Researchers at Johns Hopkins used 3-mm lab-grown brain organoids derived from donors' blood and skin cells to model prefrontal cortex neurons and record their activity. Machine-learning analysis detected distinct electrophysiological signatures that classified organoid origin with 83% accuracy, rising to 92% after electrical stimulation. The findings suggest potential biological markers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and point to organoids as a future platform for drug testing, though significant validation in real human brains is still required.

Lab-Grown “Mini-Brains” Reveal Hidden Neural Signatures of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

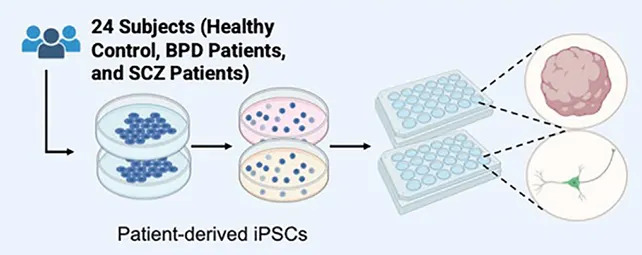

Researchers have used lab-grown brain organoids—often called "mini-brains"—to detect distinct patterns of neural activity linked to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Developed by a team led at Johns Hopkins University and published in APL Bioengineering, the study points toward objective biological markers that could one day complement clinical diagnosis and help screen therapies in patient-derived tissue.

What the team did

The pea-sized organoids (about 3 millimetres across) were engineered from donors' blood and skin cells to produce neural cell types characteristic of the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in planning, decision-making and higher cognitive functions. Mounted on microchips and recorded with multiple sensors, these organoids were analyzed with machine-learning algorithms trained to detect patterns of neuronal communication.

Key findings

The researchers found distinct electrophysiological signatures that differentiated organoids derived from people with schizophrenia, people with bipolar disorder and people without psychiatric diagnoses. Using these signatures, machine-learning models identified the source of each organoid with 83% accuracy. When organoids were given controlled electrical stimulation, classification accuracy rose to 92%, suggesting the differences become more pronounced when neural circuits are actively engaged.

"Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are very hard to diagnose because no particular part of the brain goes off," said biomedical engineer Annie Kathuria of Johns Hopkins University. "No specific enzymes are going off like in Parkinson's... but at least molecularly we can check what goes wrong when we are making these brains in a dish."

Limitations and next steps

While promising, organoids remain far simpler than intact human brains: they lack full brain architecture, vascularization and the sensory and developmental inputs present in living people. The authors emphasize the need to validate whether the electrophysiological patterns observed in organoids correspond to signals in patients' actual brains. Future work aims to expand sample sizes, refine classification models, and explore using organoids as platforms for testing drug responses and dosing strategies tailored to patient-derived tissue.

Why this matters

Today, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are diagnosed primarily through clinical assessment of symptoms. Objective biological markers could reduce misdiagnosis, speed treatment selection, and create new opportunities to screen therapies in human-derived neural tissue. Although clinical translation will require substantial validation, this study offers an important proof of principle that disease-related neural activity can be detected in patient-derived mini-brains.

Help us improve.