Venus looks exceptionally bright because it reflects most of the sunlight that hits it. Thick clouds of tiny sulfuric-acid droplets give Venus a high albedo (~0.76), scattering light efficiently. Its proximity to the Sun and to Earth boosts how much light we see, and orbital phases — particularly the crescent phase that produces a ‘glory’ scattering effect — create peaks in apparent brightness. Overall magnitude varies roughly from -4.92 to -2.98, keeping Venus visible much of the year.

Why Venus Shines So Bright: Clouds, Proximity, and the ‘Glory’ That Makes It Gleam

If you glance at the sky during a clear dawn or dusk, Venus is hard to miss: a steady, brilliant point of light that is second only to the Moon in apparent brightness. Astronomers measure Venus at about magnitude -4.14 on average, roughly 100 times brighter than a typical first-magnitude star.

What makes Venus so luminous? Several factors combine: an extremely reflective atmosphere, efficient scattering by tiny cloud droplets, and orbital geometry that often puts the planet close enough for us to see the reflected sunlight clearly.

High Albedo: Venus Reflects Most of the Sunlight It Receives

Venus has a very high albedo (reflectivity) of about 0.76, meaning it reflects roughly 76% of incoming sunlight back into space. For comparison, Earth reflects about 30% and the Moon only about 7%. That high reflectivity is the primary reason Venus appears so bright.

Clouds: A Thick, Light-Scattering Blanket

The planet is shrouded by dense cloud decks that extend roughly 48–70 km (30–43.5 miles) above the surface. These clouds and the hazes between them are made mostly of tiny sulfuric-acid droplets — typically microns in size — that scatter sunlight very efficiently. The result is a bright, uniform disk that sends a lot of light back toward space (and toward Earth).

Proximity and the Inverse-Square Law

Venus orbits closer to the Sun (about 0.72 AU, roughly 67 million miles or 108 million km) than Earth, so it intercepts more intense sunlight than more distant icy bodies. For example, Saturn’s moon Enceladus has an even higher albedo (~0.8) but appears much dimmer from Earth because it receives far less sunlight — the inverse-square law makes intensity fall off quickly with distance.

Distance From Earth and Phases Matter

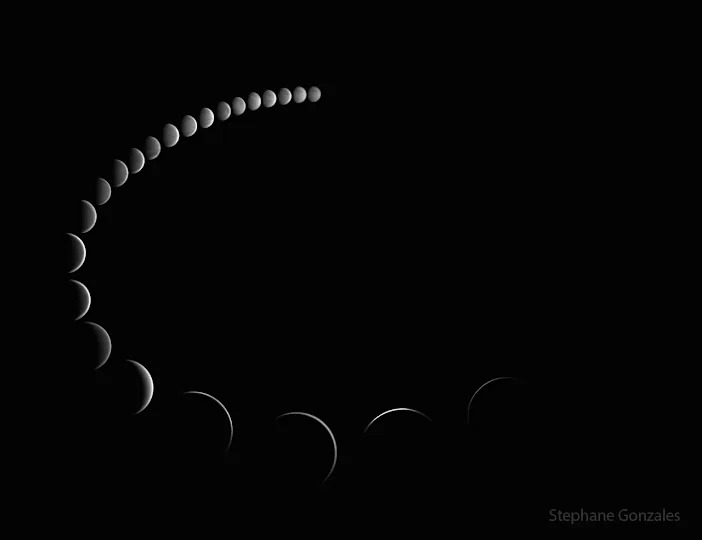

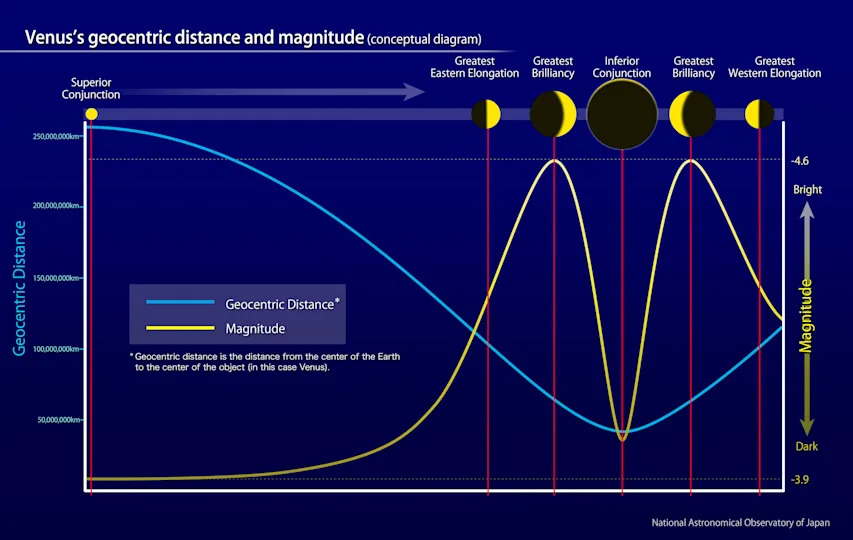

Earth’s view of Venus changes with the two planets’ orbits. Venus can come as close as about 38 million km (24 million miles) at inferior conjunction and be on the far side of the Sun at superior conjunction, when it is much more distant. The inner planets also display phases like the Moon’s: at inferior conjunction the bright hemisphere faces away from us, so Venus is dim, while at superior conjunction it appears small because it’s far away.

Why Venus Is Often Brightest As A Crescent

Counterintuitively, Venus reaches its greatest apparent brightness not when it looks full but when it appears as a bright crescent. This moment — called the point of greatest brilliancy — typically occurs about a month before and after inferior conjunction. Research suggests that sunlight scattered by the suspended sulfuric-acid droplets produces an optical scattering enhancement known as a glory, an effect related to rainbows that intensifies the crescent’s brightness.

How Bright Can Venus Get?

Combining changes in albedo, viewing geometry, and distance, Venus’ apparent magnitude ranges roughly from about -4.92 (very bright) to about -2.98 (still easily visible). Even at the dimmer end of that range, Venus remains one of the most prominent objects in the sky and can often be seen from light-polluted urban areas.

Bottom line: Venus’ extraordinary brightness is primarily due to its reflective, cloud-covered atmosphere and its relative closeness to both the Sun and Earth, with orbital phases and scattering effects like a glory modulating its peak brilliance.