brain, including weakening the blood–brain barrier, provoking inflammation, impairing mitochondria and injuring neurons. Although most ingested plastic is expelled, small particles can accumulate in organs and may drive chronic immune and oxidative stress. The study highlights possible but unproven links to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and calls for urgent further research while advising consumers to reduce everyday plastic exposure.

Could Microplastics Be Damaging Our Brains? Scientists Identify Five Possible Pathways

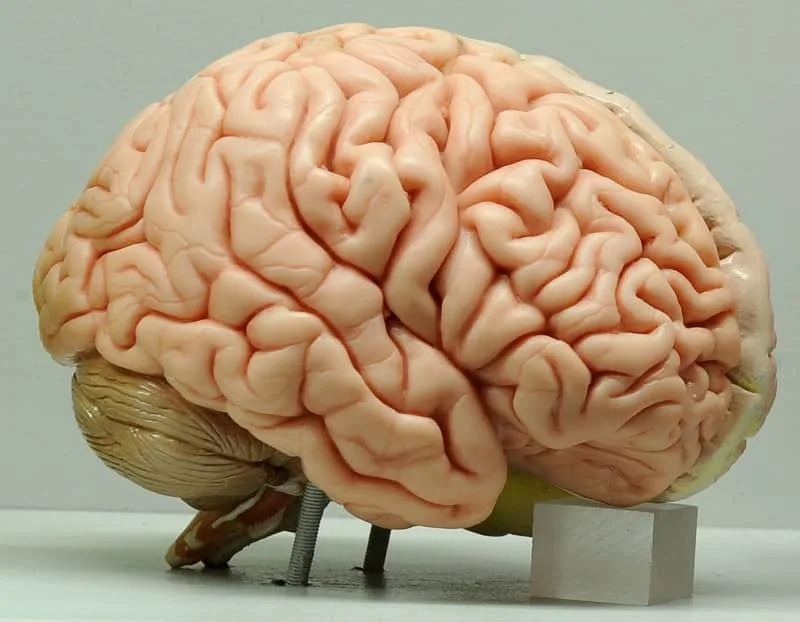

Nearly invisible and now widespread, tiny fragments of plastic that enter the body through food and air may be harming the brain in several ways, researchers warn. A team from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and Auburn University has outlined five main pathways by which microplastics—shed from water bottles, food containers, cutting boards and synthetic textiles—could damage neural tissue and potentially influence neurodegenerative disease.

What the Study Found

In a paper published in Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, the researchers report evidence that microplastics can:

- Weaken the blood–brain barrier, increasing its permeability;

- Trigger and dysregulate immune cell activity in the brain, promoting chronic inflammation;

- Cause oxidative stress and impair mitochondrial function, reducing cellular energy and resilience;

- Directly injure neurons and interfere with neuronal signaling;

- Accumulate in tissues and act as carriers for other pollutants or toxins.

How These Changes Could Matter

According to Kamal Dua of UTS, 'Microplastics actually weaken the blood–brain barrier, making it leaky. Once that happens, immune cells and inflammatory molecules are activated, which then causes even more damage to the barrier’s cells.' The study emphasizes that even though most ingested plastic is expelled, small particles can persist in organs and provoke sustained immune responses. When combined with other stressors—such as environmental toxins—these responses can lead to oxidative stress that harms neural tissue.

'When the brain is stressed by factors like toxins or environmental pollutants this also causes oxidative stress,'

One major concern, still unproven, is whether microplastics contribute to the accumulation of proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases—such as beta-amyloid and tau in Alzheimer's—or whether they accelerate neuronal damage relevant to Parkinson's disease. The authors stress that current evidence is suggestive but not yet definitive.

Advice and Next Steps

The paper concludes with a call for urgent, targeted research to clarify causal links between microplastic exposure and neurological outcomes, including long-term human and mechanistic studies. In practical terms, co-author Keshav Raj Paudel recommends simple exposure-reduction steps: avoid plastic containers and plastic cutting boards when possible, limit dryer use, choose natural rather than synthetic fibres, and reduce consumption of highly processed and packaged foods.

Policy and public-health implications: Because plastics are ubiquitous, the researchers argue that coordinated research, improved product standards, and public guidance could help determine risks and reduce avoidable exposures while scientists continue to investigate potential links to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases.