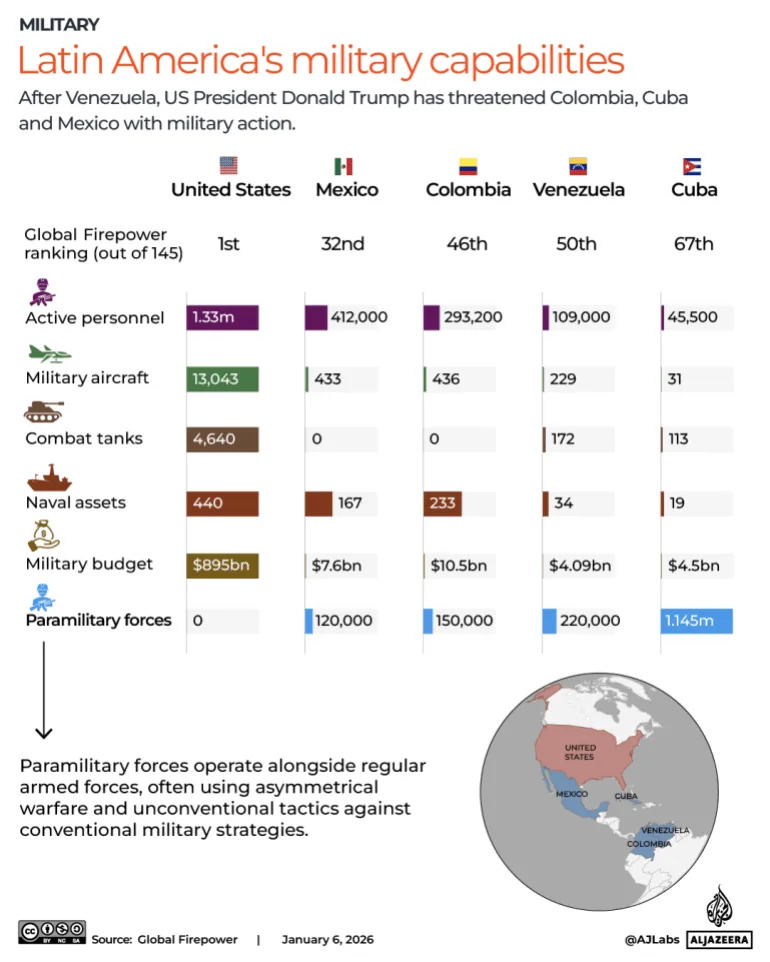

This article assesses the military balance between the United States and Latin American states following reports of a major US strike on Venezuela and heightened threats toward Colombia, Cuba and Mexico. It finds the US retains overwhelming conventional superiority—including a $895bn defence budget in 2025—while many regional actors rely on paramilitary and irregular forces that complicate interventions. Historical US involvement in the region frames current mistrust and strategic calculations.

Latin America vs. US Military Power: Conventional Gaps and the Rise of Paramilitary Forces

Over the weekend, reports described a major US military operation targeting Venezuela and the reported capture of President Nicolás Maduro, a dramatic escalation that reverberated across the region. Washington’s subsequent public threats against Colombia, Cuba and Mexico — framed as efforts to combat drug trafficking and protect US interests — have revived longstanding tensions over American intervention in Latin America.

Conventional Military Balance

The United States maintains by far the world’s most capable conventional military. In 2025 the US defence budget stood at approximately $895 billion—roughly 3.1% of GDP—and remains larger than the combined defence spending of the next ten biggest military spenders. In a conventional interstate conflict involving air, naval and armoured forces, the US retains overwhelming superiority.

According to Global Firepower’s 2025 rankings, Brazil fields the region’s strongest conventional military, ranked 11th globally. Other regional rankings include Mexico (32nd), Colombia (46th), Venezuela (50th) and Cuba (67th). On metrics such as active personnel, combat aircraft, tanks, naval assets and defence budgets, these countries are substantially outmatched by the United States.

Paramilitary And Irregular Forces: A Different Calculator

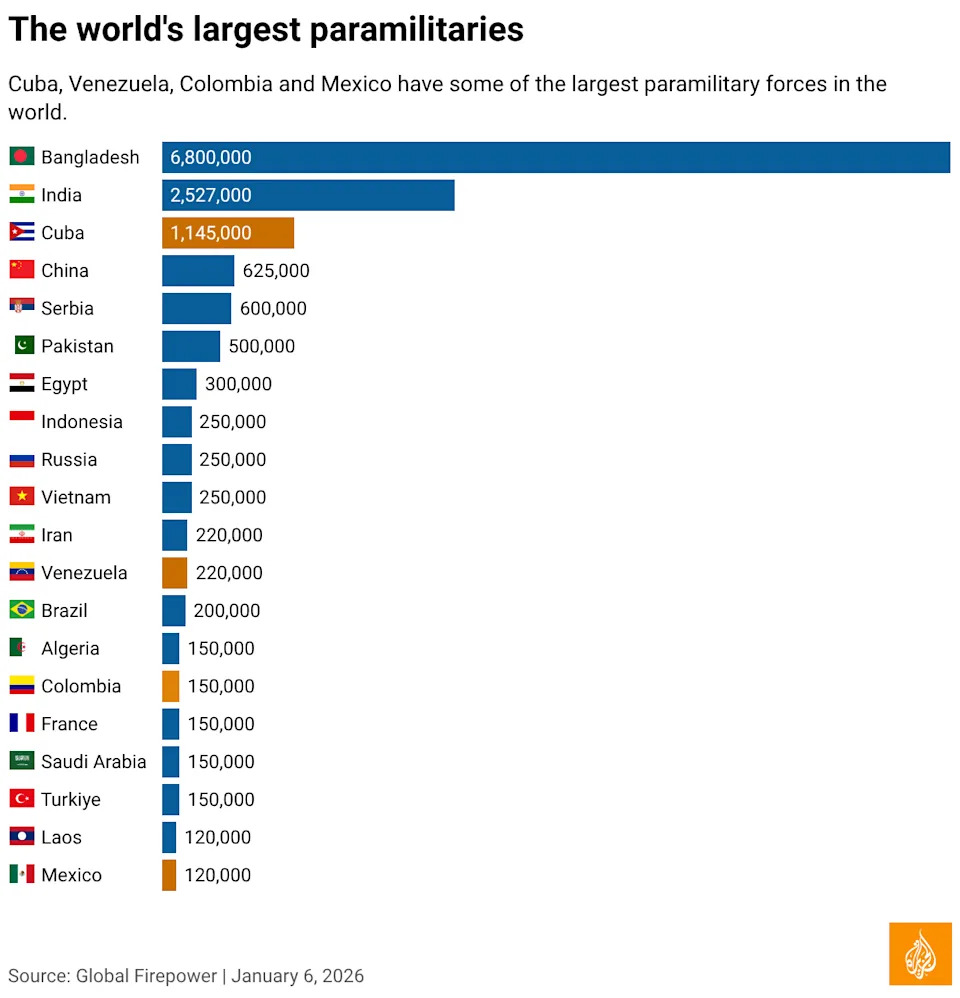

Where some Latin American states and non-state actors can claim comparative strength is in paramilitary, irregular and hybrid capabilities. These actors—ranging from state-organised militias to criminal armed groups—operate alongside or outside formal militaries and frequently use asymmetric tactics that complicate conventional military planning.

Global Firepower estimates Cuba’s paramilitary forces, including state-run militias and neighbourhood defence committees, at more than 1.14 million members; the Territorial Troops Militia acts as a civilian reserve to support the regular armed forces in crises. In Venezuela, pro-government armed civilian groups known as “colectivos” have been accused of political enforcement and intimidation; while not formally part of the military, they are widely believed to operate with state tolerance or backing during periods of unrest.

Colombia’s security landscape was shaped by right-wing paramilitaries that emerged in the 1980s to fight left-wing insurgents. Although many groups were officially demobilised in the 2000s, some reconstituted as criminal or neo‑paramilitary organisations and remain active, especially in rural areas. Early counter‑insurgency efforts in the country were influenced by US advisers during the Cold War.

In Mexico, powerful drug cartels such as the Zetas—originating in part from former soldiers—possess military-grade weapons and territorial control that frequently outmatch local law enforcement. This reality has driven greater use of the Mexican military in domestic security roles.

What This Means For Regional Security

Paramilitary and irregular forces do not negate the US advantage in conventional warfare, but they do alter the calculus of intervention. Asymmetric tactics, local knowledge, urban insurgency capabilities and popular mobilisation raise the political, human and operational costs of any foreign intervention, complicating the strategic picture for Washington and regional governments alike.

Context matters: Historical memories of US involvement—from the Banana Wars through covert Cold War operations—continue to shape regional perceptions and diplomacy. One high‑profile modern example is the 1989 US operation in Panama (Operation Just Cause), aimed at removing General Manuel Noriega.

Ultimately, while Latin American militaries are outclassed in conventional terms, a patchwork of state and non‑state armed actors gives the region unique defensive and destabilising potential. Policymakers assessing future crises will need to balance military capability with political legitimacy, local dynamics and the high costs of asymmetric conflict.

Help us improve.