RNA — not just DNA — plays a central role in defining cell identity by controlling when, where and how genes are expressed. Only about 2% of the genome codes for proteins; much of the rest is transcribed into regulatory noncoding RNAs. The human epitranscriptome includes over 50 chemical RNA modifications that are dynamic and responsive to cellular state, and altered RNA marks (especially on tRNAs) have been linked to cancer, chemotherapy resistance and neurological and developmental disorders. Scientists propose a Human RNome Project to map RNAs and their modifications across healthy and diseased cells to drive discoveries and new treatments.

RNA Holds the Genome’s Dark Matter — Scientists Are Sequencing It To Illuminate Health and Disease

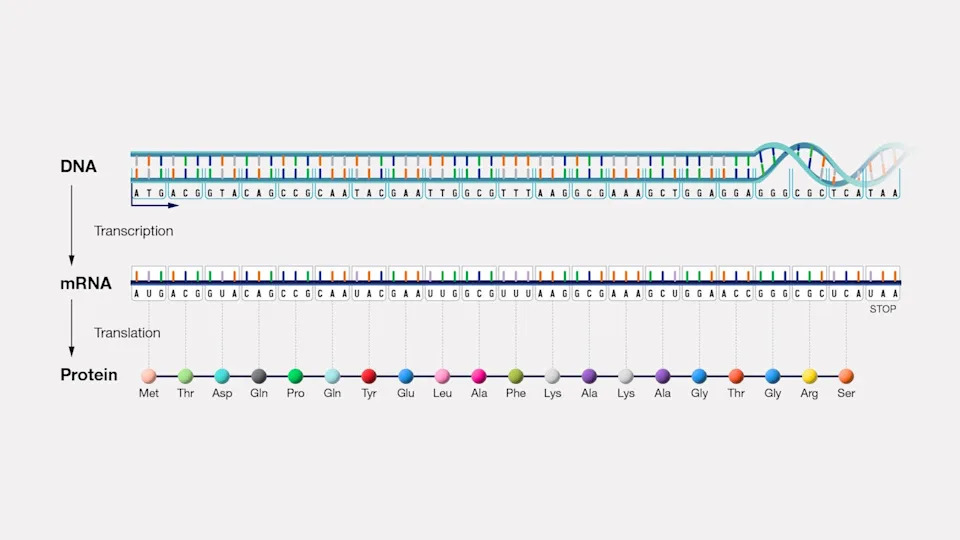

Although the DNA sequence shared by the cells in your eyes, kidneys, brain and toes is essentially the same, those cells behave very differently. Researchers increasingly recognize that many defining features of cell identity arise not from DNA alone but from a close relative: RNA.

RNA: More Than a Messenger

For decades RNA was thought to be a simple intermediary that carries instructions from DNA to the protein-making machinery. Yet only about 2% of the human genome encodes proteins. Much of the remaining “dark matter” is transcribed into noncoding RNAs that regulate gene activity in space and time, helping determine which genes are switched on or off in each cell.

The Epitranscriptome: Dynamic Chemical Marks

Many RNAs are chemically modified after they are made. These RNA modifications — collectively called the epitranscriptome — are discrete chemical groups added to RNA that change how information flows inside the cell. Unlike many DNA epigenetic marks, most RNA modifications are not stably inherited between generations but instead reflect a cell’s current state, making them highly dynamic regulators of cellular behavior.

Researchers have identified more than 50 distinct RNA chemical modifications in human cells. These marks can alter RNA stability, folding, localization and the efficiency or fidelity of protein production, allowing cells to respond rapidly to stress and other changing conditions.

tRNA Modifications and Disease

Work from our laboratory and collaborators has revealed that certain transfer RNAs (tRNAs) — which deliver amino acids to the ribosome during protein synthesis — carry increased or altered modifications in disease states. Abnormal tRNA modification patterns can be drivers of cancer, contribute to chemotherapy resistance, and are implicated in developmental and neurological disorders.

Why a Human RNome Project?

RNA is chemically less stable and structurally more diverse than DNA, and until recently there were fewer tools to study it comprehensively. To catalog RNAs and their modifications across cell types and disease states, researchers are proposing an effort on the scale of the Human Genome Project: the Human RNome Project. The goal is to produce comprehensive maps of the RNome and epitranscriptome to accelerate discovery and the development of diagnostics and therapies.

Key technical challenges remain, including sequencing methods that can detect multiple modifications on the same RNA molecule. Advances in technology, however, have already fueled an “RNA Renaissance,” placing RNA at the center of new vaccines, therapeutics and basic biology.

The Road Ahead

Comprehensive RNome maps could reveal new biological mechanisms, highlight biomarkers for disease, and identify novel therapeutic targets. With global collaboration and improved sequencing tools that read RNA chemistry as well as sequence, the regulatory "dark matter" of the genome may soon illuminate many aspects of human health and disease.

This article is adapted from The Conversation. It was written by Thomas Begley and Marlene Belfort, University at Albany, State University of New York.

Disclosures: Thomas Begley receives funding from the NIH. Marlene Belfort reports no relevant commercial conflicts beyond her academic appointment.

Help us improve.