Fundemar in Bayahibe, Dominican Republic, uses assisted coral fertilization — a lab-based method like in vitro fertilization — to produce genetically diverse coral recruits and restore degraded reefs. The laboratory produces more than 2.5 million embryos yearly; although survival in the ocean is low (about 1%), it can outpace natural fertilization on depleted reefs. Restoration helps protect fisheries, tourism and coastal defenses, but experts warn lasting recovery requires cutting greenhouse gas emissions and tackling local stressors.

Assisted Coral Fertilization Offers Hope for Vanishing Reefs in the Dominican Republic

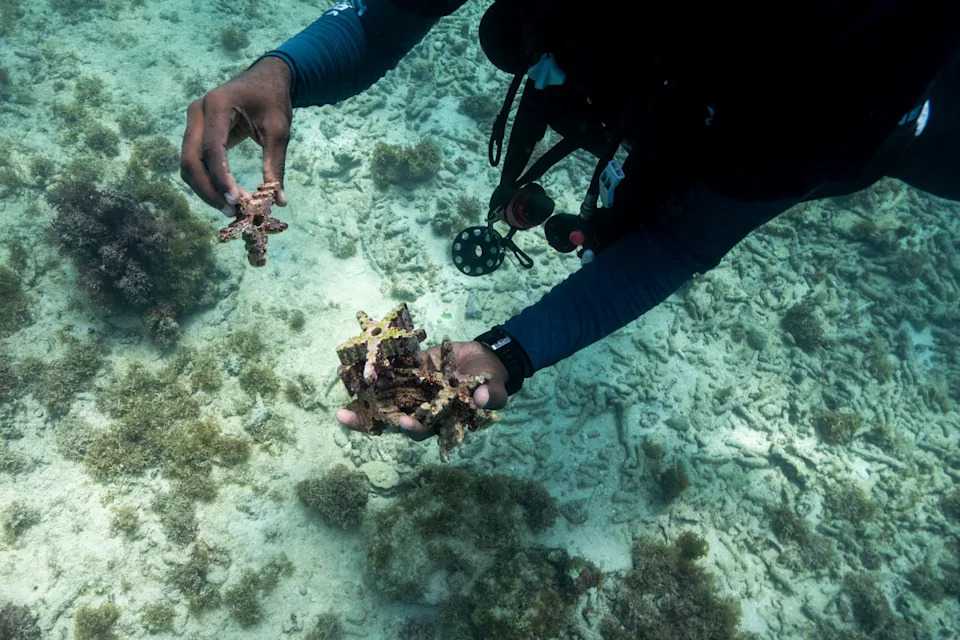

Oxygen tank on his back, conservationist Michael del Rosario finned gently through an underwater nursery off Bayahibe, Dominican Republic, pointing out “coral babies” taking hold on metal frames that look like giant spiders. These juvenile corals were conceived in an assisted reproduction laboratory run by the marine conservation group Fundemar and later grown in sea nurseries until they were ready to return to the reef.

