Greenland, inhabited for over 4,000 years by Inuit peoples, blends strong Indigenous traditions with Danish institutions. Its economy centers on fishing and Danish subsidies while new airports and tourism expand access. Rapid warming and potential mineral wealth create scientific interest, geopolitical attention and intense local debate about environmental and health impacts. Many Greenlanders favor greater autonomy, even as external powers assert strategic interest.

Life on Greenland: Culture, Climate and the Geopolitics Behind a Melting Giant

Greenland — the world’s largest island — is a place of deep Indigenous history, striking Arctic landscapes and growing geopolitical attention. Long home to Inuit communities, it now combines traditional ways of life with Danish institutions and an increasingly global spotlight driven by climate change, tourism and resource interests.

History and People

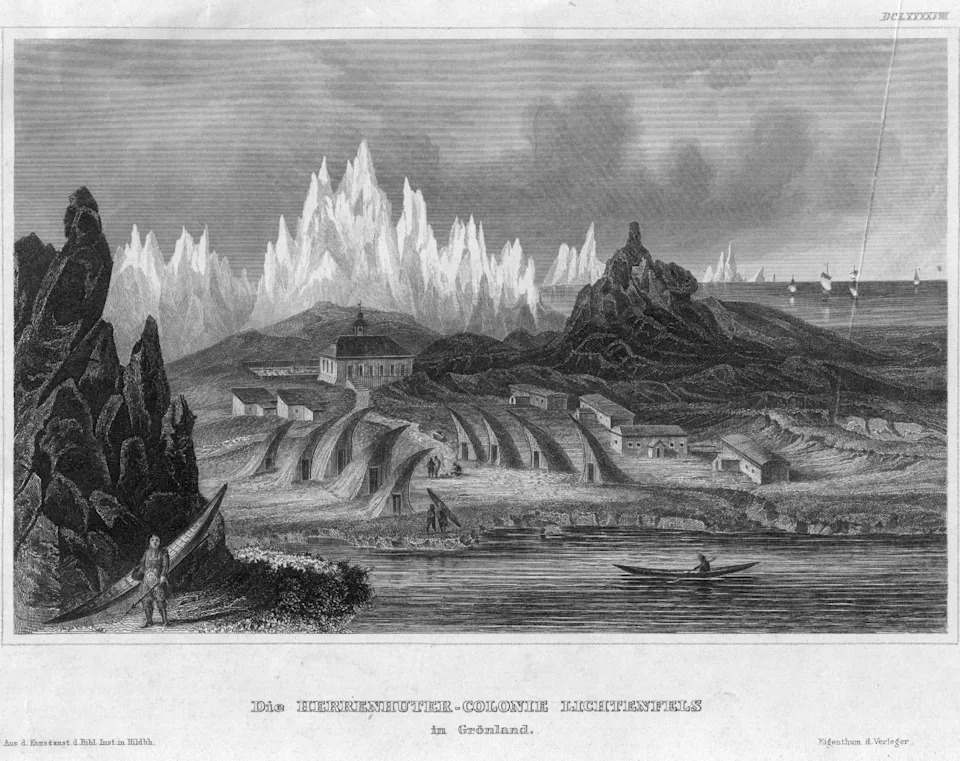

Humans arrived in Greenland more than 4,000 years ago. Early pre-Inuit groups such as the Saqqaq settled coastal areas around 2,500 BCE; today’s Greenlandic Inuit descend largely from the Thule who migrated from Alaska about 1,000 years ago. Norse settlers lived in parts of western Greenland between roughly 985 and 1450 CE; the Norse name "Greenland" appears in European accounts, while in Greenlandic the island is called Kalaallit Nunaat.

Denmark’s presence began in earnest in the 18th century when missionary Hans Egede founded a settlement in present-day Nuuk in 1721. Greenland was a Danish colony until 1953 and gained home rule in 1979. It now governs most domestic affairs through its parliament, the Inatsisartut, while Denmark retains responsibility for defense and foreign policy.

Demographics, Language and Culture

About 56,000 people live in Greenland, most concentrated along coastal towns; that population is smaller than many mid-sized cities elsewhere. Nearly 90% are Inuit or of Inuit descent, with many Greenlanders also having some European ancestry. Kalaallisut (Greenlandic) is the official language; Danish is widely taught and spoken as a second language. Cultural life blends Inuit tradition and Scandinavian influences — from national costumes and carving to Scandinavian-style architecture in larger towns like Nuuk.

Economy and Infrastructure

Fishing remains the backbone of Greenland’s economy, but it does not fully finance public services. Denmark provides an annual subsidy — reported at roughly $511 million — that supports the government budget. Interest in tourism is growing as new international airports open: Nuuk inaugurated an international airport in November 2024, and other hubs such as Ilulissat and Qaqortoq are expanding connectivity, enabling direct flights from destinations like New York in recent months.

Potential mineral wealth (uranium, lithium, gold, rare earths and hydrocarbons) has raised hopes for economic diversification but also fierce local debate about environmental and health risks. Communities such as Narsaq have voiced concerns about proposed uranium projects, reflecting broader caution about large-scale mining’s impact on fragile ecosystems and fisheries.

Climate Change and Science

Greenland is a frontline of global warming. About 80% of the island’s roughly 836,330 square miles is covered by ice and snow, and scientists have documented substantial ice loss: a 2016 study estimated the ice sheet was losing the equivalent of about 110 million Olympic-sized swimming pools of water per year. Thawing permafrost and retreating glaciers are already affecting infrastructure, wildlife behavior and traditional livelihoods. Greenland’s ice also makes it a key site for international scientific research, from ice-core studies to climate monitoring.

Daily Life and Traditions

Daily life varies dramatically between Nuuk — a modern Arctic capital of around 20,000 people — and small settlements where fewer than 100 residents may live much as their ancestors did, relying on hunting, fishing and seasonal knowledge. Transportation in remote areas can mean boats, dog sleds, snowmobiles or helicopters; the Greenland dog remains a valued working breed. Cuisine reflects the environment: local staples include fish, seal, whale and, in southern areas, sheep.

Long polar nights and the midnight sun shape seasonal life and cultural rhythms. The extended darkness of winter has helped foster a strong reading and literary tradition, while music, visual arts and social media influencers are helping preserve and promote Greenlandic culture to broader audiences.

Politics, Sovereignty and Geopolitics

Discussions about Greenland’s future — including greater independence from Denmark — are longstanding. Many Greenlanders support increasing autonomy; a 2008 referendum expanded self-rule, and polling suggests strong interest in full sovereignty, though opinions vary on timing and risks. Recent U.S. political attention, including public comments by former President Donald Trump about acquiring the island and the appointment of a U.S. special envoy, sparked pushback from Denmark and renewed debate about Greenland’s strategic value and the risks of external pressure.

Outlook

Greenland is at an inflection point: climate change is reshaping its environment, new transport links are expanding tourism, and resource prospects are creating both economic opportunity and social tension. For Greenlanders, the central question remains how to balance cultural preservation, environmental stewardship and economic development while determining the island’s political future.

Sources: Reporting and research from BBC, Reuters, The New York Times, The Guardian, AP and academic experts are reflected in this overview.