Icebergs are ancient, mostly freshwater masses that conceal about 90% of their bulk underwater and can span thousands of miles as they drift. They preserve air bubbles that record past climates, display vivid colors from ice structure and inclusions, and can roll, hollow out, or release nutrient-rich meltwater. Regions like Iceberg Alley draw seasonal crowds, while organizations such as the International Ice Patrol (IIP) monitor bergs to protect ships.

14 Fascinating Facts About Icebergs — Ancient Giants of the Sea

14 Fascinating Facts About Icebergs

Icebergs are among the most dramatic and informative features of the polar seas. These drifting ice giants are not only visually striking but also carry records of Earths past climate, influence marine ecosystems, and pose real hazards to navigation. Below are 14 well-researched facts that reveal their science, beauty, and risks.

Most of an iceberg is hidden. About 90% of an iceberg's mass sits below the surface because ice is less dense than seawater. That submerged bulk explains the expression "tip of the iceberg."

Underwater hazards are extensive. Even smaller bergs can extend hundreds of feet beneath the surface, making them dangerous to vessels that only see the exposed portion.

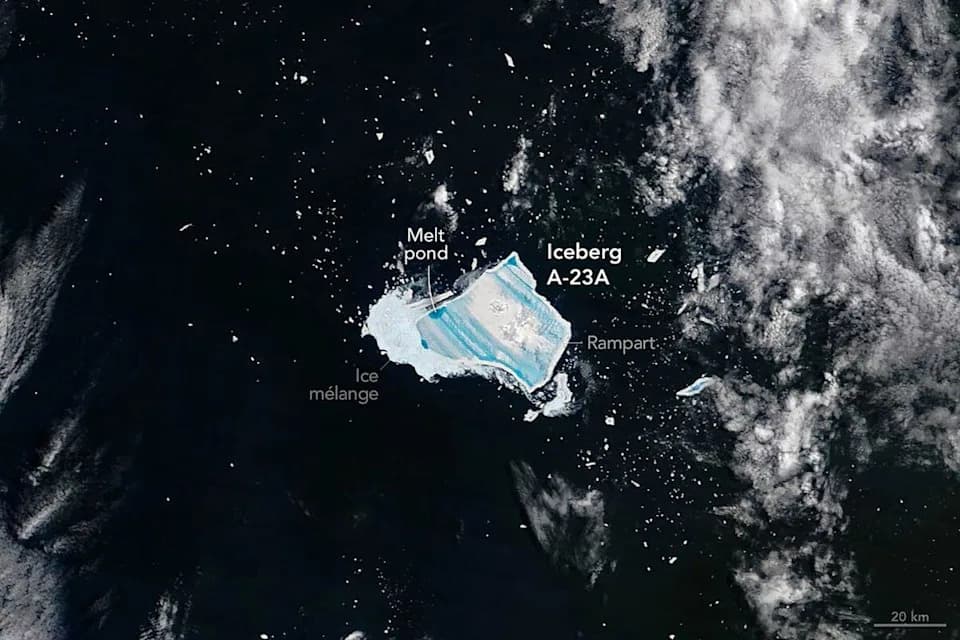

Some icebergs are enormous. The largest recorded iceberg, B-15, calved from Antarctica in 2000 and initially covered about 4,200 square miles, roughly the size of a small US state. Such bergs can be tracked from space and take decades to fully melt.

Icebergs are mostly freshwater. They form when glaciers or ice shelves fracture, so the ice is compacted freshwater, not sea ice. This has inspired proposals to tow bergs as freshwater sources, but practical and environmental challenges remain significant.

Colors tell a story. While many icebergs appear white, dense ice can look vividly blue because it absorbs longer light wavelengths. Green tints often come from algae or mineral inclusions, and layered or striped patterns reflect different formation histories.

They preserve ancient air and climate data. Glacial ice can be tens of thousands of years old. Tiny trapped air bubbles act as time capsules that allow scientists to reconstruct past temperatures and atmospheric gas concentrations.

Iceberg Alley draws the eye. Off Newfoundland's coast, "Iceberg Alley" sees hundreds of bergs drift south from Greenland each year, creating a spectacular seasonal sight and complicating navigation in the region.

Icebergs can roll or flip. Uneven melting or changes in buoyancy can destabilize an iceberg, causing it to roll and reveal newly exposed bases with striking colors and textures. Such events also create waves and additional hazards nearby.

Polar differences in form. Arctic icebergs are often smaller and irregular because they calve from mountain glaciers. Antarctic bergs commonly calve from vast ice shelves and can be tabular, with broad, flat tops and mile-scale dimensions.

Currents and winds steer their journeys. Ocean currents, winds, and tides determine iceberg drift. Tracking these movements helps researchers learn about ocean circulation and predict hazards for shipping.

Melting makes sound. As trapped air escapes while an iceberg melts, it can produce fizzing or popping sounds sometimes called "bergy seltzer." Scientists use these acoustic clues to study melting rates and underwater ice dynamics.

Seasonality affects calving. Spring and early summer often bring peak calving and iceberg numbers in many regions, driven by seasonal warming that increases glacier discharge into the sea.

Hollows and caverns can form inside. Meltwater channels can carve tunnels and caverns within bergs. These features are visually stunning but unstable and dangerous for anyone venturing into them.

Historical impact and monitoring. The iceberg that struck the Titanic likely formed over decades or centuries before drifting into a busy North Atlantic lane. After the disaster, the International Ice Patrol was established in 1914 to monitor ice and warn ships. Today the IIP uses satellites, aircraft, and modeling to keep shipping safer.

Additional note: As icebergs melt they can also release nutrients such as iron into surrounding waters, which may stimulate local biological productivity and influence marine ecosystems.

Help us improve.