A U‑M and MSU team used the CHARA Array at Mount Wilson to produce the highest-resolution images yet of nova eruptions. Published in Nature Astronomy, the study shows mass ejection can occur as multiple outflows and delayed expulsions rather than a single instant blast. The paper analyzes two 2021 novae — Nova Herculis 2021, which peaked within ~16 hours, and Nova Cassiopeiae 2021, which reached peak brightness about 53 days after discovery — improving our understanding of stellar explosions and mass transfer.

Highest-Resolution Images of Nova Explosions Reveal Complex, Delayed Mass Ejections

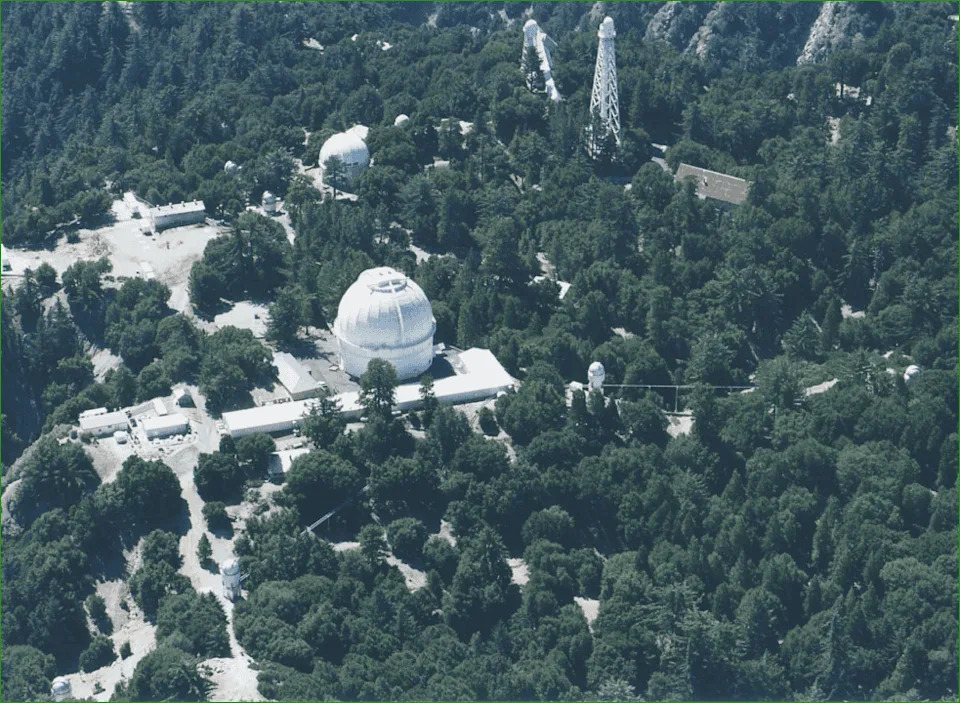

A team of astronomers from Michigan State University (MSU) and the University of Michigan (U‑M) used Georgia State University's CHARA Array at Mount Wilson Observatory to capture the highest-resolution images yet of novae — bright eruptions that occur on the surfaces of white dwarf stars. Their results, published in Nature Astronomy, show that mass ejection in novae can occur in multiple outflows and with delayed expulsions rather than as a single instantaneous blast.

What Is a Nova?

A nova occurs in a binary system when a dense white dwarf star pulls hydrogen-rich material from a nearby companion. As that material accumulates on the white dwarf's surface, it can ignite in runaway thermonuclear fusion, producing a sudden bright outburst and expelling material into space. While most white dwarfs are faint and slowly cool over time, accreting systems can produce these dramatic, sometimes recurring explosions.

"It's basically just a dense core of often carbon and oxygen — you can almost imagine like a huge diamond in the sky," said Laura Chomiuk, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State.