The Technique: Lab-Based Fertilization

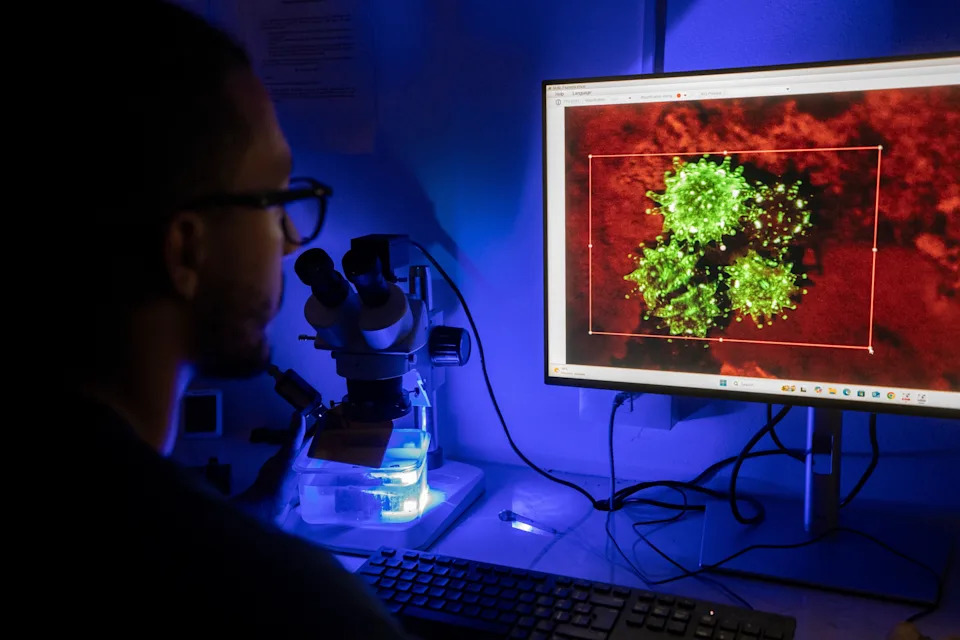

In a process similar to in vitro fertilization, researchers collect eggs and sperm during coral spawning events, combine them in the laboratory, and rear the resulting larvae in tanks until they are robust enough for transplantation. Fundemar’s lab produces more than 2.5 million coral embryos each year; while only about 1% are expected to survive once placed in the ocean, that survival rate can exceed what natural fertilization achieves on heavily degraded reefs.

Why It Matters

Climate change, warming seas and local pressures such as overfishing have left much of the Dominican Republic’s reefs in dire condition. Fundemar’s most recent monitoring found that roughly 70% of the country’s reefs now have less than 5% live coral cover. With healthy colonies increasingly isolated, the odds that eggs and sperm meet naturally during annual spawning events are declining — which is why assisted sexual reproduction is becoming more important.

“We live on an island. We depend entirely on coral reefs, and seeing them all disappear is really depressing,” del Rosario said. “But seeing our coral babies growing, alive, in the sea gives us hope.”

From Cloning To Genetic Diversity

Conservation groups earlier relied mainly on asexual propagation: cutting fragments from healthy corals and transplanting them to grow new colonies. That method can rapidly increase coral cover but produces clones with identical genetics, leaving restored populations vulnerable to the same diseases or stressors. Assisted sexual reproduction creates genetically diverse individuals, reducing the risk that a single pathogen or heat event could wipe out entire restored patches.

Australia pioneered assisted coral fertilization, and the approach is expanding across the Caribbean — with projects at institutions such as the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the Carmabi Foundation in Curaçao, and efforts in Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica.

The Bigger Threat: Warming Oceans

Experts warn that restoration work will be limited without action on the root cause: greenhouse-gas-driven climate change. Burning fossil fuels warms the atmosphere and the oceans; according to UNESCO’s most recent State of the Ocean report, oceans are warming at roughly twice the rate they did 20 years ago. Elevated temperatures cause corals to expel the symbiotic algae that provide their color and much of their energy, a process known as bleaching. Repeated or prolonged bleaching events weaken corals and increase mortality.

Research published in One Earth by the University of British Columbia estimates that roughly half of the world’s reefs have been lost since 1950.

People, Coasts And Fisheries At Stake

Healthy reefs protect coastlines by absorbing wave energy — a crucial function for nations in the hurricane corridor like the Dominican Republic. They also support fisheries and tourism. “What do we sell in the Dominican Republic? Beaches,” del Rosario said. “If we don’t have corals, we lose coastal protection, we lose the sand on our beaches, and we lose tourism.”

Local fishers feel the impacts firsthand. Fisherman Alido Luis Báez said he now travels up to 50 miles offshore to find tuna, dorado or marlin — a far cry from the 1970s when abundant coastal reefs yielded large catches closer to shore.

Scale, Hope And Limits

Del Rosario and Fundemar believe there is still time to slow or halt reef decline if restoration is scaled up and global emissions are reduced. “More needs to be done, of course…but we are investing a lot of effort and time to preserve what we love so much,” he said. Scientists and practitioners agree that restoration can buy time and expand genetic diversity on reefs, but long-term resilience depends on cutting global greenhouse gas emissions and addressing local stressors such as overfishing and pollution.

Key Facts: Fundemar produces ~2.5 million coral embryos annually; roughly 1% may survive in the wild after transplantation. About 70% of Dominican reefs now have under 5% coral cover.