The Dilley Immigration Processing Center in South Texas has been described by detained families, lawyers and court filings as prisonlike: constant surveillance, crowded dorms, inadequate food, limited schooling and reportedly cursory medical care. Two confirmed measles cases have heightened public-health concerns inside the facility, which court monitors say processed roughly 1,800 children between April and December and held about 345 in December. Advocates also report officials pressured parents to abandon immigration claims and note many detained children are U.S. residents apprehended away from the border.

Children Describe Nightmares, Inedible Food and Little Schooling at Dilley Immigration Center

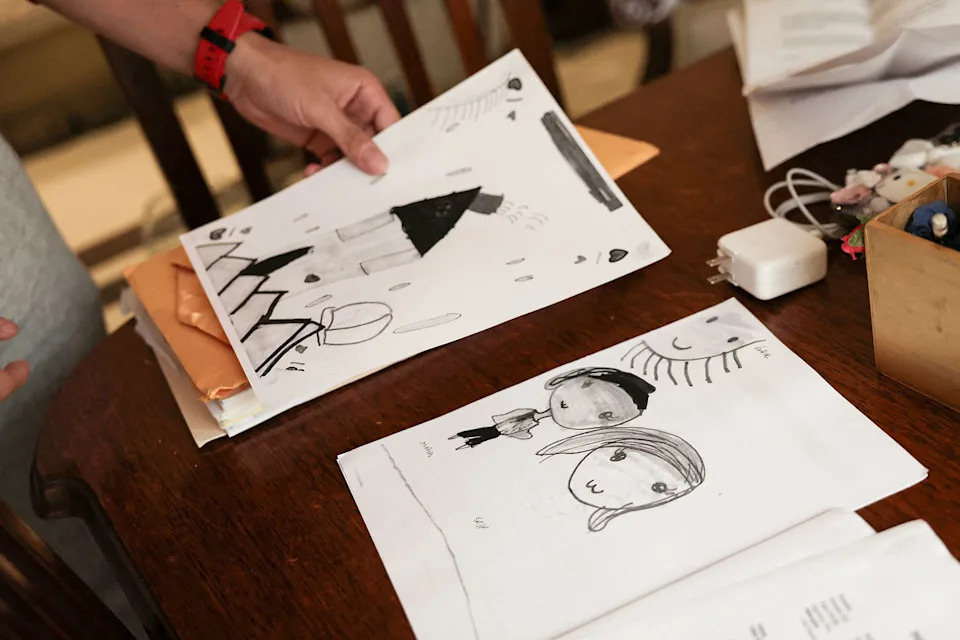

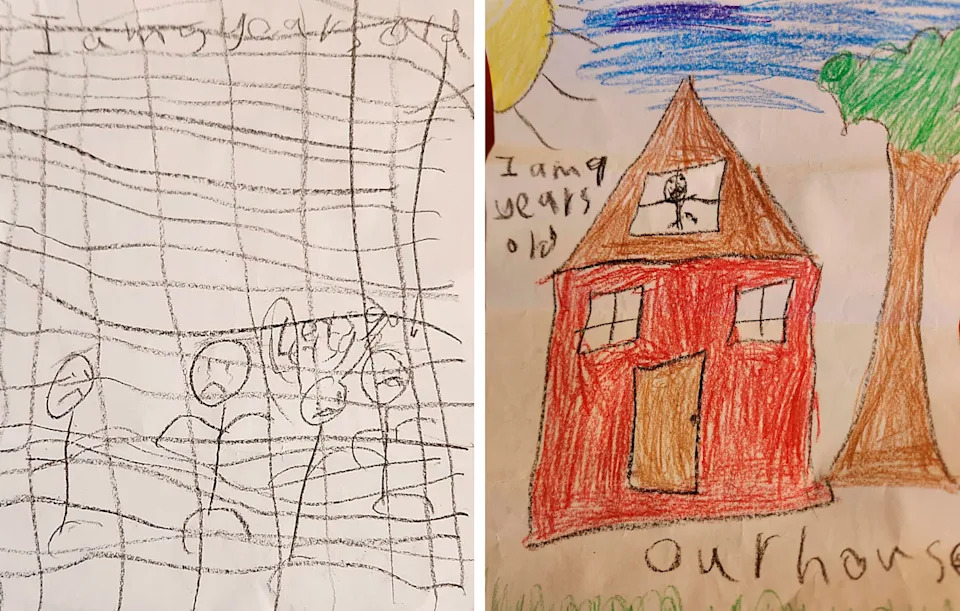

Before arriving at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center in South Texas last fall, Kelly Vargas said her 6-year-old daughter, Maria, was thriving: she loved school, drew in the afternoons and played with her cat. Within days of being detained at the sprawling facility—where guards patrol corridors and lights remain on at night—Vargas said her daughter began to unravel, experiencing bedwetting, panic, sleep disturbances and a loss of appetite.

Accounts From Families and Lawyers

Interviews with detained parents, lawyers and dozens of sworn declarations portray Dilley as a prisonlike facility where children have reportedly endured contaminated or inappropriate meals, limited schooling and cursory medical attention. The facility came into national focus after a widely circulated photo showed 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos entering federal custody; his fearful expression and subsequent illness mirror many accounts from other detained families, lawyers say.

Health And Safety Concerns

Advocates and medical experts have raised alarm after health officials confirmed two measles cases among people detained at Dilley, warning that a highly contagious disease in a crowded setting with young and sometimes medically vulnerable children is an acute public-health concern. Lawyers representing families say they have had difficulty obtaining clear information from the Department of Homeland Security about containment steps or detainee vaccination status.

Conditions Described

Families and court filings describe constant surveillance, rigid schedules, overnight bed checks and crowded dorm-style sleeping areas with limited privacy. Parents report children regressing emotionally and developmentally—experiencing nightmares, refusal to eat, weight loss and, in some cases, injuries or prolonged illness that families say received insufficient medical attention.

“It is a prison where we are keeping children as young as 1 year old,” said Elora Mukherjee, director of Columbia Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic.

Food, Schooling And Medical Care

Court filings allege meals that are greasy, heavily seasoned or inappropriate for infants and preschoolers; some parents reported finding mold or worms in food. Education appears minimal—often limited to about an hour of instruction a day and largely consisting of worksheets—while overcrowding can leave some children without any instruction. Families also report delayed or cursory medical care even when children show troubling symptoms.

Numbers And Administration

Court-appointed monitors estimate roughly 1,800 children passed through Dilley between April and December after the government resumed large-scale family detention in April. About 345 children were reportedly being held there with parents in December. The privately run facility is operated under contract by CoreCivic; the contract is reported to be worth about $180 million annually. Many of the children now detained are U.S. residents who were apprehended away from the border—at homes, schools, courthouses or routine check-ins.

Legal And Ethical Stakes

Advocates say detention is being used to pressure families to abandon asylum or visa claims; lawyers report repeated warnings from officials implying separation or deportation if parents did not "cooperate". The Trump administration has also sought to revisit the Flores Settlement Agreement, a decades-old legal settlement that guarantees basic protections for immigrant children in federal custody—protections lawyers say are being violated at Dilley.

Personal Impact

Vargas said her family ultimately accepted deportation after nearly two months at Dilley. She says her daughter still suffers vision problems, headaches and anxiety triggered by the experience; even the sight of a police officer makes the child tense. Other families and attorneys describe prolonged psychological and developmental harm among detained children.

Note: The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to detailed questions about Dilley for the reporting summarized here. CoreCivic referred inquiries to DHS and said it prioritizes the health and safety of those in its care.

Help us improve.