How the Team Observed the Explosions

Researchers led by Laura Chomiuk and John Monnier observed two 2021 novae with the CHARA interferometric array operated by Georgia State University at Mount Wilson in Southern California. Monnier's group contributed key hardware and software needed to produce the high-resolution images. Such bright novae suitable for detailed imaging are rare — fewer than one per year — so the team relies on rapid alerts and quick-response observing campaigns.

Key Findings

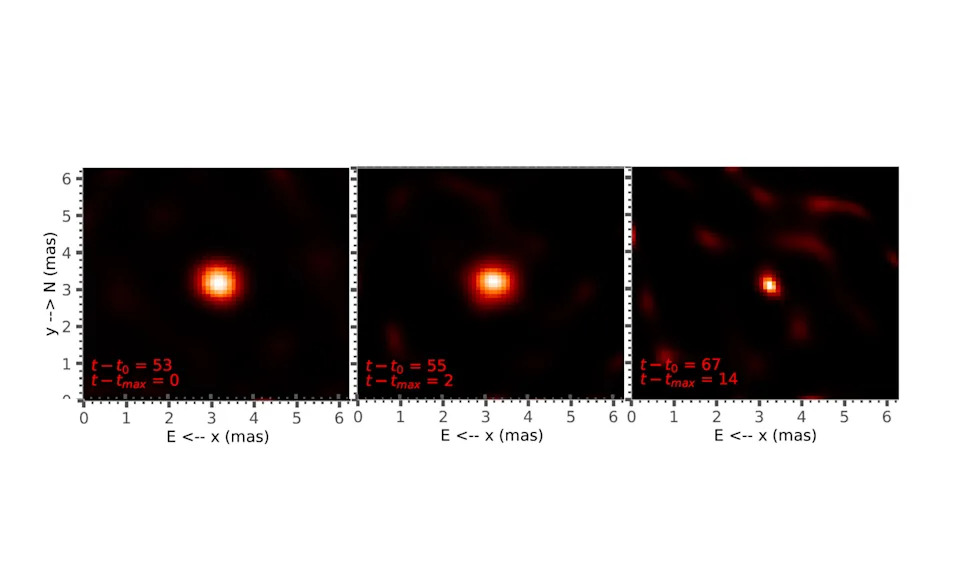

The imaging resolved complex behavior in the ejected material. Instead of a single, symmetric blast, the observations show:

- Multiple outflows: material expelled in different directions and at different speeds.

- Delayed ejections: some material lingers near the system and expands more slowly, implying a multi-stage ejection process rather than an instantaneous explosion.

- Bipolar structure in some cases, with fast material streaming along one axis and slower material moving perpendicular to it.

Two Novae, Two Different Timelines

The paper focuses on two novae from 2021. Nova Herculis 2021 erupted in June 2021, reached peak visible brightness within about 16 hours, and faded significantly within a day. By contrast, Nova Cassiopeiae 2021, discovered in March 2021, brightened over two days, then stalled for a couple of weeks before reaching a final brightness peak roughly 53 days after discovery.

"People have imagined for a long time that novae are kind of like these big nuclear bombs that all of a sudden go off," Chomiuk said. "Our images show the mass loss can take much longer and occur in multiple phases." When material is ejected it can reach enormous speeds — on the order of 10 million miles per hour — but the timing and geometry of those flows vary between systems.

Why This Matters

Resolving the timing and geometry of nova ejections helps scientists understand the physics of surface nuclear reactions, mass transfer in binary systems, and how these events contribute to the chemical enrichment of the galaxy. The observations refine models of how material is launched from accreting white dwarfs and highlight the need for rapid, high-resolution follow-up when bright novae appear.

"These unprecedented images offer direct observational evidence that the mechanisms driving mass ejection from the surfaces of accreting white dwarfs are not as simple as previously thought," Chomiuk and Monnier write in their paper in Nature Astronomy.

Contact: Keith Matheny at kmatheny@freepress.com.

Originally published in the Detroit Free Press: "U‑M, MSU researchers team up to capture best views of exploding stars."