Teachers across states and countries report more students arriving without basic academic and life skills, including weak reading/writing readiness, poor time management and limited practical abilities. Young children increasingly show sleep and feeding challenges, while many students rely heavily on technology for simple tasks. Educators urge a return to fundamentals—consistent expectations, routines at home and stable curricula that allow time to master basics.

Teachers Report Growing Gaps In Students' Basic Academic And Life Skills

Across the U.S. and beyond, teachers are raising consistent concerns: an increasing number of students arrive at school without foundational academic abilities, practical life skills or independent learning habits. Educators — many speaking anonymously — describe children who struggle with reading and writing readiness, time management, handwriting and basic self-care. They also point to broader issues such as irregular sleep, rigid eating behaviors and heavy reliance on technology.

What Teachers Are Observing

Respondents from a variety of grades and regions reported similar patterns in their classrooms:

- Poor reading and writing readiness: Several teachers said students enter upper-elementary grades still "learning to read" rather than "reading to learn."

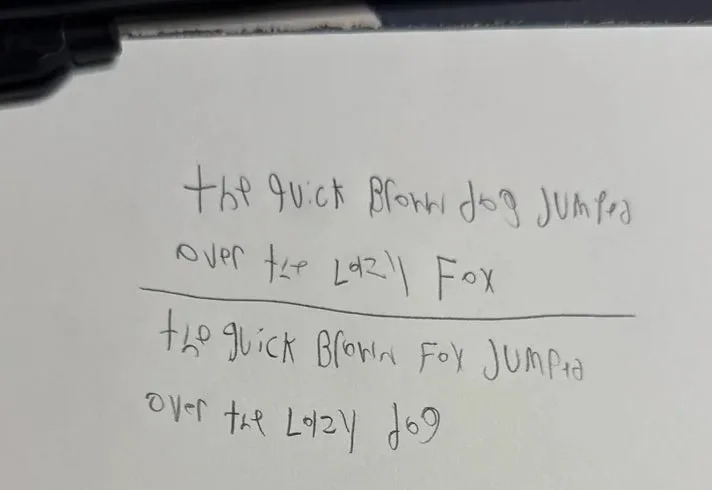

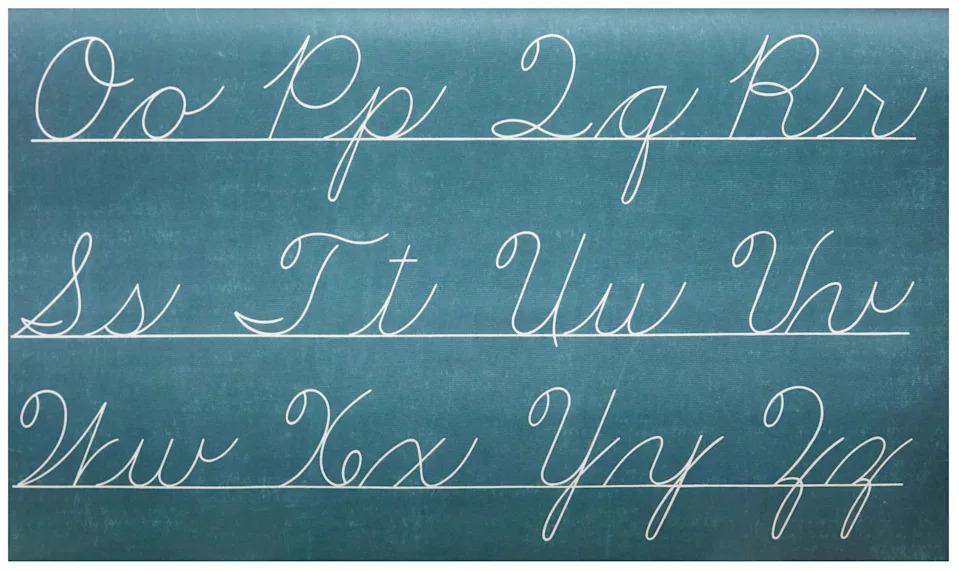

- Weak practical skills: Many students have trouble with handwriting, using simple classroom tools (glue sticks, scissors), winding headphone cords or reading analog clocks.

- Time-management and independent-work deficits: Teachers described students who struggle to follow multi-step assignments, summarize texts or complete work without constant prompting.

- Sleep and feeding concerns in young children: Multiple respondents noted more preschoolers with sleep disturbances or highly selective, rigid eating habits than in past decades.

- Overreliance on technology: Some students know touchpads and Chromebooks but lack experience with basic physical devices (for example, a standalone computer mouse) or offline problem solving.

- Social and emotional skills: Educators reported increasing immaturity, impatience, lower frustration tolerance and difficulty tolerating boredom.

Representative Voices

“Manners are often a thing of the past. Everything is scheduled for kids non-stop, so there is no time for imaginative play or what to do when they’re bored. Students come to my classroom barely able to read — more like learning to read, when third grade should be about reading to learn.” — Anonymous, Washington State

“How do you expect them to sign their names on legal documents? In basic print like a 6‑year‑old?! They have no idea how to work a problem or answer a question by themselves because of ‘group cooperative learning.’” — Anonymous, California

“Administrators and policymakers want quick results without allowing time to teach basic concepts. Stop changing programs every two years. Go back to common-sense teaching: fundamentals first, then build on them.” — Anonymous, 30‑year educator

“I have more 2–5‑year‑olds who don’t sleep through the night than those who do. They need to be rocked or held and demand snacks or stories at 3 a.m. I wonder what the long-term consequences will be.” — Anonymous, Canada

Common Themes And Suggested Remedies

Teachers repeatedly pointed to home and policy factors that may contribute to these trends: excessive scheduling of children's time, increased screen exposure, reduced free imaginative play, and low expectations for age-appropriate responsibilities. Many recommend:

- Re-centering instruction on fundamentals—phonics, handwriting practice, arithmetic fluency—and allowing sufficient time to master them.

- Reducing frequent, short-lived curriculum changes that demand repeated teacher training and distract from classroom instruction.

- Encouraging families and caregivers to set routines (bedtime, chores, reading aloud) and give children age-appropriate responsibilities.

- Balancing technology use with hands-on activities that build fine-motor, attention and problem-solving skills.

Note: The responses have been edited for length and clarity. Contributors remained anonymous in the original reporting; this article synthesizes recurring observations from multiple teachers across regions.

Help us improve.